|

|||||

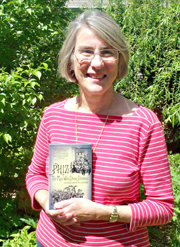

Illuminating a Famous Forefather

|

|

How Phiz Got His NameAfter signing a mere two plates as N.E.M.O., Hablot Knight Browne became Phiz. It can be no coincidence that Dickens had just introduced a character called Fizkin into Pickwick. That, combined with the artist’s gift for etching ‘phizzes’ (faces) and the public craze for physiognomy, are all good reasons for the pseudonym, but Phiz himself remarks: ‘I signed myself as “Nemo” to my first etchings before adopting “Phiz” as my Sobriquet, to harmonise — I suppose — better with Dickens’s “Boz.” –Valerie Lester, Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens |

Phiz was a stranger when Lester first found traces of him in the Victoria and Albert Museum library in London. There she found a book called Phiz: A Memoir, written in 1882 by F.G. Kitton, who knew Phiz’s son, Walter. In the biography, Lester found reproductions of letters Phiz wrote to Walter. Such letters are few and far between, she says, because Phiz burned most of his correspondence. She also learned where Phiz was buried.

So to find her great-great-grandfather’s life, she started with his death. Traveling to Brighton, England, she found his grave.

“I went to this cemetery and found a large, Victorian tombstone with lead lettering. Half the letters were missing, they had fallen off,” Lester reported. “As I watched, one fell off. I took it as a message.”

That sign led Lester to restore the six-foot marble tombstone, which gave her the next clues: She found out her great-great grandmother’s name was Susannah, and the dates that they both died: Phiz in 1882 and his wife in 1902.

Adhering to the Victorian design, Lester rejected replacing the old lead lettering — which didn’t pass the test of time — and instead had a slate panel cut to fit into the original marble headstone. For the job, she hired letterer Helen Mary Skelton, great-niece of famous letterer Eric Gill — who gave us the typeface Gill Sans — to chisel white letters on black slate. Then monumental masons shaped it into the marble panel where the old lead letters had been.

“Restoring the tomb made me feel much closer to him,” Lester said.

Once she touched base with his final resting place — tangible proof of his existence — Lester forged ahead to find him in literature and pictures.

“There had been a lot written about the illustrations and how they related to Dickens’ text,” she said, “but very little biographical matter. What I was interested in was not only his work, but his life.”

With so little written on Phiz, she turned to the author whose name made Phiz’s work famous: Charles Dickens.

At the Dickens Museum in London, she spent a few days going through their files and finding very little. But the museum’s curator told her of a man in Scotland who also claimed to be a descendent of Phiz. Traveling to the Scottish island of Mull, Lester found a distant cousin — another great-great-grandchild — who had Phiz’s desk, but nothing in it.

The Scottish cousin — Gordon Anderson — had yet another clue for Lester.

“He said, ‘You should really get in touch with my sister. She’s a family genealogist, and she’s got lots of information and lives on your side of the Atlantic, Vancouver,’” says Lester. She followed the tip to Canada. There, the sister — Margaret MacKenzie — had photographs, drawings and paintings by Phiz’s children, as well as a few by Phiz himself.

“Through her I learned the names of some of his children,” Lester said. In turn, this Canadian cousin clued Lester in on yet a third cousin in London, Peter Browne.

Hot on the trail, Lester struck gold.

Browne had a genealogist’s dream: a hand-written family history.

“That’s what gave me the leg up,” says Lester of the 1903 history by Englishmen A.S. Bicknell and C.G. Browne. “My book has been dogged by serendipity. Things have fallen into my lap time and again.”

By now she knew the names and important dates of Phiz’s family. And she knew there were more stones to turn over.

The handwritten family history introduced her to more cousins and long-lost family relations, from England to Australia.

“I’m an only child,” Lester said, “[so through my research] I gained a family I never had.”

Finding Fine Lines

|

|

Phiz’s “work is uneven, but absolutely brilliant when it’s good,” as in “Bravo Toro!” in Charles Lever’s Roland Cashel, above. But on a bad day, Lester says, his “illustrations would have much less detail and fewer background sketches, as in “Super-Vision” in Lever’s One of Them, below. |

|

To understand Phiz’s life, Lester immersed herself in Phiz’s world.

“I had to educate myself in Victorian illustration,” said Lester, who took classes in etching to comprehend what Phiz’s work entailed. “I learned just how good he was by applying myself to the same discipline,” she said of work she found labor-intensive and demanding.

This ability to work on a miniature scale was a skill Phiz inherited from his ancestors. Lester learned in the handwritten family history of French Huguenot ancestors, who migrated to London and worked as watchmakers.

“You can inherit a talent for the tiny. It seems there’s a gene for working on a small scale. Phiz inherited from his ancestors this talent for detail. His grandfather taught calligraphy and could draw tiny insects,” says Lester, who rues missing out on this trait. “I like doing little stuff,” she says, “but I’m not careful enough.”

Phiz’s daily work was etching in miniature. For each illustration, he used a stylus to scratch into a wax compound on a steel plate. Then he dunked the image into an acid bath to eat away at the newly exposed steel lines.

“He was incredibly good at it,” Lester said, judging from both the demanding complexity of the work and the amount and speed with which he worked.

In etchings, Lester read Phiz’s story. In place of handwritten letters — most were burned after they were received — drawings filled in the character of the man.

“I read his images, followed his progress,” she said. As she examined Phiz’s drawings alongside the history she researched, she could see ups and downs in Phiz’s work.

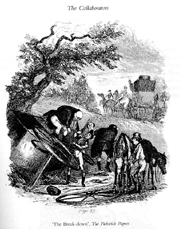

“His work is uneven, but absolutely brilliant when it’s good. When he and Dickens are on a roll together, it’s symbiotic. They complement each other so deeply. In the later books, you can almost see them pulling apart,” she said.

When the style evolved to favor drawings bigger and grander, Phiz fell out of fashion. “He looked dated by the 1860s,” she said. “He was beginning to get left behind.”

It was a lifetime of drawings, though, that helped Lester understand Phiz in a way that musty books couldn’t.

“I knew if he was having an off day. I could tell,” Lester said. Such illustrations would have much less detail and fewer background sketches than when he was really engaged and interested, she says, When Phiz rushed, it showed in a simpler, thinner design.

Another characteristic Lester found in Phiz’s art was his sense of humor.

“There are little jokes everywhere. He would put expressions of surprise or amusement in the eyes of horses for instance,” she says, recounting other works with faces on furniture and tree trunks. “He anthropomorphized a lot.”

Humor is yet another trait Lester traces to Phiz, a characteristic passed on through her father, to her and her daughter. Her daughter is now a stand-up comedian in Tokyo, and works with an improv theater group. Lester says simply: “She’s hilarious.”

Drawing Dickens

To uncover Phiz’s relationship with his most famous associate, Lester followed Charles Dickens’ works. Sifting through Victorian literature wasn’t half bad.

“Dickens writes like an angel. He can have you roaring with laughter. But there’s also a certain sentimentality that can be nauseating,” said Lester, who maintains that it’s Dickens’ comic characters — his rascals, she says — that make him great. “No one can touch him.”

Dickens’ temperament, says Lester, was another story. “He didn’t treat people very well,” she says. Phiz was the Victorian author’s third illustrator. The first killed himself, and the second Dickens fired.

Phiz was just shy of 21 when he began a 23-year illustrating partnership with Dickens.

Though Dickens’ name was what pulled Phiz’s works to present-day recognition — in works like Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, Tale of Two Cities, Nicholas Nickleby and David Copperfield, all published independently with Phiz’s drawings in monthly installments — The central subject always came from Dickens, but Phiz would often add to it with details of his own, Lester says.

“What I wanted to do was show the world that there was much more to Phiz than Dickens. I worked very hard on the list of books that he illustrated,” she said. That’s a list that includes eight works by W.H. Ainsworth, poet Lord Byron’s The Poetical Works by Lord Byron (1850) and Poetical Works (1854) and 17 works by Victorian author Charles Lever.

So Lester unearthed more than she promised in titling her book The Man Who Drew Dickens.

“My effort really was to take him out from under the umbrella of Dickens. He was a man and not an etching needle,” she said. “He was someone you’d like to get to know.”

Scratching More than the Surface

The longer Lester searched, the farther she traveled, and the more she found there was to find.

The quest that sent her overseas to scour the British museum and find long-lost cousins also pulled her back to American soil. With two fellowships, she studied at the Huntington Library in southern California and Harvard’s Houghton Library, a rare book library where she spent a month.

“I had the gift of time, stretches of time when that was all there was to do, to wallow in Phiz,” Lester recalled.

Further travels led her to Australia and New Zealand.

“Writing a book like this is a huge adventure,” she says, particularly if your character has family in fascinating places like Australia.

Besides a collection of worldwide travels, unearthing Phiz gave Lester dogged determination as a “really relentless researcher,” she says. She learned to turn over every stone. She learned to pay attention. And she learned to not give up.

One such puzzle piece came with the mysteriousness of his birth.

“I smelt a rat, and the more I dug the more the rat stank,” she said. “It turns out that his actual parents are adoptive because he was the son of their eldest daughter.”

Life with Phiz

During her years of research, Lester constantly thought of Phiz and craved more history about him.

“I was a crashing bore. I turned every conversation back to Phiz. I didn’t think of much else,” she said. But now, says Lester, “It’s nice to be out of the 19th century. But I do miss Phiz. He was terrific company.”

As Lester talks about Phiz, she sits up with passionate energy, like reminiscing about an old friend. She knows Phiz’s works inside and out.

“I came to the point — a staggering moment — when I knew more about Phiz than anyone else in the world,” she said. That moment of truth came, she says, when she asked her mentor a question, and he turned to her and said, “you’re the expert, you know more about this than anyone.”

“That’s a very strange feeling,” Lester said. “If I’m it [the world’s expert on Phiz], there’s no one else I can ask.”

Being the expert has taken Lester around the world again, this time not digging for clues but divulging her expertise in lectures from Pittsburgh to London to Pisa, Italy.

She’s also back to writing, and this time she’ll turn to fiction.

“I don’t think I’ll ever write another biography. It’s a straightjacket, you have to be very careful all the time,” she says, recounting Dickens’ scholars who eyed her work like hungry wolves, waiting for her to make any kind of mis-step.

“That kind of thing keeps you honest,” she said. “You start asking yourself questions about truth.”

Having found the truth about Phiz, Lester longed to shine his light brightly.

“I wanted him to get a wider audience,” she said. With her book now available in the U.S., she’s hoping you’ll get to know Phiz, too.

Get Phiz-savvy. Order Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens online at www.amazon.com or from www.barnesandnoble.com. Or look for it at local bookstores this summer.