Reconciliation

A Mother’s Day story by Jane Elkin

On March 3, 2004, I boarded a plane for New Hampshire to sit vigil at my mother’s deathbed. Waiting at the gate, I wrote this page in my diary. It’s the lyrics to Nella Fantasia (In My Fantasy), a Sarah Brightman song that haunted me for two months and was the last music my mother ever heard, my final gift before singing at her funeral.

I didn’t want to do it, but Mom insisted, and she usually got what she wanted. So I fixed my eyes on a stained glass window and focused on my job — because you can’t sing and cry at the same time.

In my writing, you can see what depression looks like: black, blotchy, and sinking. I remember consciously choosing the marker because it matched my mood that day. Normally, I wrote optimistically rising lines in a fine blue ballpoint. “Keep on the sunny side” was more than a cliché in my life. It was how my mother raised me.

As a toddler, my favorite song was about seven little girls sitting in the back seat, kissing and a-hugging with bread, or so I thought. “Mama, sing Snoopy Eyes,” I would prompt, as in “Keep your snoopy eyes on the road ahead!” Always she complied. It was our special car song. Sometimes I even got a slice of buttered bread sprinkled with sugar.

We had a song for everything. When I couldn’t remember her birthday, she said to remember Alan Sherman’s liverwurst: been there since October 1, and today is the 23rd of May! We climbed Mt. Washington to the theme from The Bridge on the River Kwai. When I started dating, her soundtrack became In My Little Red Book.

I adored her for 13 years and, because of her influence, wanted to be a singer and music teacher. It was all I thought I was good at. But she feared I’d wind up broken, like Billie Holliday or Judy Garland, and she was threatened by anything that didn’t fit her parochial vision for my future. A Catholic education seemed safer than public, so she transferred me without notice from the best performing arts school in the state to the worst. I resented her for months.

That was the first of several dramas in a struggle for autonomy that led me to leave home at 18. Yet I never cut her out of my life, and she never stopped trying to pull my strings. Then she’d go and do something unpredictably wonderful like giving me voice lessons for my 25th birthday. It was complicated.

When I began singing professionally at the nation’s largest Catholic church a decade later, I don’t know which of us was more proud. But by then, her spirituality had turned to fanaticism. When she asserted the point of my vocal studies was “to better praise God,” I wanted to say “No, I do it for my sake, not His,” but I couldn’t.

Her snoopy nose was into everything from my music to my wardrobe, parenting style, even the way I changed a trash bag. Had I known her escalating control and petulant rants were symptomatic of an illness, I might have been more understanding. But by the time she was diagnosed with multiple brain tumors, she had just two months to live, and I was torn between grief and relief.

Her Hand and Mine

After she died, I became a certified handwriting analyst. Applying the method to her journals, I saw that she was motivated by a lifelong fear of abandonment and a midlife loneliness I had never realized. I began writing a book and wound up pursuing a degree in creative writing to do the story justice. But I couldn’t move past my own guilt at never having properly mourned.

“Good writing comes from forgiveness,” my teacher said. “Have you tried looking at your own script?” I had not. I felt sure I knew what I’d been feeling all the time. But there is a difference between being in the moment and reflecting on the moment. What I discovered set me free.

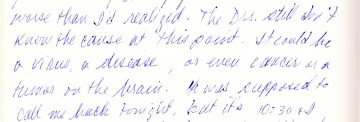

Here is my journal entry from the day I learned of my mother’s illness:

The first thing that struck me was the vertical “rivers” of white space between my words, reflecting a sudden loneliness. It was the same isolation I had seen in my mother’s writing when she was my age. The second surprise was the crashing letters in the right-hand margin, a phenomenon common to suicide notes because the right represents the future. The tendency is subtly evident here in the way the words appear to step off a cliff. Considering what lay ahead, I was literally staring death in the face and shrinking from it.

Final Gifts

Four times I drove home, once with a broken tailbone, and was always surprised at her rapid regression. One weekend she was the adult bibliophile I knew; the next, a giggly teen swooning over movie heartthrobs. I felt privileged to meet my mother ‘pre-me’, even when she resembled a toddler, dangling her feet from an invalid’s pottychair and singing Daisy as my own girls had done.

She liked old hymns, and one day when she no longer could join in, I sang her an original composition. It was my first and had taken years to write. I was nervous about sharing, but still craved her approval and wanted to give one last gift that was uniquely mine. But what if she didn’t like it? It was a bluegrass waltz, and she’d always hated country music.

She listened silently to all three verses, and as the final guitar chord died away, I dared ask her opinion. For once, all she said was “beautiful,” and that was her final gift to me.

Three weeks later, as she lay semi-comatose, I crowned her with my earphones and played Arvo Pärt’s Magnificat and Nella Fantasia, the most heavenly moving-on music I knew. She ahhhed as one sinking into a hot bath, her feet quivering like those of an infant smiling with her whole body.

Within hours her sporadic breathing turned to a death rattle that drove me from the room. I was ashamed of my weakness and kept the baby monitor low that night as I slept in another room, only to be awakened by the grey buzz of its mechanical silence and the fleeting sensation of her presence, which I felt as a slumbering child feels a goodnight kiss.

The purge of beige fluid trickling from her mouth when I found her told me all I needed to know. I closed her wide and vacant eyes, kissed her warm forehead and moved trancelike to the phone where the hospice number was posted in fat black figures. With shaking hands I misdialed three times. Then a voice answered, and I lost mine.

Jane Elkin is a former music teacher, chorister at The Basilica of the National Shrine and co-founder of The Renaissance Singers of Annapolis and Trinitas. She expects to complete her MFA at Bennington Writing Seminars in January.