|

|||||||||

|

Volume 12, Issue 26 ~ June 24-30, 2004

|

|||||||||

Visitor center rises to link past and future by Becky Bartlett Hutchison By next summer’s end, you could be strolling down the street of a small port town as laughing children race each other to the waterfront. A carpenter sharpens his tools for the new workday. The smell of spices and tobacco rise from the dock, mingling in the humid morning air as sailors load heavy barrels of tobacco onto the deck of a merchant ship. Ordinary life in Maryland’s London resumes with gardens, houses, workshops, a tavern, a port and a sailing ship reviving the town, which flourished hundreds of years ago, from 1684 to 1760. In the years after 1760, the mostly wooden town decayed. All that remained by our time was a two-story brick structure that had, for 150 years, served as the county poorhouse. Outside the county-owned property, a one-and-a-half-story frame building survived although much changed. For all anybody knew, London had never existed in Maryland. In the 1970s, surprising finds suggested an old port town. In the 1990s, the town was discovered in archaeological digs by the county’s Lost Towns Project. Written records described activities in and around London Town, but excavations proved the exact location and layout of the town. “Archaeology is what gives London Town its authenticity,” said Donna Ware, director of the property. In this new century, London gets closer every day to the town founded in 1683 as a tobacco port. If you haven’t been there lately, prepare yourself to walk back into history. Lest time travel disorient you, by next year you’ll stop first in the thoroughly 21st century Visitor Center, which is the biggest news in London this year.

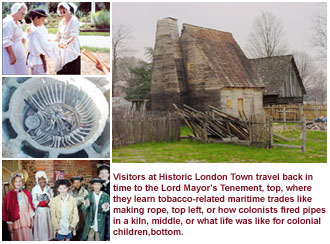

Today, you can return in time to the town’s earliest days (circa 1684 to 1710). Over the last two years, the Lord Mayor’s Tenement has risen in the same post holes where it stood three centuries ago. In 2002, a crew — London Town volunteers and the Annapolis Woodworkers Guild directed by master housewright Russell Steele — lifted the frame into place. Raising and building were done just as they would have been in the 1680s and ’90s. Now all but the clay and sand lining inside the chimney is finished. It’s a small building with few furnishings, where costumed interpreters explain domestic life, which back then varied dramatically depending on your class: from freemen and women to indentured servants to slaves. During special events, food is prepared and cooked over the large hearth in the manner of the earliest residents. Behind the tenement within the roughly-fenced African American Garden, interpreters tend herbs and vegetables typically grown by London Town slaves. Just a few steps away from the garden and tenement, you leap forward in time to London Town’s most prosperous era (1720-1760) as a transportation and business center. In the tobacco barn and yard, visitors learn tobacco-related maritime trades by making rope, pressing tobacco tightly into barrels and lifting heavy barrels with block and tackle. A bit farther down the road toward the William Brown House, beside a gully that was once Scott Street, greenhouse-like digloos — a word created by the Lost Towns Project staff combining dig and igloo — cover and protect the remains of the original Rumney’s Tavern (circa 1724) and its cellar. Once archaeological excavations end, perhaps five years hence, the tavern will open again, for what town can thrive without a tavern? The William Brown House — an imposing Georgian structure facing Scott Street and one of only two surviving buildings from the old town — stands for London Town’s declining years (1748-1823). Here, interpreters explain how new tobacco inspection laws destroyed the town, leading to its abandonment, and how Mr. Brown’s continued misfortunes mirrored the town’s fate. He lost both his home and tavern and his prosperity.  Alongside Rumney’s Tavern and the William Brown House, the large gully that was once busy Scott Street slopes down to the South River. Scott Street, which ended near the ferry crossing, was a major north-south transportation route in the Mid-Atlantic colonies. Along the waterfront, you may one day ride on a recreated ferry, board a visiting merchant ship or walk through a shipyard while listening to stories of London as it used to be. Alongside Rumney’s Tavern and the William Brown House, the large gully that was once busy Scott Street slopes down to the South River. Scott Street, which ended near the ferry crossing, was a major north-south transportation route in the Mid-Atlantic colonies. Along the waterfront, you may one day ride on a recreated ferry, board a visiting merchant ship or walk through a shipyard while listening to stories of London as it used to be.In with the New The biggest building in the new town, however, will be nothing William Brown and his contemporaries of 1750 would have imagined. Sitting at the edge of the reconstructed village, the new two-building 12,000-square-foot London Town Visitor Center and Museum will look like a bigger, though distinctly modern, relative of the Lord Mayor’s Tenement. Inside and below ground, the center will be definitely designed for the 21st century. It, too, stands on an old foundation: the Woodland Beach wastewater plant abandoned in 1987. Recycling the underground plant reduces impact on the nearby waterfront and will help keep construction costs down, since a building foundation is already in place. The Baltimore firm of Cho Benn Holback and Associates, Inc., won the prestigious 2001 AIA Baltimore Design Award for best practice in environmental planning of its adaptive reuse. At ground level, an environmentally friendly plaza will hold six inches of soil and plants to catch storm runoff and to give the underground museum a living, green roof. “It’s a very expressive building that will improve the quality of visitors’ experience, said Gordon P. Smith, chairman of London Town Foundation, the non-profit that operates the 10-acre property. Anne Arundel County, which owns the historic site, is paying $2 million for the new center. Rounding out the cool $5.35 million cost of the project is $750,000 from a 1998 Maryland bond bill and $2.6 million in Transportation Enhancement Funds from the Maryland Department of Transportation.

The orientation center is like nothing colonial town residents would’ve seen, but its exhibits will help us see them better. Into the Future The new London Town will boost the fortunes of 21st century Anne Arundel County, Smith says, as it offers one more place in this region for tourists to visit, stay a bit longer, and spend more tourism dollars. Historic London Town and Gardens is already a premier site in the Four Rivers Heritage Area, a historic tourism consortium encompassing Annapolis, London Town and Southern Anne Arundel County. London Town is also a site in the National Park Service’s Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network. When the new London Town Visitor Center and Museum opens in late summer 2005, the town will again become an important destination for local travelers, as well as for tourists in the Chesapeake Bay and greater Mid-Atlantic regions. Thus London Town will come full circle, from a colonial travel destination to a modern travel destination — after a hiatus of only 250 years.

|

|||||||||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. |