|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

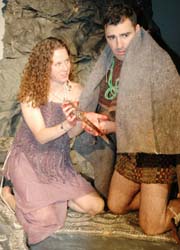

The Stuff that Mids Are Made OfOne in 1,000, Lady Macbeth Flies off into her Futureby Valerie Lester“I’ll be on a destroyer if I fly a small helicopter. Or I could be on a carrier flying a jet. Who knows?” says Stephanie Hoffman as she contemplates her future. Hoffman graduated from the United States Naval Academy as one of 148 women in her class of 976 midshipmen in May of 2005, at the end of a year in which, among other achievements, she was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree, played Lady Macbeth to sell-out crowds and ran her personal best in the Boston marathon. Then she hooked a loaded U-Haul trailer to her car, waved goodbye to her boyfriend and drove from Annapolis to Pensacola, Florida, in the company of her golden retriever. She is now weeks into training as a Navy flyer, her first career choice. Graduating from the Naval Academy gives young people a passport into a world of highly specialized — and often adventurous and exciting — careers that take them flying, submarining and traveling to foreign lands as military leaders. But to open the doors to such a future, you’ve got to have the right stuff. Here’s how one woman packaged those elusive ingredients into a future full of possibility. Nature, Nurture and Opportunity “I’m the baby. I’m one of three girls. Irish Catholic, from Easton, Massachusetts,” said the neatly packaged Hoffman, she of the copper-red hair, hazel eyes and great smile. “My parents were in the Navy before they had kids. My mom wanted to be a cop, but she’s four-foot-11-inches tall. The Navy took her and she became a WAVE.” Hoffman’s father was a Navy medic deployed with the Marines; both parents left the Navy when they started their family. “I had a lot of self-discipline coming in to the Naval Academy,” Hoffman says. “My two older sisters are close in age, and they fight. I didn’t want to do that. I liked to solve problems. Even when I was little, I was making macaroni necklaces in a disciplined way.” When her middle sister brought home an ROTC brochure, Hoffman studied it with fascination. “You get to jump out of a helicopter! I want to do that,” she squealed. She marched into her school counsellor’s office and announced her intention. “How about West Point?” her teacher inquired. “How about the Naval Academy?” asked her father. “Okay, whatever, sure,” said Hoffman. Even as an eighth-grader, she was already displaying characteristics that would sustain her at the Naval Academy: courage, determination and, above all, flexibility. On a family vacation to Florida, the Hoffmans stopped in Annapolis. “Whoa! This is real pretty,” Hoffman said. “Guys in uniform! Yay!” She didn’t bother to look at West Point and was admitted early to the Academy. Woman to Midshipman The first year was a shock. Time management, heavy-duty academics, navy regulations and traditions, shouts and reprimands, sexism, co-ed dorms and sleep-deprivation were all obstacles to surmount. “Mom and Dad weren’t like a military family,” Hoffman recalls. “If I got yelled at, it was because I deserved it, not because someone needed to yell at me. I also had my first experience of someone saying You can’t do that because you’re a girl. Coming from the Northeast, I had never heard that before.” As Hoffman met people from all over the country, she butted into strange new opinions. At first she argued until she was blue in the face; then she learned to keep her mouth shut, realizing that effective actions speak louder than words. Change, she believes, is possible by example. “Being a woman at the Naval Academy is usually great, but I was stunned at first, not having grown up with brothers. Your next-door neighbors are guys; but living co-ed is definitely the way to do it,” she says. “Now I know how my dad feels with all his women.” The Academy is approximately 18 percent women. Struggling to balance the demands of her plebe year, Hoffman found sleep deprivation was her greatest enemy. She quickly learned the importance of time management. “I was always trying to get my stuff done so I could get to bed. I had my little checklist, do this, do this, do this. You’re so exhausted when 11pm comes around. But it forces you to say Suck it up and do it.” And indeed she did. She tied her wild red hair back into the regulation knot and set to work. Hoffman did not find the Academy’s academics particularly difficult. “On average, I had five to six hours of homework a night,” she says. Humanities came more easily to her than science, but even in English she admits she never had an easy course. If she had time off, she would work on the simpler homework first, saving more difficult material for group study. “The sciences were harder,” she says. “I don’t enjoy doing mathematical equations. I’m an English major, but my degree is a bachelor of science because you have to take so many core science courses.” Becoming Lady Macbeth In the Masqueraders — the midshipmen’s drama group, begun in 1845, is the oldest extracurricular activity at the Academy — Hoffman found not only creative refuge in a sea of rules but also new passion. “The way I got into acting,” she says, “was at the end of my youngster year [sophomore year, in civilian terms] when I auditioned for a collaborative play about the trial of St Joan. It was snippets from different works about her life.” The cast of five women each played Joan or people who were trying or supporting her. “It was minimal,” she says. “No costume changes, no set. All body movement.” Next came Chaucer in Rome and The Pajama Game. Then in her final year at the Academy, Hoffman stepped onto the stage as Lady Macbeth. “It’s a huge burden for an actress,” she says. “It’s like Hamlet for a man. Everyone has a different portrayal of her: seductress, murderer, involved, less involved.” The play was directed by Professor Christy Stanlake, who worked with Hoffman and Jack Treptow (Macbeth) to produce a sexually charged relationship, with Lady Macbeth subtly controlling her husband. “I knew Jack before Macbeth,” Hoffman recounts. “We both sang in glee clubs, but we had never acted together. We had great chemistry, and Jack was easy to work with. We had three kissing scenes, and he would say, ‘Are you comfortable with this?’ We’d kick everyone out of the theatre and say, ‘Let’s now be vulnerable.’ We’d get into huge arguments and translate that into the play. Back stage, I’d say, ‘Shut up, Jack,’ And he’d say, ‘You are controlling me.’ And we’d say things like, ‘You suck!’ ‘No. You suck!’ And Dr. Stanlake would say, ‘Get bigger. Get down and nasty.’ That helped us immensely.” Hoffman worked particularly hard on her suicide scene, visualizing each segment of the soliloquy as she reacted to events that had already happened, like Duncan’s blood on her hands and the bell ringing. “I pictured a dead guy in front of me,” she says. “Once you get that realization, it’s scary seeing a dead person in front of you that’s not there. That unnerved me and made me more vulnerable.” Richard Montgomery’s set also helped Hoffman with her character. The actors assisted the technical crew in building the bleak, earthy environment, dominated by a huge Celtic cross. Once it was all assembled, Hoffman felt empowered by her surroundings. Montgomery also designed the costumes, but the cast had to make them. “Richard came in with all these random rugs and sheets and tattered things, and we all said, ‘You’ve gotta be kidding,’” she recalls. “The bodice I wore for most of the play was actually a bathroom throw rug. When I first put it on, I looked 50 pounds heavier, so I took shears and trimmed it down. We laced it up the back like a corset.” With the darkly glowering set offsetting her pale skin and unruly hair, her skimpy costume enhancing her sexuality, secure in her lines and thoroughly rehearsed, Hoffman became Lady Macbeth on the stage of Mahan Hall. The audience was stunned by the erotic frankness of her performance. Among those present were her parents, who flew down from Massachusetts. “It was hard doing kiss scenes in front of my father, but I think they were really happy with how everything came together, the set, the characters, the ensemble,” she says. Macbeth was Hoffman’s last production at the Naval Academy, and she says that she will have little time for theatre at Pensacola. But she doesn’t plan to give it up forever. “Now I know I have a passion for it, I can put it on the back burner,” she says. “Theatre is more about raw talent than movies, and you don’t have to be 20 and blonde to get into it. It’ll keep.” Branching Out Hoffman balanced becoming Lady Macbeth with the Academy’s demands. She managed to keep up with her classes: English, Spanish IV, naval law, thermodynamics and creative writing. She maintained her brigade staff position as the alcohol and drug education officer, working with the administration on abuse prevention. Hoffman was also in charge of seating dignitaries at Naval Academy parades as a member of the Protocol Staff. And she was president of the Women’s Glee Club, which meant attending choir rehearsals as well as play rehearsals. “I was constantly running around like a chicken with my head cut off,” Hoffman says, laughing at the memory. “Just thinking about it makes me feel tired.” She found relief from the stress in running, running as hard as she could. “You have a pair of shoes, some shorts, and you can do it anywhere,” she says. “It’s part of the way I define myself. When you meet someone and say you’re a runner, there’s an understanding. Oh, you like pain, too!” She has run three marathons and one ultra marathon of 50 miles. Guess which she did first? Yes, the ultra. A friend asked if she wanted to give it a try, and she said sure. She watched to see how others handled the challenge, paying particular attention to those who had run the same marathon the previous year. “I noticed they walked most of the uphills; they picked up M&Ms, pretzels and Gatorade at every rest stop. I did the same.” She completed all 50 miles. Since then, Hoffman has run the Marine Corps Marathon and two Boston Marathons. “The actual running is easier in the ultra,” she says. “I can run an 11-minute mile for ever. But I was more sore afterward.” Because the run fell during a Thanksgiving recess, Hoffman went home afterward, where her mother, now a certified massage therapist, went to work on her tired muscles. Toward the end of her time at the Naval Academy, Hoffman had to decide which direction she wanted to follow. Being a naval aviator sounded glamorous and is the choice of about one-third of every class. Other paths include surface warfare, Marine Corps, and submarines. Graduates, who do not necessarily get their first choice, can also select among fields as various as special warfare, special operations, medical corps, supply corps, intelligence, civil engineer corps and even cryptology. But Hoffman initially balked at flight. “First, I wanted to be a JAG, that’s a Navy lawyer, but you can’t do that straight out of the Academy. Scratched that off the list. Flying? Nah. Marine? Nah. Wanna go on a boat? Nah. So I went back to flying, even though I had a fear of crashing. But once I realized that I’d be the one flying and certainly wouldn’t want to kill myself, I thought I’d be okay.” The Naval Academy requires all potential pilot and flight officers to go through an initial flight-screening program. Each one flies 25 hours in a small plane like a Piper Cherokee Warrior out of a local airport. Hoffman flew her hours out of Lee Airport in Edgewater. “It was a liberating feeling, at times a bit scary, being up in a tiny Piper Cherokee Warrior flying over Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey. However, after I was about 20 minutes into the flight, I said to myself, ‘Relax, you can fly this. Look how gorgeous it is down there.’” Earning Her Wings Hoffman has now stepped onto the next stage of her career. At Pensacola, she attends classes taught in weekly segments with a test at the end of each week. One by one, she knocks off aerodynamics I and II, engines, FAA regulations, aviation weather and navigation. Swimming has eclipsed marathon running for the time being, since each student must become proficient at survival swimming. She’ll jump from a five-meter board, tread water and swim a mile in full flight gear. If Hoffman passes all her tests, she will graduate from Aviation Pre-Flight Indoctrination at Pensacola and will move to Vance Air Force Base in Enid, Oklahoma, to begin Primary Flight Training. “So far, it has been a lot of work, but I am enjoying working toward my gold wings,” she said. Fueling Her Fire From transforming herself into a temptuous murdereress on stage to running ultra marathons to using discipline learned at the Academy in flight school, Hoffman calls on lessons learned at home. She credits her supportive parents plus her fractious sisters, from whom she learned that confrontation is not necessarily the best way to handle opposing views. Hoffman has inherited intelligence and physical competence; she sees setbacks as opportunities and has learned to keep her passionate Irish temperament — the side that served her so well as Lady Macbeth — in check when necessary. Rigorous demands on an already driven young woman have produced an outstanding performer. Now, not even the sky’s the limit. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

|