Life in the Extreme

The fittest of sailors and the finest of yachts are whittled away by pounding winds, intense labor and extreme weather in the round-the-world Volvo Ocean Race

by Kat Bennett

The whole boat is shuddering and shaking as we crash through one wave to the next, all the winches and blocks are screaming and cracking like cannon fire under the load. Water poured down the deck and into the hatches, so we bailed out every half an hour or so to avoid turning the leeward side of the boat into a swimming pool.

–Simon Fisher: navigator aboard ABN AMRO TWO

Icy winds called williwaws sweep violently down from the land. Floating fields of ice and submerged icebergs slash through hulls like icy knives. Numbing cold stiffens the brain and fumbles hands and feet. These are the diabolical conditions endured by the Volvo Ocean Race fleet as they speed through the fourth leg of the most prestigious and treacherous yacht race in the world, from Wellington, New Zealand, to Rio de Janeiro.

The race motto, Life in the Extreme, is an earned title.

This race has been extreme from its beginning. A first round-the-world race in 1970 ended disastrously when only a single boat finished. The rest gave up, capsized or sunk. One despondent sailor committed suicide. Sponsors evaporated, reluctant to be associated with such destruction.

But the challenge intrigued the British Royal Navy, which promised support and space for such a race. On September 8, 1973, 17 60-foot sailboats pulled up to the starting line in Portsmouth Harbour, England, to follow a grueling course along the old trade routes of the clipper ships.

Thus began the Whitbread Around the World Race, which every four years assembles a fleet for the hardest, toughest and most coveted competition in the racing world.

Whitbread, the name from 1973 to 1997, was borrowed from sponsoring Whitbread PLC, the 250-year-old brewery since diversified into one of the world’s largest suppliers of food, drink and recreational products, including Pizza Hut and T.G.I. Fridays. Swedish Volvo Car Corporation and AB Volvo took over sponsorship in 2001.

In no other race do sailors sail as fast or as wildly.

Paying Neptune’s Toll

Paying Neptune’s Toll

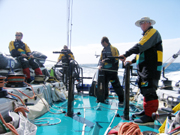

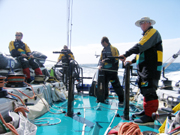

The fittest of sailors and the finest of yachts are whittled away by pounding winds, intense labor and extreme weather as the ships wind through icebergs, gales and stagnant, sweltering doldrums.

Conditions on board are rough. Space is limited and amenities nonexistent. “When you try to get dressed,” Paul Cayard, captain of Pirates of the Caribbean writes, “it is all you can do to not get thrown down and smash your face into the leeward hull 15 feet below. The noise is like being inside a 55-gallon drum and being dragged down a cobble stone road.”

Discomfort is the smallest price sailors and yachts pay to race around the world.

Not every body, or every boat, makes it back. In the very first race in 1973, 17 boats started out and only 14 arrived back, the others sunken or broken. Three sailors in that harrowing race were lost in the Southern Ocean. One man was flung over during a strong gale. Another disappeared, “harness and all,” during heavy weather. The third fell overboard.

In 1985 the Whitbread was clouded once again by another loss of life when two men were swept overboard in the Southern Ocean. Radio beacons aided in their recovery. Yet one of those swept overboard, Anthony Philips, died and was buried at sea.

Back to the Present: 2005-2006

This year in Vigo, Spain, millions turned out to cheer the boats from a new starting point. Seven yachts entered, each with an international crew of seasoned sailors eager to see if they have what it takes to sail the Volvo Ocean Race. Of the 77 sailors, a single woman raced in this year’s Volvo; Adrienne Cahalan, 40, raced with Brasil 1 in only the first leg.

Neither money nor fame is the motive here. It is the rush that sheer speed brings, the thrill of sailing the finest race yachts of all time, the honor of sailing the most grueling race course in the world and the chance of beating the best yacht racers in the world.

In 2006, six countries — Australia, Brazil, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United States — vie for the Volvo trophy. Yet this is not a competition between nationalities. Crews, designers and builders are multinational. Each ship boasts the best sail racers from around the world including Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, France, Great Britain, Canada and Tasmania in addition to the racing countries.

There is plenty at stake. Considered the Rolex of racing, each Volvo 70 costs between $4 and $6 million to design and build. An additional $20 million is spent to man and operate each boat. Each has two crews; an onshore team for communication and repairs as well as the racing crew. Advertising and marketing costs may add another $20 million.

While crews come for the challenge, sponsors come for the media attention. The Volvo Ocean Race represents better branding than Formula-1 auto racing. Every point on the course generates millions for the local economies; Wellington, New Zealand, reported that more than $62 million flowed in while racers, fans and advertisers covered that leg of the race.

Designing to Win

Early races were come-one, come-all events with boats of all sizes, shapes, manufacturers and ages. In 1973, 17 boats 32 to 80 feet in length assembled for the first Whitbread. One entry was a private yacht built in 1936; another was a cutter so new the crew finished construction as they raced.

In 1985 a completely new class of boat, the 80-foot Maxi, made its appearance. Designed specifically to race in the Whitbread, this new design was used by seven of the 15 entries. None won that year, but a new era in racing had begun.

The Whitbread 60 appeared in 1993. That race featured only two styles of boat: the Maxi and the new W60. Endeavor, a Maxi, was the fastest yacht, but the new W60s were the wave of the future. Fast and maneuverable, they provided fierce, close competition and exhilarating sport. By 1997, only the W60s competed. When Volvo assumed sponsorship in 2001, these boats were renamed the Volvo 60s.

To intensify competition for 2005-2006, race officials wanted the most extreme class of race boat and created specifications for the Volvo Open 70. Carrying 62 percent more downwind sail and weighing 4,400 pounds less than the Volvo 60s, these new yachts added stability with a canting keel that could tilt up to 40 degrees out to the windward side.

Yacht designers from around the world competed for the honor of creating each of this race’s seven boats. Only three were chosen: the new kid, Don Jones for Australia’s Brunel; the innovator, Juan Kouyomdjian for the twin Dutch boats ABN AMRO ONE and TWO; and proven classicist, Annapolitan Bruce Farr, for Ericsson, Brasil-1, Pirates of the Caribbean and Movistar.

Founded in 1981, the Annapolis-based Farr Yacht Design, Ltd. has won over 40 world championships with its designs with boats engineered for all-around speed and adaptability. In contrast, Kouyomdjian’s ABN AMRO boats are gamblers maximized for strong winds.

The Yachts

ABM AMRO ONE and ABN AMRO TWO: Netherlands — The key to ABN AMROs’ power is their double rudder, which provides extra control when the boats are heavily heeled over and allows a wider, more efficient hull shape.

Brasil-1: Brazil — Captained by former Olympic gold-medal sailor Torbin Grael, Brasil-1 boasts an outstanding Bruce Farr design with a rounder, more forgiving keel than his other entries.

Movistar: Spain — Designed by Bruce Farr, Movistar went with the single rudder for greater sailing efficiency but replaced the mast with a lighter one so more weight could be added to the keel for stability.

Ericsson: Sweden — Sporting the powerful stern and single high rudder characteristic of Bruce Farr’s designs, Ericsson is very similar to Movistar.

Pirates of the Caribbean: U.S.A. — Also known as The Black Pearl in honor of Disney’s next pirate film, this yacht has a rounded keel and single rudder design similar to Brasil-1.

Brunel: Australia — The most massive of all the entries, Brunel was designed for rigors of the open ocean. She’s had several name changes — Premier Challenge to Sunergy & Friends to Real Estate Brunel to Brunel — and bad luck. This yacht will be shipped to Baltimore within the week to re-start the race on that leg.

Evolving the challenge

After weeks of extreme sailing in 1973’s first race, the first boat’s exultation at crossing the finish line was crushed when the prize was awarded to one of the smallest vessels in the race, the 58-foot sloop Esprit d-Equipe. Until 1997 the races were handicapped. As each boat finished, its time was corrected as if it had been the same length and class as the first boat to finish. That was the last year any boat would win on corrected time. Boats were thereafter designed specifically for this race, created to specification.

In 1999, scoring was changed to increase and vary the competition. Winning came to be based on accumulated points earned for each leg. Mixing leg lengths created sprints as well as marathon runs. The 1999 course of four legs over 26,700 nautical miles was finished in 152 days (corrected to 133 days, 13 hours) by Sayula II, a 65-foot ketch. (A nautical mile, 6,076 feet is measured over the curve of the earth and is longer than a standard land mile, 5,280 feet).

Winning came to be based on accumulated points earned for each leg. Mixing leg lengths created sprints as well as marathon runs. The 1999 course of four legs over 26,700 nautical miles was finished in 152 days (corrected to 133 days, 13 hours) by Sayula II, a 65-foot ketch. (A nautical mile, 6,076 feet is measured over the curve of the earth and is longer than a standard land mile, 5,280 feet).

Today’s race — nine legs spread over 32,700 nautical miles — will require more than 180 days to complete even while new speed records are broken again and again. This year, scoring and excitement are refined further with the addition of in-port races and checkpoints. The checkpoints, or gates, act as race markers, steering the fleet along a similar route and away from exceptional dangers such as icebergs and providing more opportunities to collect points.

With the new overall points scoring system, a captain can withdraw from one leg, repair a boat and re-enter the race at another leg. Losing a single leg no longer means losing the race.

Sponsors have responded by making greater investments than ever before, creating the best racing yachts ever seen. Keep track of the overall scores, as points keep adding up, at the Volvo Ocean Race website www.volvooceanrace.org. Each boat also supports its own website with design details, personal crew stats and sailing games.

Leg 1

Vigo, Spain, to Cape Town, South Africa: 6,400 nautical miles

Barely had the 2005-2006 race set off ’round the world when trouble struck. Pirates of the Caribbean’s keel hydraulics failed. Turning back for repairs, the crew dropped the leg and were flown to Cape Town to await the other boats. Two hours later, Movistar, the Spanish entry, put to the coast for a similar problem.

ABN AMRO ONE faced double trouble. First, the yacht broached; then fire broke out. Had the volatile resin of the hull fully ignited, the carbon-wrapped yacht would have turned into an inferno. ABN AMRO TWO was struck by lightning. Despite their troubles, the Dutch twins swept Leg 1, taking first and second positions.

Outdistanced by playful seals in the light air, Brasil-1 suffered an agonizingly slow run into Cape Town for third place. Days before they expected to finish, Ericsson lost control of their canting keel. Determination and seamanship still brought them in fourth in a five-boat leg.

As the boats prepared for the next leg, Adrienne Cahalan, this year’s only woman, was asked to leave Brasil-1. For the first time since 1977, the round-the-world fleet races with an all-male crew.

Leg 2:

Cape Town, South Africa, to Melbourne, Australia: 6,100 nautical miles

Trouble with the canting keel continued to hound the Volvo Seven on Leg 2. This time, Ericsson suffered a broken ram at start and had to withdraw. Instead of racing to Melbourne, the Swedish yacht was shipped there by ocean freight.

Deep in the Southern Ocean, Pirates of the Caribbean discovered a major keel leak. As they hurtled along through the frigid seas, two of the crew hauled a raft inside for a workbench while they cut and welded carbon steel. Their determination earned them fourth place coming into Melbourne.

As the Pirates welded their keel, Brasil-1 was dismasted in the path of a hurricane. Assisted by local fishermen, the badly damaged ship was pulled to shore, then shipped to Melbourne by truck.

Huffing into third place, Movistar placed best of the Farr designs. Yet it was ABN AMRO ONE that led the entire leg despite a torn mainsail, onboard power failure and an injured crewman. ABN AMRO ONE and TWO replayed the first leg, capturing first and second place.

Brunel came in fifth, sailing cautiously under alternate rigging after a lost forestay almost snapped the mast.

Leg 3:

Melbourne, Australia, to Wellington, New Zealand: 1,450 nautical miles

Only six boats set off for Wellington. Brunel remained behind, withdrawn for repairs. Now on route to Baltimore via cargo ship, the Australian will be restarted with the rest of the fleet under a new crew.

With keel troubles again, Ericsson took advantage of a racing rule to suspend racing without withdrawing from the leg, gaining time for repairs and to finish the race without any penalties.

In the closest finish in the history of the race, Movistar swooped into Wellington nine seconds ahead of ABN AMRO ONE. The crew closed a gap of 40 nautical miles by taking advantage of the ABN AMRO boats’ weakness in light airs. Pirates of the Caribbean took third after additional keel repairs. Next came Brasil-1. ABN AMRO TWO slipped in for a tardy fifth, slowed by torn sails and the race’s first serious injury when a crewman was swept down the boat and into a daggerboard.

At Leg 3’s end, special awards honored Andre Fonseca for outstanding bravery. The Brasil-1 sailor dove into freezing water to recover the pieces of the mast and sails. Pirates of the Caribbean’s Justin Clougher earned the Ocean Watch Environmental Award for his descriptions of the bird and sea-life along the route.

Leg 4:

Wellington, New Zealand, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: 6,700 nautical miles

Without Brunel, only six boats braved the wild weather and fierce cold of Cape Horn. This is an extreme place. Waves three times the length of the boats blow up suddenly, battering and slamming the crews as they maneuver over icy decks. Constant sail changes, bitter cold and lack of sleep drain crews, making them even more vulnerable.

The ship is sinking are words that every sailor fears. But modern communications, mechanical pumps and airtight bulkheads kept the men safe despite knee-deep water in the cabin. That’s how Movistar got back on the water. The Chilean navy helped with a temporary repair, so the yacht is sailing steadily yet cautiously toward Rio.

Cape Horn exacted a toll from other boats as well. Ericsson caught fire. As the yacht pitched and rolled with the huge waves, a bank of batteries broke loose, electrifying the entire hull. Skipper Neal McDonald reported that “we were getting shocks from everything, acrid smoke filled the boat and flames were starting to show.”

Pirates of the Caribbean leaked from the rudder again. Even though the water aboard increases with speed, the Pirates are still jockeying for one of the top three positions with ABN AMRO ONE and Brasil-1.

So intense were the waves round the Cape that ABN AMRO TWO reported most its deck stanchions were reduced to bent metal and many of its sails torn. Yet they survived. When the boats arrive in Rio some time this week, no one can gainsay them the right to put one foot up on the mess table, the sailor’s reward for sailing around Cape Horn.

At this point, recurring problems from the new canting keels seem to give the Dutch boats the advantage. But there is still a lot of race to go. Repairs to keel hydraulics seem effective and Pirates, Brasil-1 and Ericsson have closed in on the leaders. The race is tight, and even Movistar is pushing as hard as she can. Winds will be light, and the captains agree that any of the boats could be first to Rio.

This is yacht racing at its finest; keep track of it all online, and look for issue-by-issue updates in Bay Weekly.

Leg 5:

Rio de Janeiro to Baltimore, Maryland: 5,000 nautical miles

The fifth leg runs up along the South American coast and through the Caribbean. Then on to the Sargasso Sea and the Bermuda Triangle, a giant whirlpool of seaweed and still air where becalmed ships have become floating wrecks manned by skeletons. Called the Sea of Lost Ships, it is a place where waterspouts and intense storms build and disappear so quickly they go undetected by weather satellites.

If the yachts survive those hazards, they will follow the Intercoastal Waterway, dodging tankers and fishing trawlers as they make their way to the crab pot marker minefields of the Chesapeake Bay to finish at Baltimore Light, east of Gibson Island.

Parades, regattas and the Baltimore Inner Harbor’s Waterfront Festival provide crews, fans and residents with plenty to see and do, including a Maryland Rio night sponsored by The Ram’s Head.

Leg 5-B:

Baltimore to Annapolis: 400 nautical miles

After a spirited sail from Baltimore, the Volvo 70s arrive at Annapolis City Dock for the Maritime Heritage Festival from May 4 to 7. Concerts, exhibits and boat building are free to the public. Check Bay Weekly for details and updates.

The festival is still looking for volunteers; if you can spare four hours, sign up at http://mdmhf.org/2006/.

Paying Neptune’s Toll

Paying Neptune’s Toll

Winning came to be based on accumulated points earned for each leg. Mixing leg lengths created sprints as well as marathon runs. The 1999 course of four legs over 26,700 nautical miles was finished in 152 days (corrected to 133 days, 13 hours) by Sayula II, a 65-foot ketch. (A nautical mile, 6,076 feet is measured over the curve of the earth and is longer than a standard land mile, 5,280 feet).

Winning came to be based on accumulated points earned for each leg. Mixing leg lengths created sprints as well as marathon runs. The 1999 course of four legs over 26,700 nautical miles was finished in 152 days (corrected to 133 days, 13 hours) by Sayula II, a 65-foot ketch. (A nautical mile, 6,076 feet is measured over the curve of the earth and is longer than a standard land mile, 5,280 feet).