|

|||||||||||||||

|

Volume 13, Issue 8 ~ February 24 - March 2, 2005

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

True Tales from the Hood by Sandra Olivetti Martin The not-so-toughs of HBO’s The Wire talk about making good Stringer Bell hit the bare floor hard, dead as his dream of turning corner drug money into high-rise wealth.

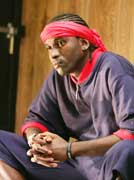

ayed a miscellaneous hustler in Wire episode 33. “The HBO broadcast is so large, so many people see it,” he said. “They know you on The Wire.” “Why you gotta go and f— with the program?” That was Brandon Fobbs’ big line. Highlighted on the screen at the beginning of episode 29 as that show’s theme-setting quote, it also explains much of the action of The Wire over its three seasons and, in particular, over the just-ended third season’s 12 episodes. Fruit, Fobbs’ character in seven episodes of the past season, is a working man. Says Fobbs of Fruit: “I work one of the corners for the big, bad new drug dealer, Marlo, and I recruit boys to work for me. I keep up the facade of being hard, and I keep my corner profitable.” In episode 29, the natural laws of Fruit’s universe slip, and he reacts much as you or I would if our jobs were shipped overseas. Stricken by the futility of chasing street-level drug dealers off their corners day after day, a police precinct captain has reached outside the box and the law. He herds the dealers into two free-trade zones, where they’re allowed to do business without police interference — so long as they keep out of the rest of his precinct. The new order shakes Fruit’s tree. “Look: We grind, and y’all try to stop it,” he says to a policeman. “That’s how we do. Why you got to go and f— with the program?” Drugs, sex, violence, street language larded with four-letter words and an ethic of self-serving cynicism that cuts across lines of class, race, gender, education and achievement to flourish on both sides of the law: That’s the culture of The Wire. Created by David Simon, formerly a Baltimore Sun crime reporter, and Ed Burns, a former police officer, it’s the third in a prime-time series of gritty cops-and-robber stories set in Baltimore’s mean streets, with occasional excursions to Annapolis and Chesapeake Bay. First was Homicide, which evolved from Simon’s crime beat. The 600-page book became a televison series that ran from 1993 to 1999 on NBC. Next Simon collaborated with Burns on The Corner, which focused on the robbers and drug dealers. The Corner was adapted to television as an HBO miniseries. Th

In The Wire, all that meanness convenes in Baltimore. “It’s really negative,” says a matron in this black history audience. She says her pleasure at “seeing brothers working” is tempered by the image they portray. Her comment plunges the real-life actors and screen-time toughs into a defense that’s been around as long as art has reflected life in its mirror. “There’s a lot negative in reality TV,” agrees Glover, whose deep voice rumbles like stereo speakers set to high bass. “We do not live in fairytale world,” explains another Wire actor, Melvin Jackson Jr., who plays Bernard. “We have such a high population of drug users, and it’s not just Baltimore,” says Brandon Larkins, another of the young locals whose future has been shaped by The Wire. “You’ve got a lot of single moms and guys with nowhere to go, and a lot of brothers going to jail,” adds Glover, who says he comes from the D.C. version of the same world. “I’m a product of Oak Hill, with a single-parent mom and all we did was drugs. I never was like a car thief, but when you’re in the hood, you’re in the hood. “

In The Wire, Larkins is on the other side of the law from Glover, who does murder, and the gangs. In real life, Larkins is a church-going public school teacher as well as an actor, and he knows that art not only reflects life but also affects it. “I’m sure we can do better in the African American community,” he says. “Through The Corner and working with the NAACP [the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which has its headquarters in Baltimore] we got a lot of funding for drug programs and to help single parents.” So, says Fobbs, “As far as showing the city in a bad light, you need to see what’s wrong to understand it and make a difference.” Concludes Glover, “The Wire is negative, but it’s positive, too.” Doing Better The Wire’s young actors are part of its positive side. For each of them, landing a part on the series was a dream come true. For many, like Brandan Tate, it had first been a dream deferred. “The first season I was an extra and did like three episodes,” says Baltimorean Tate, who likes to get a laugh. “They liked how I looked and everything. So they asked me to audition for second season, and I auditioned 10 or 12 times. I wished I’d hurry up and get on the show. So what I did, I was telling people I was on the show before I was on the show. “The third season, they called me again, Next thing I knew, I got a part. My character, Sapper, was on two episodes and they ended up writing him in for the rest of the season. He’ll be back,” says Tate — though the future of the show remains uncertain. Fobbs, too, was getting frustrated with dead-end auditions. By the time he got called for third-season auditions, he’d moved to California.

“I was doing my Hollywood shuffle, when the casting director called me for another part on The Wire, one that would be a major returning role,” Fobbs recalls. “So I said Is it worth it? And he said, Yeah, if you get it. “I had no money,” Fobbs continues. “So I got my father to fly me back. This time I was a little fed up, so I adopted something from another character that I wrote about in college. He didn’t have any lips and his eyes were beat up and everything. He had a face like that [he screws up his face]. I didn’t want to give them the lips part, I figured that was too much, but I did the lazy eye part, and they loved me.” Fobbs didn’t get the big part, the upstart dealer Marlo, but his character, Fruit, not only got an episode-heading quote; he also provokes a major turn for a key character in the series. Glover’s role came easier. “After the first audition they called me back and I read like four more parts,” he says. “I was coming from Houston on my way getting on the plane, and HBO came up [on the phone] and says Are you sitting down? “I’m thinking, Why do I need to sit down? “And he says, You landed Slim Charles. “I was so happy and I couldn’t even sit down the whole flight,” Glover says. Charles had a name, but Glover made his fame as the stoic henchman who is gang leader and right-hand man to star Avon Barksdale. “My character was only supposed to be brief,” Glover says. “But I got with the cast members, the writers and everybody and they liked my presence. I was cool. I just quoted my passages, quoted my lines and studied a lot, and here I am, Slim Charles.” Now, the young actors are parlaying their experience on The Wire into new work that keeps them on screen rather than on corners.

Drive and presence have meant other film roles for Glover. Big G. — or Genghis, as he’s known in his own right — has roles in two more films to be shot this spring and summer: Levi’s Gift and The Trap. He’s also lead singer in a D.C. go-go band (go-go is a percussive urban music that originated in the District), and does a weekly Sunday night radio show, the Ghetto Prince on WPGC 95.5 FM. Funnyman Tate, too, got into The Trap. “I’m trying to be like Samuel Jackson, in five or six movies at a time,” he said. From appearing in a single episode of The Wire, Baltimorean Howard G got measurable leverage. In episode 25, he played the police desk sergeant to whom that season’s fallen hustler, a longshoreman named Nick, surrendered. He spoke six lines. “The Wire has boosted my career,” says the 37-year-old stand-up comedian. “Lots of people saw me and remember me.” Howard, alias Grandma, G’s fame is high these days on account of the car insurance commercial Kiss My Bumper. Additional jobs are commercials and theater. “I’m working regularly,” he says, “making the rounds” through Philadelphia, Virginia, D.C, New Jersey, and New York. Brandon Fobbs’ evaluation of his experience with The Wire holds true for all these aspiring actors, even Glover. “The Wire was my biggest credit,” he says. “It opened me up to a lot of people and sealed my credentials as a pro.” Hustling and Grinding The Wire’s cops and robbers are doing better than the corner boys with nowhere to go. But like their brothers, “We’re all hustlers,” Larkins says, “and we grind.” By which he means that behind scenes, the actor’s life is an act of faith supported by hard work. “Basically after every production is finished,” he explains, “you’ve got to consider yourself unemployed. You cannot ride on your past accomplishments. You have to keep going.” Larkins’ act of faith is literal. “That’s where prayer comes in,” he explains of how he rides out the uncertainty of a career that’s a string of temporary assignments. “I just ask God for guidance. I might be blessed to get another opportunity for an audition. I might be blessed to get a job in another TV production.” Used to stepping out on faith, Larkins got a solider foundation from his work in The Wire. He advanced from a drug-dealing extra in season two to an officer of the law with a regular place on the show in season three “I was able to work, take it really serious and become a member of the Screen Actors Guild, which is very hard, especially for African Americans,” he said. Fobbs, too, puts his fate in God’s hands. “I view Samuel Jackson as one of the tools God used to tell me acting was what I want to do. I watched Pulp Fiction in 1993, and I said to myself, That’s like what I want to do. “From there it’s been an uphill battle, but God supports me,” Fobbs says, explaining how he lives after giving up corporate America’s regular salary — the marketing major graduated to a job with Frito-Lay — for the actor’s life.

“You’ve got to have it inside you. You’ve got to really want something,” Jackson says. “I’m the type of person if you tell me I can’t do something, I’m going to do it anyway, ’cause that’s just how you’ve got to be.” Faith and determination only go so far, the actors agree. Luck plays a part, but hard work is their biggest ally. Just how hard the work is awes some of these young men “You know, I didn’t want to do any work,” says Tate of his first high school acting class. “But it seemed I got a talent for it, and I really got into these scenes. My teacher says, You know, you’re pretty good. You ever consider a career? “I’m like, an actor?” Now, he says, he’s suffering for taking his teacher’s suggestion. “Just make sure that’s what you want to be,” he advises, “because it’s a very hard position to break into. It’s cutthroat, and there’s a lot of effort to it.” The work’s not only hard; the hours are long, says Glover. “Your morning is like 4am. You’re not working; you’re still just waiting around. You might be there all night. Then you may have call time at 6am.” Still, the young actors of The Wire count themselves among the lucky ones. “For every one person that has a job, hundreds of people want to take that job,” Fobbs says. “You’re not going to put up with this unless you have a passion for it, because it’s not an easy job. But nobody’s forcing you to be here,” Larkins says. “We’re happy to be in there, and we’re very humble right now.” Like Glover, Larkins had a role in the Disney movie Annapolis. He’s also writing music and acting in industrial shorts. Still, he says, “None of us can afford to quit our day jobs. So I’m back in the public schools as a teacher.” |

||||||||||||||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. |