Sharing the Load

It won’t happen without you.

The actions of federal, state and local governments are just the beginning of revitalizing the Bay. We are also counting on the partnership of millions of people who live in this region to join in protecting the waters that support their health, their environment and their economy.

So said EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson this summer, speaking in her new role as this year’s president of the Chesapeake Bay Executive Council.

But what is expected of you and me in that partnership to protect the waters of Chesapeake Bay?

To answer that question, I’ve sought out a half-dozen people who are living the commitment at home and at work. Read on for their advice on being part of the solution.

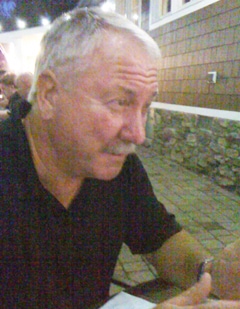

Rich Batiuk

Associate Director for Science: EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program and a Chesapeake Bay Foundation 2011 Lifetime Achievement Conservationist

The problem we’re grappling with is a big one: How to get the 17 million people who live in the Bay watershed to go on a pollution diet.

Not one of us can say we had nothing to do with it. Did you flush your toilet today? Shower? Have a cappuccino? Drive in a car that’s not fully electric powered? Barbecue outside? Put fertilizer on your lawn?

| “The problem we’re grappling with is a big one,” says Rich Batiuk: “How to get the 17 million people who live in the Bay watershed to go on a pollution diet.” |

If you did any of those things, you’re part of the problem — and part of the solution.

We humans tend to care about problems in our back yards — and front yards, too — and that’s good because things we do there in our self-interest also help the Bay.

If you’re a homeowner, start by looking around your property to see how you can manage your piece of watershed more effectively. Getting storm water away from your house and into the ground slowly is the smart thing to do for your property and for the Bay. Rain barrels, rain gardens and French drains all return storm water to use, whether for watering your plants or recharging the water table.

At home, I use a French drain with a curved pipe that takes water from the downspouts underground into PVC pipe pierced with holes and encased in gravel so the storm water drains through slowly. People with shallow wells like ours might eventually drink that water.

If you live in a condo or apartment, you can still be part of the solution. Ask where your storm water goes, into a sediment retention pond or into places it can be reused.

Wherever you live, make your voice heard. Will you buy a low-flush toilet? Recycle your water like you do your newspaper?

Will you join a watershed organization? From the Severn River Association to the Patuxent Riverkeeper, they’re all over Chesapeake Country.

Will you commute by public transportation or hybrid or bicycle, recognizing that what comes out of your tailpipe, nitrous oxide, affects our streams, the Bay and our downwind neighbors?

Ann Fligsten

Coordinator: Growth Action Network of Anne Arundel County; http://growthaction.net/

|

In fighting to save the Bay, Anne Arundel County is Ground Zero. We have one of the longest Chesapeake shorelines, and all our major rivers are listed as impaired. On the other hand, many of the people who live here, as in Calvert County, treasure a quality of life that includes fishing, boating and being in touch with our rivers and the Bay.

Storm water runoff — which each of us has power to affect in our homes and communities — is the biggest source of pollution in this county. So it’s one of the big elements of our Total Maximum Daily Load.

The grassroots group I coordinate, the Growth Action Network of Anne Arundel County, is trying to explain the impact zoning has on our waterways and quality of life through controlling development and storm water runoff.

The once-in-a-decade process of rezoning is under way in the [Anne Arundel] County Council. So right now the Growth Action Network is working with community associations to explain to the Council that making hard-luck exceptions or deviations from approved plans can have tremendous impact on thousands of neighbors and our waterways.

In our homes and communities, we’re practicing what we preach to keep storm water from running down our driveways, onto the streets and into rivers and Bay. The Anne Arundel County Watershed Academy is helping us do that.

Suzanne Etgen

Coordinator: Watershed Stewards Academy

On a residential scale, storm water is the vehicle by which pollutants, such as nutrients and sediment, enter our waterways. Watershed Stewards talk to communities about two categories of action:

|

One: capture and infiltrate stormwater. By using rainscaping techniques such as rain barrels, rain gardens, conservation landscapes and tree plantings, we can slow down, spread out and soak in the storm water that falls on our own property. By infiltration, stormwater is cleaned and cooled before it enters our waterways as groundwater rather than as polluted stormwater. Learn more from the Chesapeake Ecology Center at aawsa.org rainscaping.org.

Two: reduce our personal pollution. Use fewer pollutants in the first place. Pick up and properly dispose of pet waste so its bacteria and nitrogen don’t go into waterways. Care for your lawn in a Bay-friendly way, recycling grass clippings, avoiding pesticides and skipping or limiting fertilizers, using organic.

Reduce energy use. Twenty-five to 30 percent of the nitrogen that reaches the Bay comes by atmospheric deposition because of pollution from power plants, cars and lawn equipment, which contributes much more than cars.

Maintain your septic tank. All tanks should be pumped no less than every three years. If you’re in the Critical Area, think seriously about converting to a nitrogen-reducing system; otherwise, you’re almost certainly contributing nitrogen to our waterways.

Editor’s note: The Academy — a partnership between Anne Arundel County Department of Public Works and Arlington Echo Outdoors Education Center — trains Watershed Stewards to be leaders in their communities. aawsa.org

Steve Kullen

Watershed Planner and Bay Restoration Fund Grant Manager: Calvert County

|

Over 40 years ago our country was dancing to the Carlos Santana tune, You’ve Got to Change Your Evil Ways.

Today that song — at least the title — is so appropriate if we want to see a better environment.

Calvert County — a land mass nearly surrounded by two of the most historical and once richest waterways in the nation — has seen a decline in fin- and shellfish population. Swimming requires a second thought, and sometimes the fish we catch are questionable for consumption. We’ve recently heard of new outbreaks of bacteria, algae blooms and dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay and Patuxent River.

These are all the result of our evil ways.

So let’s work on our evil ways. For many years, Walter Boynton has championed a low-dose nitrogen and sediment diet for our waterways, arguing that the [Patuxent] river could quickly turn around if we cut our pollutants. This is achievable.

Let’s start with septic systems. With 85 percent of Calvert County homes using on-site disposal systems — septic systems — it’s important to understand that nitrogen is one of the leading causes of the decay of our waterways. Reducing our nitrogen load entering the groundwater will result in more available oxygen and a greater life expectancy for residents of the Bay and river.

When the waterways become healthier, we’ll see the growth of fin fish and shellfish, and former watermen (and women) can return to the seafood industry.

More trees! If you live in the Critical Area (that area within 1,000 feet of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries), Calvert County has an outstanding program to help you grow more trees. Calvert will provide and plant the trees at no cost; all you have to do is water and nurse them to maturity. Trees are a natural form of climate control. They provide shade and cooling and help eliminate storm water run-off. Ultimately, trees increase the value of your property. Trees make cents.

Less (or no) fertilizer. Research shows that it is not necessary to fertilize your lawn in the spring — in fact, at all. Fertilizer can wash off of your lawn and enter our waterways, causing more algae blooms that reduce the oxygen in the water.

It’s all about changing our evil ways, baby!

Iain Banks

Personal Transportation and Parking Specialist: City of Annapolis

Could bicycling be the seventh wonder of the world?

Bicycling to work, shops and school reduces automobile traffic and the impacts associated with it, such as climate change and water, air and noise pollution. By bicycling, you help shoulder your part of the Chesapeake’s Total Daily Maximum Load while hearing the sounds of the Bay rather than vehicle noise.

|

It wasn’t so long ago that everyone grew up with a bicycle. Most of my childhood memories involve summer vacation with friends and our bikes.

But for many people, the bicycle gets lost during high school, and the automobile reigns supreme. If that’s happened to you, I suggest that it’s time to increase your awareness of bicycling as an ideal transportation option.

The Annapolis area is perfect for everyday bicycling; the landscape and weather are acceptable for all abilities and all purposes.

What’s more, almost anyone can afford a bicycle. You can get a workable bicycle for $20 at garage sales, Goodwill or your local community bicycle shop.

Promoting bicycling to school might protect our kids from chronic diseases while reducing busing and driving expenses. Many school districts have reduced their school busing services while promoting cycling and walking. Wouldn’t it be good to see more bicycles than cars at soccer practices?

Walter Boynton

Estuarine Ecologist: Chesapeake Biological Laboratory

|

I have two classes of suggestions, and the first has to do with local actions we can take. For example, don’t overfertilize your lawn, and only fertilize at the proper time of the year. One rule to follow is picking the right fertilizer; only brand new lawns need phosphorous, and don’t use more than is recommended. Better still, dig up your lawn and plant native vegetation. Use rain barrels and rain gardens to prevent runoff. If you’re on a septic system, think about converting it to a denitrifying system. Turn down your air conditioning and heat. Recycle as much as possible.

Lifting your part of the load in your own back yard will help, but it is not going to completely fix the Bay.

On the bigger issues — like nitrogen and mercury deposition from power generation; storm water management, nutrient and sediment pollution from agriculture and municipalities; and enforcement — if you want to do something that matters, you need to get active above and beyond what you do at home.

We need to step it up a level. You need to get out and organize. Join a group that advocates for the environment, and insist the leadership be active advocates for the Bay. Make them push their politicians hard.

Get a list of your local, state and federal representatives and write them, saying you want clean water, air and soil. Say you support the Bay Pollution diet and want them to actively support it as well. Implementing the diet will be loaded with conflict. But if you’re not making some people mad, you’re not doing enough.

What Is Total Maximum Daily Load? TMDL, the new buzzronym for Bay cleanup, is short for Total Maximum Daily Load, the measure of the Big Three Bay pollutants — nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment. Nitrogen and phosphorous come Bayward mainly from sewage treatment plants, septic systems, farms and storm water runoff. Storm water helps sediment runoff from all over the land into the water. |