17 Years of Living Green with Bay Weekly

On Earth Day 1993, New Bay Times was born — and born green.

A lot has changed since then. One big change: We’ve learned that good intentions are a lot harder to realize than conceive. Who’d have thought back then that newspapers would be caught in the jaws of evolution? That the Bay would be so hard to save? That climate change would be running toward us with such speed? That all the strides we’ve made have been like walking into an ocean, where you step forward only to get pulled backwards.

Our name is another of the many changes. In our second year, we ambitiously added Weekly to our name — and to our production schedule. We could make New Bay Times – Weekly, but people wouldn’t say it. So on our millennial birthday, we shortened four words to two, becoming Bay Weekly.

A lot has changed, but a lot has stayed the same.

Seventeen years ago, we promised to green your life with smart, stories that made reading a pleasure and brought sustainable living closer to your home, your neighborhood and the Eden where we live, Chesapeake Country, about which Captain John Smith, wrote: “heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation.”

On this Earth Day, our 17th birthday, we looked back to see how well we kept that promise. From all those years, all those volumes, all those pages, all those stories, I’ve compiled Bay Weekly’s first annual Green Guide.

As you read, remember that you’re reading history. You can’t join Pat Bramhall’s CSA (Pat died in 2003), and Bill Matuszeski retired many years ago as head of the Chesapeake Bay Program — though he still has plenty to say on how far restoration has come, or hasn’t.

But you will see how the innovations of the past 17 years — and Bay Weekly’s reporting of them — have shaped an ethos. So that in 2010, we’ve all made strides toward living greener.

– Sandra Olivetti Martin, Bay Weekly Editor and Publisher

How Does Your Garden Grow?

Organic gardening ensures that you’re getting the best produce with the least impact on Mother Earth

Organic farmers like to say that rather than fighting off disease and pests, they spend their time building up the health of the soil — with crop rotation, earth-conserving tillage, mulch and compost and testing their soil to learn what other additives might be needed.

“Organic farming is taking 1,000 pounds of anything you can find and turning it into a teaspoon of soil,” Pat Bramhall quotes, loosely and laughingly. If the source has flown her mind, the substance has not. Leaves, mushroom compost, cover crops ploughed into the fields that grew them, wood shavings saved by an Annapolis cabinetmaker: New earth ingredients are on organic farmers’ minds night and day

At Pat and Bob Bramhall’s organic farm in Lothian, Pat is expecting a bumper crop of asparagus now that she’s fed her beds with mushroom compost, a rich, light mixture of horse manure, chicken droppings and gypsum. She bought a 100-cubic-yard trailer-load from an organic mushroomer in Pennsylvania.

Pat’s back is still sore from planting 200 pounds of seed potatoes. Only the stooping was work; she bedded her potatoes in a thick cover of shredded leaves, where they’ll sprout effortlessly.

The Bramhalls have owned their farm for 20 years. For two, they’ve devoted their land and labor to Community Supported Agriculture. So for 16 weeks beginning May 24, their shareholders carry home vegetables, berries and herbs and help, when they choose, in the growing. Shareholders with the Bramhalls enjoy the bounty and diversity of a locally grown, strictly fresh, toxic-free harvest at an amazingly low cost: $240.

1993: Vol. I, No. 2 • Sandra Olivetti Martin

Pass the Salt, Skip the Poison

Modern-day farming returns to nature

“We didn’t give a second thought to the worm in the core when I as a boy. It was considered part of the apple,” says Dr. Donald Bills, who coordinates sustainable agriculture research at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Research Center at Beltsville.

That’s where the standards for American farming — the ones that eventually run off to the fields through the cooperative extension network — are set.

“We’re trying to find ways to decrease our reliance on petroleum and chemical resources, all of which are exhaustible,” explains Bills. In sustainable farming, an unbroken chain of renewable resources replaces the circle of poison that began in America in the 19930s, when farmers turned to chemical fertilizers to energize worn-out soil.

The chemicals took the worm out of the apple. We didn’t notice the snake in its place until Rachel Carson brought it to national attention in Silent Spring. In the years since Silent Spring, we’ve learned that chemicals solve some problems, but they create more, for birds, humans and Chesapeake Bay. That’s why sustainable researchers like Bills are looking for ways to grow perfect apples without chemicals or worms.

They’ve found, for example, that we don’t need chemical fertilizer. Nature makes a better fertilizer at a fraction of the cost. Nature’s secret is the legume. Plant a fall field full of hairy vetch, which sustainable agriculture researcher Dr. Aref Abdul-Baki has proved the most efficient of all the legumes. Let it grow all winter. Mow it in June, and drill your plants right into the blanket of green mulch made by your mowed vetch.

What about the worm?

Worms of many sorts plus whiteflies, aphids, spider mites, borers, wilts and fungi of all sorts are under assault at Abdul-Baki’s Beltsville facility. Instead of bombing them with broadly toxic chemicals, scientists are tinkering with their genes and sex drives.

“We feel we are developing farming for the next century by returning to nature,” Abdul-Baki says.

1994: Vol. II, No. 22 • Sandra Olivetti Martin

King of the Crab Experts, Scientist Eugene Cronin

Treat crabs as a single stock and quit managing them piecemeal

Gene Cronin was one of the first scientists to sound alarms about problems in the Chesapeake. Here he tells how that came to be:

When I was doing my early work in the 1940s at the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, we didn’t see many problems. You could go out any time and catch fish and buy crabs. You could always find oysters. The water quality was generally good.

We saw some problems with pollution and overfishing, but not much. We knew sediment was running off land at every storm and going into the Bay. We knew that we kept dredging channels and we didn’t know what to do with the stuff. We piled it up all over the place and hurt the Bay. Even then the Bay seemed to be able to take much of the pollution we were putting in it. It seemed resilient.

Around 1970, the Bay became less productive. Water quality went down. We were putting in too much fertilizer. We had overfished some species. That’s the period when I and many others began to say, Hey, we’re getting in serious trouble.

I think the research and studies I did on the crabs were worthy and constructive and helped us understand what we must do, which is mostly treat them as a single stock and quit trying to manage them piecemeal.

On other life’s achievements:

One separate item that was unexpectedly important was when I served on a panel to review the use of DDT and whether we should discontinue it. We went through a series of hearings and reviewed the literature and came to the conclusion that DDT was threatening wildlife, fish and mammals and, to a tremendous extent, birds. There were irreversible losses.

It takes a long time to get DDT out of the environment. But that’s probably the basis for the recovery of the eagle, the osprey, a lot of our carnivorous birds and perhaps some of our fish.

1995: Vol. III, No. 36 • Stephanie Barrett

Pulitzer Prize-winning Author William Warner

In the next decade, we’ll have a better idea of whether we started soon enough to protect things

In 1975, William Warner had done almost no serious writing. He’d spent most of his career as a Foreign Service officer. But his love for the Chesapeake and an idea for a magazine article turned into the best-selling Beautiful Swimmers.

Warner on his Beautiful Swimmers:

I just took this year off with this ill-formed idea that I wanted to write. By that time, I had just sort of informally had an agent — Marie Rodell who was literary mentor and encourager to Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring.

I gave Marie what I thought would be a magazine piece, a long day with a crab potter. They started sending me these little zingers: We like the hors’ d’oeuvres. Are you thinking about going the full course?

After a while I said, Well I know the Bay pretty well …

The field research was fun. You must listen to speech and the vocabulary to really learn. Like Doublers are out there, but they ain’t for everybody to catch. I was absorbing all of that.

The Bay has so deteriorated that I thought I couldn’t leave it forever the way it was in the book. So with the new edition (1994), I wrote an afterward. I started out with the Tom Horton theorem: that when books come out about fishing communities and marine resources, it’s about the degree that those resources and that way of life are being depleted.

I have a feeling that in the next decade, we’ll have a better idea of whether we started soon enough to protect things. It does seem to be at a critical juncture.

1995: Vol. III, No. 33 • Bill Lambrecht

Happy Trails to You

Greenways connect us to the natural world

Skunk cabbage, Jack-in-the-pulpit and mountain laurel flourish in the undisturbed richness of the wild forest, while blue bonnets and Baltimore orioles favor the open fields of backcountry Maryland.

From footpaths following deer trails to eight-foot-wide macadam roadways, there are as many kinds of trails as desires to use them.

Whatever trail you follow, by whatever means, you’ll find a buffer from mass-processed modern life plus — in varying degrees — an experience of lushness on your own terms and speed. A family outing on the unpaved trails along the Patuxent Regional Greenway through the Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary or the hiking paths through Quiet Waters Park on the edge of Annapolis: Both are good for what ails you, and the price is right — free!

Trails are, after all, “the only recreation you can use in all seasons, without special equipment or skills and by all ages,” says Ann Ridgely, executive director of American Trails.

Trails are, naturally, connectors from one place to another. They are also the conduits for biking, hiking, horseback riding and skating. Unlike rugged trails, trails used by more people are mapped and maintained. The Maryland Greenways Commission establishes trails and proposes new ones. These trails, or Greenways, may stretch across federal, state and private lands.

Marylanders enjoy “300 to 400 miles of existing trails serving a system of hubs and corridors,” according to Teresa Moore, director of the commission. “The hubs are forests, parks and wildlife management areas, and the trails provide access from one place to another. Proposed Greenways to link places still inaccessible by trail will add another 500 miles to the system.”

1996: Vol. IV, No 17 • Aloysia Hamalainen

Bill Matuszeski: EPA’s Man on the Bay

The good news is that the Bay is a pretty resilient body of water

Editor’s note: In 2010, it’s déjà vu all over again, with the 2000 goal still unmet and the same words coming from different mouths.

This is an important year because we are supposed to be figuring out whether or not we are going to meet our most important goal, which is to reduce nutrients coming into the Bay by 40 percent by the year 2000.

There are two problems with meeting that goal. One is that we’ve been very slow to gear up to the level of effort we need to achieve it — that is, to clean up the sewage treatment plants, to work with farmers on reducing fertilizer from manure and trying to deal with runoff from urban areas.

We’re behind in gearing up, on the one hand. And on the other hand, it’s going to be difficult to do a lot more between now and the year 2000 than we already do.

Are you saying that people need to be prepared for delays?

No. I think that people need to be prepared for the fact that it’s going to be a very difficult job to get our numbers up to 40 percent. That’s the bad news side of it.

The good news is that this Bay is turning out to be a pretty resilient body of water.

1997: Vol. V, No. 4 • Bill Lambrecht

Feeding the Earth: A Compost Convert’s Testimony

From garbage to garden

I remember composting from a long time ago, though I don’t remember calling it that. Back then it was the leaf pile.

Somehow, the pile never grew beyond the former year’s boundaries, and renegade pumpkin seeds took root and prospered. Eventually the crumbly black soil in the center was returned to the garden, where it grew a new generation of vegetables and flowers. But a kid doesn’t care about making good dirt, just playing in it.

I forgot all that until — 20-some years later — I bought my own house. My house was fine, but my dirt was, well, mediocre.

Dig a hole and put kitchen scraps in it, a friend said. I wondered at her wisdom. Her yard was table-scrap heaven, a chuck wagon raided by misbehaved dogs. Still, her soil grew darker, her plants grew bushier and her flowers brighter.

So I dug a hole and filled it from my kitchen. Besides, I thought, who’s going to know what I put in my compost? Soon I found out.

I watched as my new neighbor retrieved her over-plump beagle from my backyard. The dog had discovered my compost hole, and he was particularly fond of bagels.

A class, I decided, would help my quest. So I showed up at 9:30 one morning for Anne Arundel County Recycling Division’s Backyard Composting Workshop. I and 60 other people, plus the 80 or so who couldn’t get in, had the same idea.

No meat, said Master Composter Lewis Shell, no varmints. (Except for bagel-eating beagles.) Mix your browns and your greens equally. Turn it once a week. Keep it as damp as a squeezed-out sponge. As well as advice, I got a free composting bin to get started.

My neighbor and I share a compost bin now, because neither of us can fill it up alone. Between us, we’re making some good dirt.

The only thing I needed to buy was a five-tined pitchfork (smooth-pointed tips allow leaves and chunky stuff to slide off easily). We set up the bin and lined the bottom with sticks to allow air to circulate underneath. Then, with a little bit of compost from an earlier attempt, we added grass clippings and leaves.

Now when I trim my houseplants or peel a banana, I save them in a basket by my front door. Even at work, I gather scraps from co-workers’ lunches. At the end of the day, or whenever I happen to walk by the bin, I empty a whole quart of garbage to return to the earth. Never a bad odor greets me, just an earthy smell that doesn’t a nose crinkle.

But if your dog is missing, you may find him munching on a bagel in my backyard.

1998: Vol. VI, No. 16 • Betsy Kehne

First Person: My Year with the Oysters

Despite warnings, we took losses personally

Editor’s note: Glover, an early oyster gardener, volunteered as a citizen scientist in Academy of Natural Sciences’ year-long study of the fate of oysters on the Patuxent River.

Standing on our pier on a bitter cold afternoon early in 1999, we can imagine the Patuxent River of a century ago when oyster bars covered the bottom of the river and skipjacks harvested 15 million bushels a year.

My husband Ray and I have added a bit of hope over the last year.

We’ve helped George Abbe and Brian Albright, Academy of Natural Sciences’ oyster researchers, learn how a devastating disease strikes along the river. As we haul our oyster tray onto the dock for the last time, we’re sorry our part is ending.

Last January a metal tray holding 100 live Broomes Island oysters was anchored to the side of our pier. Through the rainy months of spring, the heat of summer, the cool of fall and the harshness of December, we faithfully pulled up our oysters to measure their growth, count the survivors and discard the dead.

This scene was repeated on 21 sites on both sides of the river, from the mouth of the Patuxent in Solomons to the Benedict Bridge. All 60 volunteers, the citizen scientists in this oyster research project, have seen it through, although two oyster trays disappeared.

You know people are involved when a neighbor in the local grocery store leans over the produce section and whispers, “Our oysters grew faster than yours.”

Through the winter and spring of 1998, all was well. But as summer moved in and water temperature rose, our oysters began to die.

As the oysters fed on bacteria, they swallowed the dermo cells. Abbe compares dermo with the flu: “Oysters can be infected from a light dose, like a person’s having a fever, to a deadly dose, like a person getting pneumonia.”

Despite the warnings, we took it personally. First it was just a few. Then, in August, we lost five. At the end of the year, our hundred oysters had dwindled to 83.

In salty water near the river’s mouth, half of our oysters died. In fresher water mid-river to Benedict, about 10 percent died.

1999: Vol. VII, No. 11 • Carol Glover

Trash in Afterlife

The stuff you throw out never really goes away

It’s only natural that America has the world’s mightiest and most agile trash collectors — plus the world’s most impressive garbage trucks. We have the most trash. That said, let it also be said we have found amazing ways to deal with it all, be it our Big Wheels, dirty socks, beer cans, newspapers, tires or burned-out frying pans.

The way we bury trash is impressive. Landfills have come a long way from a simple hole in the hinterlands.

“Think of a landfill cell as a trash pie,” says Beryl Eismeier, Anne Arundel County’s recycling manager. “A crust, or liners, on the top and bottom, and trash in the middle.”

Over the bottom liner, installed to prevent seepage, workers drop a layer of trash, tamp it down flat for space, stabilize it with a layer of mulch, then add more trash until finally a landfill pastry is created. A cell may be dug as deep as a 20-level underground parking garage. It may be stacked as high as a 30-story building. When this pie is filled, it makes a nice mound that is capped, covered with two feet of soil and sodded over.

But as with Edgar Allen Poe’s telltale heart beating beneath the floorboards, entombment is not the end of the story. The trash within is always stirring, shifting and festering. “We’ll be worrying about that garbage a long time,” Eismeier says.

Even more impressive is the way we resurrect our trash.

If you’re a typical Anne Arundel County resident, you cast off about three pounds of trash a day, two of which are probably recyclable.

When you consign that old T-shirt or broken bottle to your trash, you doom it to an eternal, though restless sleep. But when you put it in your recycling bin, you grant it a possible future. Once the recycling truck finishes its route, with a trail of emptied and overturned bins in its wake, it heads for the pearly gates: a recycling center.

2000: Vol. VIII, No. 41 • Christy Grimes

Hybrids Hit the Road

A new generation of environmentally friendly autos is arriving in Chesapeake Country. We took a trip to find out what they’re all about

What the heck’s that thing you’re driving?

If Jerry Karsh had a nickel for every time he’s heard it, he’d be filling up his tank for free. Of course, he doesn’t need many nickels considering that he’s getting 46.5 miles per gallon driving his new gas-electric Toyota Prius hybrid.

Crammed under the foreshortened hood of the Prius is your typical 1.5 litre, 70-horsepower gasoline engine — plus a 44-horsepower electric motor. Between the rear wheels, dividing the passenger compartment from the trunk, is a battery, about the size of a very big suitcase, putting out 273.6 volts.

As a gas-electric hybrid, the Prius uses both modes of power and innovations that shut off the gasoline motor when the car is idling at an intersection or in traffic. The crossbreeding inside this shiny little package makes it the long-awaited answer to the environmentally urgent question of how we’re going to start driving cleaner.

A century ago, when automobiles were a bright new idea, electric cars stood on equal footing with gas. Thomas Edison invested heavily in electric cars, envisioning then as the eventual winner against gasoline. But gas won out, and that has made all the difference.

Electric cars run cleaner than gas cars, and, of course, they use less fuel, something to think about in these days of buck-50 gasoline. The problem — which some say we’ve been slow to solve because of the profit motives of interlocking petroleum and automotive industries — has been how to get an electric power plant to fit under the hood of a car.

At Bay Weekly, we’ve avidly watched an array of experiments to solve that problem. In our first summer, 1993, writer Bob Weckback drove an experimental electric car. “You were going fast at 35 miles per hour,” he recalled. “And you knew you weren’t going far before you had to plug in.”

We’ve seen wonders at the annual Tour de Sol rally pitting the country’s cleanest-running, most fuel-efficient cars, trucks and buses in a 250-mile event from New York City to Washington, D.C., during Clean Air Week in May. Pretty much, they’ve been science lab experiments on wheels that have yet to make it to mass production.

At the millennium, the divergent paths met again. The big surprise is that the technology is nothing new. Hybrid technology has been in use in diesel locomotives for decades. The diesel drives a generator, which supplies electrical energy to the motor, which runs the train.

We tested a hybrid over the holidays in San Francisco, one of the nine American cities where you can rent them. Instead of a Toyota Prius, our car was a Honda Insight. We had rented one of 4,000 Insights imported in the hybrid’s first year in America.

2001: Vol. IX, No. 3 • Sandra Olivetti Martin

Rain Gardens in Dry Times

Every drop counts

It’s sweating hot. Tan-brown snails have chewed the stems out of the green pattypan squashes. Day lilies have thrown off their dry orange heads. The magenta of coneflowers has faded to the anemic pink of a lipstick not popular since the 1960s. Clouds hold themselves intact, allowing the merest dribs and drabs to fall on the parched young hydrangea.

It will rain again. It must rain again. When it does, I intend to put every precious drop to good use.

Earlier this summer [www.bayweekly.com/year02/issueX25/dockX25.html] Juanita Foust taught us how to catch water in a rain barrel and put it to garden’s purpose. I meant to buy a rain barrel, but I haven’t done it yet. Now Corinne Reed-Miller shows us how to take one step out of the watering process.

Reed-Miller put a rain garden in her Admiral Heights yard this spring. It looks a lot like a regular garden, but it’s set down into the lawn rather than raised up.

“It’s easier than you can imagine,” she says. “I fretted for a month before I did it, but it’s not that different from a regular garden.”

The beauty of a rain garden — this one is alive with black-eyed Susan, coreopsis, bee balm, swamp milkweed and a naturalized Lord Baltimore hibiscus, with room still for blueberry bushes — is not just the view but also the clever use of water. A rain garden grows with rainwater directed to it from the house downspout.

The hardest part of making a rain garden is that you have to start with math. Fifth grade math. Measurements. Multiplication and division.

2002: Vol. X, No. 32 • Sonia Linebaugh

Wrangling Oysters Out of Trouble

A pearl of an idea for bringing back the Bay and its delicious oysters

Time was when crushed oyster-shell roads sparkled in the sunlight leading to packinghouses along both shores and many tributaries of Chesapeake Bay. Now, wild oysters are nearly gone from river bottoms and Bay reefs, and with them much of the Bay’s oyster industry.

At the end of December, 2002, Maryland’s harvest was a record low 28,000 bushels, putting us in line for the worst harvest in history when the total is figured in March.

It’s so bad out there that some — scientists and watermen — have given up on our Bay’s poor old Eastern oyster.

There’s even a substitute waiting in the wings. Carassostrea ariakensis, a non-native Asian oyster species that’s won hearts in Virginia, seems to have all the good of its native American cousin with none of the bad [www.bayweekly.com/year02/issue10_03/lead10_03.html].

But not everybody’s ready to throw in the towel on Carassostrea virginica.

Down on Circle C Ranch in St. Mary’s County, Richard Pelz thinks he’s got a pearl of an idea for bringing back both the Bay and oysters you can eat.

The secret, he says, is his floating reef, under patent as the Biological Nutrient Control System.

To understand how salvation might work, you have to imagine how bivalves and Bay work together. When the Bay was healthy, so were oysters, for each satisfied the other’s needs. The Bay brought the oysters sunlight and nutrients; the oysters filtered the Bay, keeping it clean. Only when human acts broke that system down did disease run wild.

Put enough oysters back in the Bay, Pelz says, and the balance will be restored. As farmed oysters grow, they’ll filter the water from the top down, stimulating photosynthesis and creating oxygen to restore the symbiosis of bivalve and Bay.

“The native oysters grow fine,” says Pelz. “They just need a chance.”

2003: Vol. XI, No. 2 • M.L. Faunce

To Change the Bay, You Can’t Be Afraid to Get Your Feet Wet

Nothing gets you motivated for action like connecting firsthand to our rivers

In Calvert this weekend, the Patuxent River’s passionate politician, former Maryland Sen. Bernie Fowler, continues the tradition he began 16 years ago, in 1988, with yet another Patuxent River wade-in. This June 13, Bernie plans to shift the emphasis: from simple community education to prodding decisive political action.

He’ll challenge all who speak from the podium this year to make clear commitments: what exactly they will do before the 2005 wade-in to bring this river back to health.

If Bernie Fowler says we must save the Patuxent River, and Walter Boynton, of Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, says that we can do it, surely Maryland politicians will decisively fund sewage treatment, demand better storm water retention and cleaner air.

In real life, predicting political actions is as risky as predicting horse races.

Howard Ernst offered the first analysis of the political situation around the Chesapeake and its rivers in his 2003 book Chesapeake Bay Blues. “Public policy,” he wrote, “tends to follow the course of least resistance. Political actors support economic growth and prosperity.”

But what kind of growth and prosperity? From the moment that English colonists set foot in the land they called Maryland, economic growth and prosperity depended on freely taking the land and waters of this place along with its fish and fowl, birds and mammals. Thanksgiving was expressed to God, and colonists worried about the silting in of the rivers. But the political action to protect the waters never balanced economic growth and prosperity.

How do we change old habits to new, sustainable ones?

Clearly, politicians need support from citizens who grasp the doability of Walter Boynton’s outline of solutions and will join in demanding public policies that protect our rivers — and thus the Bay. Letters and e-mails are a start. But nothing gets you motivated for action like connecting firsthand to our rivers.

A public ritual, like the river wade-ins happening across the region, helps develop that connection and the commitment as a community.

2004: Vol. XII, No. 24 • Sara E. Leeland

Where Have All the Songbirds Gone?

Open spaces are disappearing quickly, and their bird residents with them

It’s survival of the fittest — and the luckiest — as adapters abound and the displaced disappear.

Birds vie for position at the feeders outside my kitchen window.

Puffing up his red breast feathers, a male house finch tries to dominate a feeding perch, patrolling from one end to the other. As the bird chooses to lunge at competitors rather than eat, I smile over my morning coffee.

Then I see it. In flutters a male goldfinch just changing from his drab olive-green winter attire to his brilliant gold mating plumage. I wonder where he has spent his winter. It might have been only a few hundred miles away or as far as southern Mexico. He might even be part of a flock that braved the Maryland winter.

When the long journey of spring migrants is done, birds come home to problems in their summer breeding grounds, too. Humans are the birds’ biggest competitors. Open spaces are disappearing quickly, and their bird residents with them.

Along with open spaces, we’re forever losing forests, with what remains becoming more and more fragmented.

Songbirds in Bay Country face many obstacles. Locally they must contend with loss of habitat and cowbirds invading songbird nests to lay their eggs. Birds that migrate face additional problems, such as loss of stopover and winter habitats, including, for some species, the destruction of the tropical rain forests.

But are songbirds really declining? It is a complex problem with no simple answers. Opinions vary, even among experts.

For one thing, Bay Country hosts many songbirds that we can see, but also many others that we often only hear.

For another, many songbird populations are in decline, but not all. It depends on their habitat and how well they can adapt to humans.

2005: Vol. XIII, No. 17 • Vivian I. Zumstein

Where the Three Little Pigs Went Wrong

With forethought and planning, we can build shelters not only for safety and comfort, but also for our future and that of our environment

The most popular materials for home building, with some variation, remain much the same as those used by the Three Little Pigs in Joseph Jacob’s 1890 classic: straw, sticks or bricks.

The first little pig, who was more fun-loving than serious, chose straw for his house. As a child, I thought this little pig was foolish, which was what Jacob wanted me to think. Why would anyone in her right mind build a house out of straw? As well as being easy to blow down, wouldn’t it also fill with mice and insects? What about heating, cooling and ventilation? Surely one couldn’t put a fireplace in a straw house. And how would you install windows?

But then I was only looking at the negatives, while others have found positives in building with straw. Romey Pittman and Sam Droege constructed some of Anne Arundel County’s first straw bale buildings in Harwood in the late 1990s.

“It is a great building material because it’s cheap, it’s readily available, it’s environmentally sustainable, and it’s great insulation,” says Pittman.

The second little pig chose sticks as his basic building material. The homebuilding industry in America has had a long and profitable love affair with wood-framed houses. Quick, easy and inexpensive, this building material remains popular for the same reasons the second pig chose it.

Lately, however, we’re seeing too many similarities between the fates of our stick-built houses and the second little pig’s.

Jacob’s third little pig comes off as the smartest of the three. His brick house survives the fierce huff-and-puff test of the Big Bad Wolf.

As strong as the little pig’s brick home with fireplace was in the face of danger, this dwelling, too, has drawbacks, for brick is not all that energy efficient, nor are fireplaces.

Alternatives to brick that this little pig might consider are based on cement, an ingredient of concrete. There is true value in building with insulated concrete. Plus, concrete homes have a proven track record of withstanding the ravages of hurricanes, tornadoes and fires when all the stick-built houses around them are in ruins.

2006: Vol. XIV, No. 15 • Maureen Miller

Energy Wise

At these prices, why not switch to clean energy?

My head went spinning faster than my single station watt-hour meter when I opened my last BGE bill of summer 2007. It had jumped from $200 to almost $300, a 50 percent hike.

I’ll admit that my air conditioner units and ceiling fans whirr at top speed around the clock, my computer shuts down only when I sleep, I read my refrigerator like an open book and my sons’ reptile tanks are regulated with heat lamps, fluorescent bulbs, water filters and thermometers.

But I do hang my laundry to dry, run my dishwasher only sporadically and keep the blinds closed and my lights off all summer.

The big jump had nothing to do with my family — or yours — using more electricity. Or even with rising fuel costs. It has everything to do with long-term electricity markets, according to Public Services Commission economist Phil Vanderheyden.

Back in 1993, BGE wanted to raise its rates. As a public utility, the electricity producer needed the permission of Maryland’s Public Services Commission. To get the big benefit — $300 million — the utility had to pay a big price. BGE struck a counter-intuitive deal with the commission: It would cut its rates by six and a half percent and hold the cut until 2006. Then whatever the market bore, it would charge.

“The energy hike is a step toward forcing consumers to re-think their current lifestyles,” says Gary Skulnik, president of Clean Energy Partnership of Silver Spring, a non-profit group founded in 2004 to reduce global warming and air pollution by offering clean energy.

Electric bills are like taxes. You pay them.

If we must pay, we can at least buy green, raising our rank in the army fighting global warming. We don’t have to buy from SMECO or from BGE, whose power is 95 percent-plus generated from nuclear and/or fossil fuels — coal, natural gas and oil.

Customers of any utility can choose to buy five, 50 or 100 percent of their energy from wind power produced in states like Pennsylvania and Texas, where average wind speeds exceed 12 miles per hour and wind can be harvested on wind farms.

Or you can buy green energy from an energy broker. That’s a whole new category of business inspired by energy deregulation and now, as we all reckon with global warming, coming into its own.

Energy brokers mean deregulation can finally do us consumers some good — if we’re willing to pay more to make a long-term difference in our world’s energy use.

2007: Vol. XV, No. 48 • Michelle Steel

Putting the Wind to Work

Gargantuan turbines aren’t the only way Marylanders make energy out of thin air

Without wind energy, we’re going to have a hard time kicking our fossil-fuel habit.

Maryland’s energy gluttony has left us with a power system that won’t satisfy our burgeoning population or our ravenous appetites for ever-more expensive electricity. Bottlenecks in the power transmission lines could mean blackouts or brownouts before 2011, according to Malcolm Woolf, director of the Maryland Energy Administration.

So the right kind — or scale — of wind power could be a key piece to our energy puzzle.

Wind energy is on the cusp of becoming as huge and widely used as solar power, says Crissy Godfrey, the Energy Administration’s wind expert.

Four-hundred-foot turbines aren’t our only wind option. Other businesses are taking a smaller approach to wind with windmills you could erect on your property or install at your business.

To find out what small wind might mean in Maryland, Bay Weekly shot the breeze with a pioneer who runs his cabin solely on wind power and an entrepreneur who’s outside-the-box wind turbine is actually in a box.

After Bill Autrey built his cabin in Preston County, West Virginia, he decided that vacationing without electricity was a bit too rustic. So he purchased a 50-foot Whisper H 40 for $1,500 and installed it on a sloping hillside about 200 feet from his cabin. Guy-wires steady the pole, and underground wires conduct electricity to storage batteries and to the cabin. The 900-watt system is enough to run his sump pump, fluorescent lights, a ceiling fan and his wife’s hairdryer.

Like Goliath, towering turbines — such as the ones US Wind Force wants to install on two Garrett County mountain ridges within state parks — have the advantage of sheer size and strength. The 400-foot towers generate electricity measured in megawatts that could be sold on the grid system. But like David, small size is an advantage for homes and other individual sites.

Rather than add their power to the grid, small windmills power specific buildings or purposes. Unlike the giants, which typically look alike, small windmills come in three styles: The horizontal version rotates like a pinwheel, as we expect a windmill should. The vertical model spins like a barbershop spiral. The Darius — a European model that hasn’t yet caught on in this continent — looks like a single eggbeater.

With small, individualized energy sources, “You’re taking the future into your own hands in terms of electricity needs,” says Godfrey.

2008: Vol. XVI, No. 11 • Carrie Madren

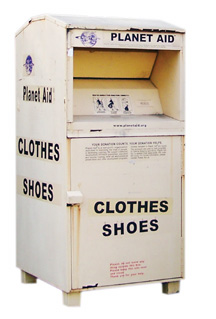

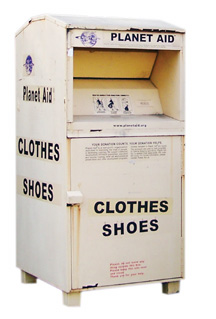

The Yellow Box F⁄ront

Your used clothes are making somebody money; you decide who

On a fall afternoon, traffic whizzes by HB Fuller Wine & Spirits on Bestgate Road, the wind kicking up fallen leaves. A minivan pulls into the parking lot, stopping next to a bright yellow bin marked Planet Aid: Clothes, Shoes. A young man jumps out with a big plastic bag hoisted over his shoulder.

“I live just up the street,” Annapolitan Bill Whitcher says as he tosses the bag of old clothes into the bin’s slot, topping off other bags of sweaters and shirts that have filled the box to its brim. “I chose Planet Aid because it’s convenient, but I don’t know anything about them.”

Whitcher is not the only one taking advantage of the bin’s convenience. Every day, people drop clothing into lately familiar Planet Aid drop-off boxes that get so full “sometimes they overflow onto the ground,” says Betty Fuller, co-owner of the liquor store that hosts this box on Bestgate Road.

The non-profit collects around 250,000 pounds of used clothing and shoes a week from the area stretching from Frederick to Richmond and including Anne Arundel County, Baltimore and Washington, D.C. That amounts to 13 million pounds a year — a staggering total of our old boots, winter coats, outgrown jeans and last season’s heels.

Like Goodwill and Salvation Army, Planet Aid sells your old clothes for profit, using the proceeds for its programs. The strategically placed boxes brought the otherwise little-known organization $20 million in 2006, the most recent figure reported by the Better Business Bureau. The wealth the organization has reaped from our disposable habits puts new life into the saying One man’s trash is another’s treasure.

Convenience is the key to Planet Aid’s success. Throughout our region (except in Calvert County, which is another chapter of our story) Planet Aid boxes abound: in the back of gas stations, at the far ends of run-down shopping centers, in front of small businesses on busy thoroughfares. By making it easy for us to unburden ourselves of our old junk, Planet Aid is making a fortune.

2009: Vol. XVII, No. 45 • Simone Gorrindo?

![]()