|

||||||||||

|

Volume 12, Issue 24 ~ June 10-16, 2004

|

||||||||||

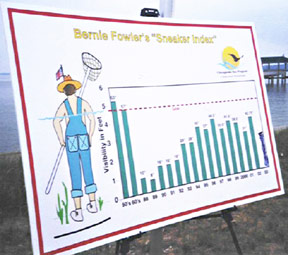

Bernie Fowler leads Bay converts to the water and urges them to walk on in by Sara E. Leeland Will the people on this river Ever see clear water once again? —Tom Wisner June is wade-in Month in Chesapeake country. The season started early on the Patapsco on May 23. Annapolis waded June 5. On June 12 people on the Choptank River, the Lower Potomac River and the Upper Eastern Shore wade. The Chesapeake Bay Environmental leader, on June 19, stages a wade-in at Grasonville. On June 27, it’s wade-day for the Lower Western Shore. In Calvert this weekend, the Patuxent River’s passionate politician, former Maryland Sen. Bernie Fowler, continues the tradition he began 16 years ago, in 1988, with yet another Patuxent River wade-in. This June 13, Bernie plans to shift the emphasis: from simple community education to prodding decisive political action. He’ll challenge all who speak from the podium this year to make clear commitments: what exactly they will do before the 2005 wade-in to bring this river back to health. Some major figures — Gov. Robert Ehrlich, former Gov. Harry Hughes, Senators Barbara Mikulski and Paul Sarbanes, Congressman Steny Hoyer and state Sen. Roy Dyson among them — are expected. So news beyond the usual wade-in photo feature is anticipated. For the pre-wade-in moment: a little perspective. A Near-Failing River If we gave the Patuxent a current health report card grade, it would get a score of 48 out of 100 for a D+, Dr. Bill Dennison of the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science told a session of the Chesapeake Bay Commission in January. Fowler — Bernie as nearly everyone calls him — remembers those waters back when the score was surely closer to a B+, though no one was measuring back then. That was in the late 1920s and ’30s, the era when it’s said that a waterman could spot a crab (or even an eel hole) in the sandy river bottom, looking right through as much as five to eight feet of water. Back then, Warren Denton Company at Broomes Island was packing on ice upward of 300,000 crabs a month and sending them by boat south to Norfolk and north to Baltimore. For lack of crabs, Warren Denton closed three years ago. Crab harvests have fallen to all-time lows. The 2003 Baywide blue crab harvest amounted to only 48 million pounds, or about two-thirds long-term average of 73 million pounds. And that was a year when “modest gains” were made, according to the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment report this month. If you catch an eel in the Patuxent, you need to be careful about eating it. The Maryland Department of Environment has listed a one-eel-meal-a-month advisory for the river’s delicacy, a result of water poisoned by PCBs and pesticides. The near-flunking grade for the Patuxent is especially bad because it follows a recovery in the 1980s, when the river bounced back from the heavy sewage effluent of exploding suburban populations. That dirty water had led Bernie and other Marylanders to sue the state to force better cleanup of all the lightly treated toilet waste. Nineteen-seventy-nine was the magic year. Gov. Harry Hughes became a convert after accompanying Fowler and his band of advocates on the Patuxent for a personal view of the degradation. With Hughes’ leadership from 1979 to 1985, some protections were put in place. He championed the 1984-’85 Critical Areas Law that led to planting shoreline buffers against runoff. In 1985, he fought off intense lobbying from the detergent industry to enact the Maryland Phosphate Detergent Ban. Then in 1990, Maryland legislators upgraded standards for sewage treatment plants. Advanced water treatment plants succeeded in bringing nitrogen down. The river headed back to health. But then things took another turn. Population kept growing, outdoing the effect of lowering pollutants per gallon by the sheer volume of sewage arriving for treatment at the up-river plants. At the 2003 Patuxent wade-in, Bernie Fowler pressed Gov. Robert Ehrlich for action. Ehrlich promised a new round of cleanup for the state’s sewage treatment plants. What we got from the 2004 Maryland Assembly session was the flush tax, which will raise up to $78 million a year by charging home owners $30 a month and businesses on a per-use rate to pay for better sewage treatment. Those millions will pay for upgrades by an “enhanced nutrient removal” method called “nutrient stripping,” which will bring Maryland’s 66 l

In the Patuxent watershed, seven plants are on the list to be upgraded: Western Branch, Bowie, Patuxent, Little Patuxent Parkway, Maryland City and Dorsey Run. Lest you relax, feeling that the cleanup is definitively underway, note that Maryland’s Department of Environment has already announced that the flush tax will bring us only one-third of the way toward the nitrogen pollution removal previously promised for the year 2000. From a wade-in perspective, the flush-tax bill is Ehrlich’s down payment on the promise made at last year’s Patuxent River wade-in. Expect more payments to be called due at the upcoming 2004 Patuxent wade-in. Making a Splash Signs that the 2004 Patuxent wade-in would push even harder for political action showed up as early as October of last year. Bernie Fowler called together a roomful of folks whose names are well-known in the Patuxent watershed. Ralph Eschelman, former director of the Calvert Marine Museum, was there, as was Kent Mountford, ecological historian and a former lead scientist at the EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program. Tom Horton, Chesapeake Bay writer and Sun columnist, and Tom Wisner, the Bay’s folk singer, came. Chesapeake Biological Lab’s ecologists Walter Boynton and Joseph Mihursky, along with lab chief Ken Tenore, signed in, bringing others newer to river concerns. “We need to make a real change in the way society treats the river,” said Mountford, who lives near St. Leonard Creek. “It’s being overwhelmed by people. Nothing in the last 30 years has done more than temporarily interrupt the river’s decline.” Their agenda was how to use 1979’s lobbying success as a model for a new push for strong political action in 2004, kicking it off at the Patuxent wade-in as a catalyst. Here’s what they planed: First, they’d invite a group of politically powerful people to learn on a river cruise before the wade-in, with senior scientist on board to explain both problems and potential solutions. Second, each speaker at the wade-in podium would be asked to make a clear commitment to action in the coming year. Then, the group would join hands to walk into the river together. It’s hard, planners reckoned, to go back on a promise sealed by wet feet. From the Patuxent River, whose entire watershed lies in Maryland, begins a new push to bring back the Bay. Can This River Be Saved? “A major thing to realize is that cleaning up the Patuxent is doable,” Boynton — who will brief the dignitaries — told Bay Weekly. He’s so good at translating the complex science into short-and-sweet issues that he’s wrapped it all up in three neat packages. The path from our toilets and sinks through sewage treatment plants to the river is still the biggest problem. In 2005, Boynton says, the Environmental Protection Agency will set maximum levels for nitrogen and phosphorus in the Patuxent. That pronouncement will give Maryland a scientific basis for capping those nutrients in sewage flow. Then, if population keeps growing, the effluent will have to get cleaner and cleaner to keep the total levels in line. This will not be a one-time fix. Dirty runoff water from farms and paved surfaces is the second pollution poisoning the Patuxent and the Bay. Cover crops will control farm runoff. Maryland’s new flush tax is helping to pay for such crops. Thirty percent of the money it brings in will be used to provide financial assistance to farmers for cover crops. But such voluntary measures have been advocated since the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s. Cleaning up the Patuxent may require mandating them. Working with urban and suburban runoff will demand new planning from architects and construction firms along with retrofitting paved surfaces. How does Boynton think that can be accomplished? “Remember how the three important words in real estate are location, location, location?” Boynton asks. “Folks in Florida who are doing innovative things with runoff say the three big words are retention, retention, retention.” Forested areas, rain gardens and runoff collection ponds work to retain pollutant-filled water from rushing through storm drains into the rivers. Acid rain is the third threat to Patuxent water quality. Half of that acid does come from westward places, says Boynton. “But half is generated right here,” he adds, “by electric plants and automobiles.” Cleaning up the Patuxent may head Maryland further in the direction of requiring cleaner cars that go farther per gallon of fuel with lower emissions. As for power plants, Calvert Countians have been staring for years at the plumes of smoke rising from the Chalk Point electric plant on the Prince George’s County shore of the Patuxent, then wafting down-river and across their county with the winds. Added to those emissions is pollution from the Morgantown plant in Charles County, the Potomac River plant in Alexandria, and Dickerson in western Montgomery County — all operated by Mirant Corporation and together the region’s single largest source of air pollution from mercury, nitrogen and sulfur dioxide.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was headed in the direction of clamping down on polluting power-plant emissions under New Source Review of the Clean Air Act, which required coal-fired power plants and many factories to install the latest clean air technology when expanding their operations. But the Bush administration last year cancelled implementation of the new rule under political pressure from utilities and manufacturers. So Mirant Corporation has no incentive to do better. Instead of cleaning up, last November it announced its intention to buy “clean credits” from power companies outside the region — a form of trading EPA allows to keep U.S. emissions at a steady level. But clean credits won’t push emissions down in the Patuxent region. Now is clearly the time to push for cleaning those and other smokestacks. If Bernie Fowler says we must save the Patuxent River, and Walter Boynton says that we can do it, surely Maryland politicians will decisively fund sewage treatment, demand better storm water retention and cleaner air. That, at least, is the hope of those planning Patuxent wade-in 2004. Political Will Begins with Wet Feet In real-life, predicting political actions is as risky as predicting horse races. Howard Ernst offered the first analysis of the political situation around the Chesapeake and its rivers in his 2003 book Chesapeake Bay Blues. “Public policy,” he wrote, “tends to follow the course of least resistance. Political actors support economic growth and prosperity.” But what kind of growth and prosperity? From the moment that English colonists set foot in the land they called Maryland, economic growth and prosperity depended on freely taking the land and waters of this place along with its fish and fowl, birds and mammals. Thanksgiving was expressed to God, and colonists worried about the silting in of the rivers, but the political action to protect the waters never balanced economic growth and prosperity How do we change old habits to new, sustainable ones? Clearly, politicians need support from citizens who grasp the doability of Walter Boynton’s outline of solutions and will join in demanding public policies that protect our rivers — and thus the Bay. Letters and e-mails are a start. But nothing gets you motivated for action like experiencing connection to our rivers. A public ritual, like the river wade-ins happening across the region, helps develop that connection and the commitment as a community. The Ritual of Wading In Artist and folk singer Tom Wisner, who helped Bernie Fowler shape the first river wade-in, knows that art and ritual shape politics. Looking back, Wisner remembers being deeply struck by the simple and refreshingly clear image of Bernie’s description of a test for a healthy river: Being able to wade in shoulder deep and still see his toes at the bottom of the river. He wrote a poem about it (see sidebar), which Tom Horton printed in his Baltimore Sun column in 1986, then again in 1987’s book, Bay Country, which won the John Burroughs Medal. Wisner had waded into the Severn River with Piscataway medicine man Turkey Tayac. Tayac explained that he wade into the brackish, salty tidal waters at least once a year to cleanse himself of burdens carried over from the previous year.

So he encouraged Bernie to move beyond words in his sneaker test to an actual wade-in. As Wisner tells the story, that first year a small group waded in. He and Bernie were joined by innovative schoolteacher Betty Brady and a few of her students, by Walter Boynton from the Chesapeake Biological Lab, his family and some friends. Bernie carried a crab net in one hand, reliving the experience of searching for crabs on the river bottom. In following years, Bernie invited his political friends, especially fellow Democrats. Soon National Geographic and other media featured his wade-in as an unusual happening. It’s a powerful ritual. Hand in hand and in silence, people walk into the river fully clothed, experiencing the chill of early-summer water on their feet, legs, thighs and tummies (depending on their height and how clear the water is). June’s the month when the water is warm enough to do it — and often cold enough to wake you up. For some waders, the important point is when Bernie declares a stop because he can no longer see the white of his tennis shoes through the water. That’s “Bernie’s measure,” the inches of depth as compared to previous wade-ins. But some people come back year after year because a wade-in is more than a measuring test. It is a community experience of our connection to this river. Like it or not, it forces us to ask: How are we connected to the murk and the hidden pesticides in the river? How can I help clean it up? When we get clear about that, the river will get clearer. Today, for many people the Patuxent is just the water that flows under highway bridges at Waysons Corner, Benedict or Solomons. There are other ways of seeing. Former Navy captain Richard ‘Dusty’ Rhoades, who directed the flight school at the Patuxent River Naval Base, puts it this way: “When I’d fly over the Patuxent River, what I’d see is the incredible land and water interface. Flying up there, you work your way to destinations in terms of points of land and water, the string of islands from Hooper to Tangier, the long, beautiful loops of the Wicomico on the Eastern Shore. Coming home, the PAX River navy base is framed by the Patuxent and the bridge at Solomons. “Whether you see them everyday or not, the rivers of this place are the engines that drive life here. And the Patuxent is the river we belong to. It gives its name to the base and to so much else of what is here.” Dusty takes his vision seriously. At the wade-in June 13, he’s making a community commitment to the Patuxent’s health.

The Patuxent River wade-in was not meant for large crowds. Parking in a possibly muddy field is limited, as is the amount of cover from the tent. It’s likely that if the wading line got too long, the ritual would disintegrate. If you’re a passionate Patuxent River person, follow Calvert’s Broomes Island Road and watch for the wade-in signs. But more important is to wade into your creek, river or stretch of the Bay. Following Bernie’s success, there are now wade-ins on the Choptank, the Upper, Lower and the Middle Potomac, the Patapsco, the South River, the Magothy River as well as on the Upper and Lower Western and Eastern Chesapeake Shores. Even better, create informal wade-ins of your own. Silence during the wade-in is important: It leaves inner space for awareness of the river. Knowing a little about your creek or river is helpful, too, as is making and sharing of a commitment of your own. “I have a dream,” says Tom Wisner, “that the Bay Program will take some NBC reporters up over the Chesapeake on wade-in day 2025. What he hopes they’ll see all over the Bay, is “thousands of folk wading in, making their commitments to their rivers.” For More Information: Check Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources web site for times and dates: www.dnr.state.md.us/bay/tribstart/wadein. The state of our sewage treatment makes it wise to run a check of contamination levels. Maryland Department of Environment’s web site lists both fish-health advisories and sewage system overflows: www.mde. md.us. In Anne Arundel County, the Department of Health samples water for enterococci, bacteria signaling wastes in recreational waters: www.aahealth.org; 410-222-7999. |

||||||||||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. |