50 years on the water; 93 on the land

by Mary Catherine Ball

When we talk about the character of communities - and that's a favorite subject as Anne Arundel and Calvert counties plan for the 21st century - the subject always gets back to people. This week, we inaugurate an occasional series profiling some of the people who bring our communities to life.

We start with Southern Anne Arundel County, where two groups of citizen planners are reaching out as we write to discover the strengths and chart the course of the county's last rural stronghold. Read on and you'll meet three citizens who are noteworthy in themselves as well as types of some of the brightest threads in that region's rich weave:

Old-timer Captain Ed Crandell interviewed on his 93rd birthday;

Pioneer Barbara Sturgell, who came to Deale and made a difference;

Newcomer John Osborne, who's taking a new twist on preserving the region's agricultural tradition.

Captain Ed Crandell of Town Point

50 years on the water; 93 on the land

by Mary Catherine Ball

"He's lived here all of his life. He can remember when they drove covered wagons," Happy Harbor bartender J.R. Hvizda tells me.

She's not quite telling the truth. Captain Edwin P. Crandell missed the covered wagons. But not horse and buggies - or much else.

When he was 14 years old, Captain Ed tells me, his appendix burst. His father visited daily, driving the 20 miles to the hospital in Annapolis in a horse and buggy.

The third generation to live on the family's 99.5-acre property in Town Point, Capt. Ed was born on May 25, 1906 on a point that to this day is one of the prettiest spots in Anne Arundel County.

photos by Mary Catherine Ball Capt. Ed Crandell at 93 still keeps his boat at Town Point Marina, which his son, Ned, at right, has run and owned since Ed retired in 1986.

Town Point Marina sits at the end of windy and sometimes one-lane Leitch Road, off of Deale's Franklin-Gibson Road. On this weekday, life at the marina is quiet and Capt. Ed is painted upon a background of blue, cool water and boats swaying in the wind. His body is lean and Bay-worn; his eyes are searching - whether scanning for familiar faces or, looking past the marina, entering a pool of memories.

I caught up with the captain on his 93rd birthday, as he looked forward to an oyster lunch at Benedict with his son, Edwin M. 'Capt. Ned' Crandell, master of Town Point Marina since his father's retirement in 1986.

"I feel like I'm getting old. I've got arthritis in my knees, and I can't do much walking," Capt. Ed laments.

But don't let him fool you. He is not a man who sits down while life passes him by.

Each morning, Capt. Ed fixes breakfast, and each day he cleans his house. Until three years ago, he kept the yard in top shape, ceasing only when his son insisted.

He wouldn't miss a gathering with the folks from Town Point Marina. Each

year they come together for "little parties, cookouts and crab feasts

when the crabs come on.

"Crabs are so high now, I don't know how anyone can afford to eat 'em," Crandell says, though a handful of crabbers still call his family marina their home port. Prices are only one of the many things that have changed during Crandell's life.

"When I was running parties in here, my dad and I, weren't no more than four or five people taking out parties. Now they're everywhere, Rod 'n' Reel, over the Eastern Shore, up the Bay and down Happy Harbor," Crandell says, laughing.

Fifty years of Crandell's life was spent running fishing parties across the Bay, many of them for Washingtonians from the FBI or universities. "People from uptown didn't do much drinking, but boy could they gamble," Crandell remembers. "They were all nice fellas, but money would be all over the boat."

Crandell took on several other tasks as well. During the war, he worked for the Navy Department in Annapolis. He also farmed and labored as a carpenter.

The Crandells settled in Town Point in 1850. Taking 500 acres under their wing, the family owned milk cows and beef cattle, keeping a herd of steers until eight years ago. Pigs also graced the farm, offering the family fresh ham and ground sausage.

"I think staying here and trying to keep the land that my daddy left me, I think that's about the best thing that I've ever done. I love it here. Not a bit of regrets," Crandell says.

Leaving the water would be near impossible for Capt. Ed. For most of his years, this water served as his means of living. Crabs, oysters and fish were taken from the water and sold to put food on the table for his family.

It gave him pleasure, as well. Capt. Ed laughs as he remembers the steamboats that ventured near Fairhaven shores. Supplies were delivered from Baltimore by water, the fastest way to reach any place in those times.

Remembering this brings back fonder memories of his youth. When the creek froze, he would ice skate, which he claims was one of his greatest skills. Crandell also used his sleigh to cross Tracey's Creek to Deale, which had the only store in the area.

He traveled across the ice in more magnificent style in the Marnita. One of his most memorable boats and creations, the Marnita was his very own iceboat. With skates on the bottom and a sail on top, she took him sailing even in winter.

The winter also brought hard work for the Crandells. They were one of the few families in the area with ice houses on their property. Crandell and his father, Edwin G., carted 55 wagon loads of ice to their icehouse. Freshwater ice, cut off their pond, was saved for drinks. Saltwater ice was cut from the creek for refrigeration. The ice would last the family for the entire summer.

Before World War I, when ice was a summer rarity, even doctors would come to the Crandell homestead, Town Point Farm, for ice when patients were in need.

Until recent years, change came slowly to Town Point, where homes cling to the Bayside while the backside runs through fields to forest. "Up till the '50s if a car came, people [at home] would look out the window," the old captain recalls.

Even now, Town Point is a backwater among marinas, a place people come to get away from it all. And even now, Capt. Ed's home sustains him. "I come down here [to the marina] and enjoy the people," Crandell says.

Which may have something to do with his longevity.

Hvizda thinks she knows the secret behind Crandell's vibrancy: "He's the sweetest man in the world. Never has a bad word to say about anybody. I guess that's what has kept him alive."

Capt. Ed has his own ideas. "I worked hard and it didn't hurt me. I didn't mind working all day and night, sometimes. You need to take care of yourself, though. I have a drink or two every now and then, but I don't abuse myself."

Barbara Sturgell of Happy Harbor

The Anchor of Deale

by Bill Lambrecht

If we could play back the footage of our lives,

Barbara Sturgell would freeze frame at the clip of a girl of 17 gripping

two suitcases as she stands on Pennsylvania Avenue - looking lost. That,

she'd say, was a crossroads.

She had travelled from eastern Tennessee across the Appalachian Mountains on a train that was hurdling her toward her dreams. But first she had to find someone by the name of J. Edgar Hoover.

"Officer, can you point me toward the FBI?" Barbara Hamblin, awash in innocence, asked a policeman.

"Miss, you're standing right in front of it," the officer pointed. "See that sign that says Department of Justice?"

That 1950s' shot of a young woman reporting for her first day of her job is the opening scene, in black and white, of an American odyssey of hard work, strong family and generosity.

A recent shot, in panoramic color, is Barbara Sturgell surrounded by American flags on a perfect Chesapeake Bay morning at Happy Harbor Inn, her restaurant in Deale.

At this moment she's in the midst of a bustling set-up for a Memorial Day weekend. Family is backing her up: daughter Karen, one of five children, a popular bartender and a force at the restaurant, like her mom; son Bobby, a pilot and Naval Academy grad, who is hoisting shrubs and unloading ice at the waterfront restaurant, performing tasks that belie his skills. Three days earlier, Bobby, who trained as a fighter pilot, was ferrying 300 people back and forth to Munich over the north Atlantic in a Boeing 767 jumbo jet.

An early reveler finds Barbara Sturgell, who is momentarily seated at a picnic table on the restaurant dock. "What's the band here this weekend, anyway?" he asks. "Are you going to have the Rolling Stones?"

"That's right," she replies, not missing a beat. "Mick Jagger will be along shortly."

Truth be told, most of Barbara Sturgell's loyal and largely local clientele would rather eat a crabcake than see the Stones or anything foreign. They're happy with their long-neck beers amidst the working boats, content with reliable food that comes in big heaps. They only want change served up in tiny slices.

At landmark Happy Harbor, near the bridge at Route 261 and Rockhold Creek

Road, change doesn't assault. Barbara Sturgell hasn't tried to transform

it into an island paradise or imported a "u" to make it Happy

Harbour. The prices have been kept moderate and the menu down home when

home is on the Bay. One of the regulars complained a few years ago when

they put in new ceiling tiles.

photo M.L. Faunce Family Values: Barbara Sturgell on a catering job with helpers son Bobby, center, and husband Bill.

As a little girl, Barbara Sturgell really did walk five miles to school - a daily exercise that might work wonders today to curb hooliganism in schools. That was back in Claremont, Tenn., where they fought wars over unionizing the mines. Where black lung felled many of the men. And where the mountains could keep a girl from measuring her horizons.

She was the oldest of eight children in a generous, rock-solid family whose values she imported to the shores of Chesapeake Bay. Her mother, Dorothy, taught adult education up until a few weeks before her death last year.

Her mother also knew that her oldest daughter had too much talent and imagination to find happiness in coal country hollows. Barbara's grandfather, Matt, ran a combination theater-restaurant-grocery that hosted stage shows, as they called them. Little Barbara created her own stage, a flat spot at the foot of Jellico Mountain, to put on her own shows with rocks as both props and people.

She skipped two grades and, at age 16, left home for Knoxville to enroll at National Business College, where she would be recruited for work in Hoover's FBI. Soon, at her mother's urging, she would be leaving for Washington and a new life.

"You've got too much ambition and too many dreams to stay around here," her mother told her.

Happy Harbor didn't enter those dreams until the 1980s. Barbara Sturgell had settled in at the FBI as a correspondence typist back before computers and word processors. She met her husband, Bill, who also worked at the FBI, married in 1955 and started a family on High Place in northwest Washington.

Larger-than-life J. Edgar Hoover was known as an iron-fisted FBI head; only after his death was his private life scrutinized. Barbara Sturgell rose to become superintendent of the correspondence section, a trusted position, and had the job of delivering paperwork to Hoover's home on weekends.

"I think he was a great man," she says, recalling how she instructed her employees to work hard when Hoover came around and never to make eye contact with him.

After the births first of Sharon and then of Billy and Bobby, Barbara decided she'd reached another crossroads. She left the FBI, despite a personal letter from Hoover asking her to take three months off and reconsider.

Everybody has their story about how they ended up at the Bay. Bill Sturgell, who had worked in Miami, knew he liked the water, and soon Deale had a new family that would expand further when Karen and Jimmy came along. Barbara Sturgell was doing some book-keeping for Happy Harbor when she became the operating partner of the waterfront restaurant - despite her secret fear of water.

When she was about 10, a rambunctious uncle had tossed her into a swimming hole and told her to swim or perish. She almost did the latter, and to this day, she cares not the least for boating or the water. Bobby Sturgell may or may not be kidding when he says the kids have a plan to bring mom into a bit more harmony with the Bay: swimming lessons.

Anything to keep Barbara Sturgell healthy and hopping would get the vote of just about everyone who knows her. That includes members of her extended family "who come in here every day of their lives," she observes. If they're absent for a couple days, she's been known to get on the phone and find out why.

Barbara Sturgell is known as someone who makes those around her better people, even such notorious locals as the late Tommy 'Muskrat' Greene, the big-bellied, big-hearted Deale character who landed in the Guinness book for his eating vast quantities of oysters on the Happy Harbor dock. He came into Happy Harbor every day and called Barbara Sturgell "mom."

Her benevolence in the community and the region is well-known. You must search to find a charity she doesn't support: American Heart Association; the Cancer Crusade; her Cedar Grove Methodist Church; Deale Volunteer Fire Department; softball teams; lacrosse players; and on and on. She has been PTA president, and her awards include the Gene Hall Community Service Award, which recognizes community contributors in the tradition of the man who once ran Hall's Electric.

Sturgell helps people in ways they know and ways they don't: she gives scholarships and plane tickets to her workers; she 'adopts' families during the Christmas holidays, seeing to it that they have every thing from toys and food to a Christmas tree. She even gave ol' Muskrat - the late-Guiness record holding oyster and snail eater - a VCR. Back in Tennessee, decades after she left, she pays for fresh flowers at her old church every holiday.

Yet Barbara Sturgell is not a preachy sort, especially for a woman with strong views. She's involved in local Republican politics but she supports good Democrats, too, with money and votes. Recently, she's become a behind-the-scenes force in combating what she sees as unwise growth, letting her restaurant become a hatchery for efforts to forestall a widely unwanted supermarket with a plan to develop nearby.

But there are times when you can push somebody too far, even Barbara Sturgell. One such time occurred a few years ago when an Anne Arundel county inspector telephoned with a warning: Happy Harbor had too many signs and banners. They must be removed immediately - or else.

The offensive banners, Sturgell recalls, were two American flags. And if they weren't taken down, the inspector said, the county would see to that Sturgell's liquor license was yanked.

Soft-spoken Barbara Sturgell had a few words for the officious young woman, telling her unmistakably that those two American flags would remain right where they flew. She added the words below that round out a Chesapeake Bay success story, American-style.

"Come back here on Memorial Day," she said, "and you'll see 52 flags flying."

John Osborne of Tracey's Landing

Digging dirt, living and breathing plants, capitalizing

on cactus

by Christopher Heagy

"I dig dirt" - he's not talking physically - exclaims John Osborne, the owner of Chesapeake Plants.

Osborne, 41, is a grower of rare, unusual and exotic plants, the supplier of the fantastic jade plant, cactus displays and Venus flytraps at the New Bay Times Birthday Bash and a man who loves growing plants.

"When people ask me what I do, I tell them, without a doubt, I am a plant man. They are my obsession. I live and breathe plants," Osborne testifies.

Find two brick pillars in Tracey's Landing and your journey begins. Bear right at the tobacco barns and drive until you know you're there. Don't worry. You'll know when you're there.

As your car squeezes past the trees that line the unimproved road that

leads to the greenhouses of Chesapeake Plants, you'll hope you're in the

right place. Once you reach the greenhouses of Chesapeake Plants, you'll

realize you're in a place where life is lived a little differently.

You might think that a man who deals with cactus all day would have a prickly personality. Just the contrary. With his leather fedora and his orangish-red beard, John Osborne looks like a cross between a giant leprechaun and Indiana Jones. But this talkative fellow beams with the excitement and happiness of a man who thoroughly enjoys what he does.

"I haven't worked a day since I've owned this company. I have a good time," Osborne says.

"I make deliveries in Northern Virginia and D.C. I call it the "Land of the Frantic." I've got what these people want. I enjoy my job. I'm never trying to get any place I don't want to go. The most beautiful thing in the world is listening to the morning traffic report walking out my front door and taking my dog Buddy for a walk.

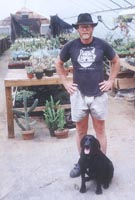

photo by Christopher Heagy John Osborne lives and breathes plants; his dog Buddy does the selling.

"I figure, I'm gonna be dead anyway. I might as well do something I enjoy."

An Annapolis native, Osborne moved as a teenager to Florida, where he developed an interest in tropical plants and began landscaping. His college major in computer science got him a job working in the electronic side of bank security. But he was never happy working with computers. He knew he loved nature and had continued to play with plants, so he decided to follow his passion.

In the 1980s, Osborne left Florida, traveled around the country and eventually settled back in Southern Maryland, which he considers home.

In the mid 1990s, working as a manager in the greenhouse division of Homestead Gardens, Osborne bumped into the opportunity to buy Chesapeake Plants. He jumped at it.

Chesapeake Plants is an exotic plant wholesaler, which, like its owner, does things a little differently. In corporate greenhouses, where many decisions are made by people who aren't even on site, pesticides are sprayed at regular intervals whether they're needed or not. Not in Osborne's greenhouses.

"With a little scouting and cleanliness the use of pesticides can be reduced," Osborne says. "It's just taking the time to look for things and realizing that it is not necessary to spray."

One of his best sources of information, he says, is "little old ladies. They tell me little things about different plants. Their knowledge is infinite. They have years of growing behind them. You can't pay for that. Time is the only thing you can't buy. It's gone."

Osborne sells to garden centers in Frederick, Baltimore, Northern Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District and the Eastern Shore. Unfortunately for us, his plants are not for sale at any garden centers in Anne Arundel or Calvert counties.

"My plants are a unique, high quality product," Osborne explains. "People can grow these plants cheaper, but they can't do it better. Customers may try somebody else, but they always come back."

Last October, John moved his greenhouses from St. Margaret's to his front yard in Tracey's Landing. He's spent much of the past year building his new greenhouses.

"Welcome to the second messiest greenhouse in the world," he jokes. "It might be the messiest but that would be a little embarrassing, so I always go with the second."

Within the year, Osborne plans to have both greenhouses running perfectly. In the next five years, he plans to open a retail garden center in Calvert or Anne Arundel County. He wants to sell unique and interesting plants in this area while continuing to distribute around the region.

"I'm trying to grow, but I'm doing it very slowly. I didn't think it would take this long to build these two greenhouses. I thought I would work and build and work and build. I didn't take time to eat or sleep or go to the bathroom into account."

Business has been good, and Osborne has picked up news accounts. The quality of his plants bring customers back, but the business side is not always his strength.

"I'm a plant dude. I'm not a salesman. My dog, Buddy, does most of the selling," he says. "I take him on deliveries. People come out to the van to see Buddy and wind up buying a bunch of plants. When I don't take Buddy, sometimes they don't even come to the van."

Osborne will sell by appointment - if you can catch him. "When customers come to the greenhouses I feel like they deserve my time to answer questions and talk to them about the plants. But I'm so busy I don't always have the time," he says. "So every now and then I give customers my time, grudgingly."