Promises Kept

Searching for My Grandfather

One year after I graduated from college, I moved to Ecuador to reconstruct my memory of my grandfather. I think I was afraid what might happen if I allowed his memory to be lost.

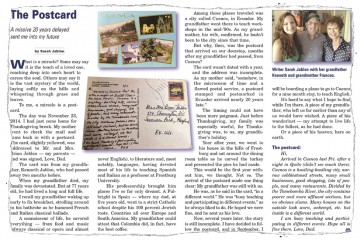

I think maybe he had been afraid, too, when he sent a postcard hurtling through space and time from his own time in Ecuador, where he, a professor at Frostburg State University, went to teach workshops in the mid-’90s. The postcard reached his children back home in Maryland, my parents, 20 years late.

With timing that could not have been more poignant, it arrived two months after his death at age 77. On November 23, 2014, my family was especially woeful, for Thanksgiving was my grandfather’s holiday.

The place in the postcard drew me with the power of an instinct. Like an osprey, I flew to the southern hemisphere in pursuit of a call deep within my bones.

Flying into Ecuador was like passing through a veil. The clouds above the Andes Mountains were thick and endless. Through the veil, we descended into a different world. Canyons and hills were like jagged smiles on the earth. Colors were both subtler, in the landscape, and more vibrant, in the streets and architecture. Culture and language were foreign to me. I was overwhelmed by newness.

From my apartment with big windows overlooking red-tiled roofs, I heard the hustling-bustling city of my grandfather’s words: Cuenca is full of narrow cobblestoned streets, many small businesses, good shopping, lots of people and many restaurants.

Among the sounds of traffic and construction, street dogs barked, children yelled, ¡Mira, mira! and occasionally the theme song of Cuenca rose from gasoline delivery pick-up trucks: Por eso, por eso, por eso te quiero Cuenca. For that is why I love you, Cuenca.

Like my grandfather. I was busy teaching English at many levels, to many ages. I was busy, but not forgetful. When I walked through the narrow cobblestoned streets of El Centro, dating back to the city’s past as a colony of Spain, I saw my grandpa.

I saw him among the many small businesses, good shopping, lots of people and many restaurants. I pictured him on a bench under the towering firs of Parque Calderón. I saw him at every coffee shop patio.

I imagined him, contented and alone, scrawling out a quick message onto the back of a postcard at a café beside the New Cathedral, its three blue domes towering high above him. He’d finish, place a few crisp sucres underneath his empty cup and stroll to the post office. He’d have felt at home amongst the Cuencanos, who walk at snail’s pace.

Like him, in this city where art and culture is so vibrant, I was participating in different events. At a free concert of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in the old cathedral near Parque Calderón, it struck me that I was doing exactly what my grandpa would have done. He drank in classical music like water, never seeming to go a day — not even his last — without it. Closing my eyes, I was in my grandpa’s living room. Hearing the music, I felt him.

Finding My Way

After that concert, I stopped looking for my grandpa. Instead I opened my ears and my eyes to my own experience. I saw, and joined, weekend dancing in the streets. For holidays, parades and the World Cup, the streets shut down. On the biggest holidays, huge wooden effigies are burned in elaborate pyrotechnic displays. During Carnaval, a giant game of tag erupts around the city. Anyone out of doors is fair game to be sprayed with foam or targeted with water balloons from balconies above.

I visited surrounding towns that have preserved their specialty crafts through generations: silver-plated jewelry in Chordeleg; one-of-a-kind, hand-crafted classical guitars in San Bartolomé.

On a high hill of Turi, a city just outside of Cuenca, I swung out over the cityscape into the open air. I visited El Cajas, a national park so high that there are no trees, only countless agave, succulents and grasses. In the lower altitudes of Girón an hour south of Cuenca, I saw waterfalls among the trees.

Looking out onto the rolling hills and ruins of Ingapirca, bathed in the setting sun of the summer solstice, I wondered if the Incas and Cañari stood with this same awe, hundreds of years ago.

They had.

An ellipse, Ingapirca stands atop the hill at the center of a large valley. It was chosen for the alignment of the hilltop to the surrounding mountains by the Cañari. Then the Incas built their Temple of the Sun atop the bones of the former civilization. When the sun shone through the passageway of the Incan moon temple on solstice, it illuminated sacred shrines of both cultures.

In time, Inca culture was swept away by the Spanish. Everything we know about Ingapirca today is a story constructed by the meticulous work by people from my grandparents’ time.

History remains an enigma. It’s up to us, I think, to unearth the bones and carry them in a new light. We are responsible for reconstructing history.

Back home, I measure my changes. My worldview has expanded, filling a void I didn’t know I had. I have earned independence. Overcoming my terror about speaking Spanish gave me new confidence. The bug of wanderlust embedded in my heart, I’m ready for the next adventure.

I’m also ready to tell my story. Here and going forward, I will put those memories to pen and paper. New memories, like all the others, are sloshing around in our brains, slowly and subtly changing form. Even now, as young as I am at 24, I understand these memories are precious.

When I left for Cuenca, I thought I just wanted to tell the story of my grandfather, whose love of languages, people and cultures inspired me. But now that I am back, it’s my own story I want to tell.