The Art of the Egg

As an American of Ukrainian heritage, Coreen Weilminster cherishes the Easter traditions with which she was raised. Especially when it comes to the ancient art of pysanky, eggs decorated using a wax-resist method similar to batik. In design, in legend and in Christian tradition, these eggs have kept alive a gentle folk art reflecting the Ukrainian nation.

“I grew up in the anthracite region of northeastern Pennsylvania, in a one-horse town called Nesquehoning,” explains Weilminster, 47, of her legacy. “Immigrants flocked to the area just before World War I to work the mines, among them my grandmother’s family.” With them came pysanky.

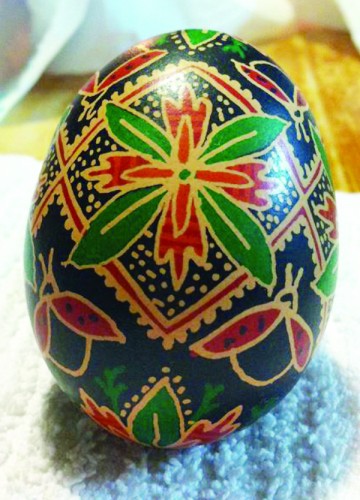

The term pysanka (in its plural form, pysanky) is derived from the Ukrainian words pysaty, meaning to write, and kraska, meaning color. The process is delicate, the product dazzling. A special tool called a kitska — basically, a funnel attached to a stick — is first heated over a candle flame and then filled with beeswax, which quickly melts. Using the molten wax as ink, one writes (as Ukrainians say) a design on a raw egg, then dips the egg in dye. The dying can be repeated in darker colors, each round of wax sealing a different color on the shell. In the final stage, the wax is removed to reveal the finished pysanka.

Weilminster’s grandmother came from a family of 13 children. During the Lenten weeks prior to Easter, three of her sisters (Weilminster’s great-aunts) spent evenings in the kitchen crafting jewel-like pysanky. It was a magical time. From watching these women, Weilminster learned the process. At the age of 16, she was ready. She picked up a kitska and created her first egg.

A pysanky artist was born.

The Power of the Egg

Since pagan times, the tradition of decorating eggs with beeswax and dyes was widespread in Europe, especially among Slavic peoples. Archaeologists have unearthed ceramic decorated eggs in Ukraine dating back to 1,300bce. Many pysanky made today feature motifs adapted from the pottery designs of an ancient tribe of people, the Trypillians, who lived in Eastern Europe from roughly 5,200 to 3,500bce. References to pysanky abound in their art, poetry, music and folklore.

Trypillians led peaceful lives as farmers and artisans. Like most early humans, they worshipped the sun as the source of all life. In the land that is now Ukraine, eggs decorated with symbols from nature became central to spring rituals and sun-worship ceremonies. The logic was simple. The yolk of an egg symbolized the sun and its white the moon. In winter, the landscape appears lifeless, as does an egg. As an egg hatches a living thing, so the sun awakens dormant fields in spring. Thus the egg was considered a benevolent talisman with magical powers, able to protect and bring good fortune.

Legend says the first pysanky came from the sky. A bitter winter had swept across the land before migrating birds were able to fly southward. They began to fall to the ground and were in danger of freezing. The peasants gathered the birds, brought them into their homes and nurtured them throughout the winter. Come spring, the peasants set the birds free. The birds returned bearing pysanky as gifts for the humans who saved their lives.

In early Ukraine, a veil of superstition enshrouded pysanky. They protected from fire, lightning, illness and the evil eye. To ensure a good crop, a farmer coated an egg in green oats and buried it in his field. For a good harvest of honey, he placed eggs beneath his beehives. For a plentiful fruit harvest, he hung blown eggs in his orchards and in trees surrounding his home. When building a new home, he marked its corners with eggs, then buried them in the ground as a form of protection.

“An early legend said the fate of the world hinged upon pysanky,” Weilminster says. “Evil, in the guise of a monster was kept chained to a cliff. Each year in the spring, the foul creature sent his minions to encircle the globe and tally up the number of pysanky made. If the count was low, the creature’s bonds would be loosened, unleashing all manner of evils.”

Writing in Symbols

At the root of all pysanky is symbolism. Every color, every symbol has meaning, many echoing pagan respect for nature and life. Late in the 10th century ce, however, their interpretation changed as Christianity gained acceptance in Ukraine. Ancient pagan motifs and Christian elements blended. Pysanky lost their connection to sun worship. Once tied to the sun god Dazhboh, motifs featuring the sun, star, cross and horse came to represent the Christian God. Grapes, a harvest motif, came to represent the growing Church and the wine of communion. The fish, formerly a mystical action figure, came to symbolize Christ. Triangles that signified the trinities of air, fire and water or the heavens, earth and air now honor the Holy Trinity.

Still, lurking behind the Christian symbolism are traces of magical thinking. Take, as an example, the 19th and 20th century burial customs observed in Christian families when a child died during the Easter season. For food to eat and a toy to play with, the child was buried with pysanky. Even today, lines written on pysanky should remain unbroken so as to not break the thread of life.

Keeping the Tradition Alive

As the most important religious holiday in Ukraine is Easter, pysanky has become linked with its observance. With the arrival of the Lenten season, the women in traditional Russian Orthodox families often get down to waxing.

As a wife, mother, professional and pysanky artist, Coreen Weilminster has come a distance from her Pennsylvania roots. Living in Arnold, she enjoys the Chesapeake life with husband Eric and their two teenage daughters, Brooke and Braelyn. On weekdays, she works in Annapolis, coordinating educational programs for the Chesapeake Bay National Research Reserve in Maryland. Somehow, though, on evenings and weekends, she finds time for pysanky. Now with 31 years of pysanky experience, she happily shares her love of the craft with others, teaching workshops in her home and at the Jug Bay Center Wetlands Sanctuary in Lothian.

At this year’s Jug Bay workshop in late February, Weilminster spoke with nostalgia about her family’s mystical late-night egg decorating sessions.

“In the weeks before Easter, my great-aunts Helen, Irene and Elizabeth began making pysanky by the dozen,” she said.

Attention was paid to color, rhythm, symbolism, harmony and the unwritten rules of technique.

By Ukrainian tradition, making pysanky is a holy ritual for the women of the family. No one else is supposed to peek. After the children are put to bed in the evening, the fun begins.

“In pagan days, the pysanka was considered a vessel. It held life,” said Weilminster. “Even today, the purpose of making pysanky is to transfer goodness from one’s household into the designs. You’re to put an intention into your eggs and then give them away as gifts. We gave them to celebrate births, weddings, funerals and religious holidays. Especially on Easter Sunday.”

As members of a Russian Orthodox congregation, Weilminster’s family observed all the old Easter traditions.

“On Easter morning, we brought the food for our Easter feast to the church for the Blessing of the Baskets,” Weilminster recalls. “We’d line a basket with hand-stitched towels. In went pysanky, ham, horseradish, butter molded into the shape of a lamb and a loaf of Paska bread, a yeast bread enriched with eggs and melted butter. Pussy willows might be tossed in for effect.”

Back stood the parishioners as the priest and altar boys made a joyous procession. The priest sprinkled holy water and blessed the baskets.

“It was impressive. But all I wanted was the ham in that basket,” sighs Weilminster.

The Moment of Truth

When the class got down to business, Weilminster instructed on waxing and using the aniline dyes she had mixed — all while reminding her students to be forgiving of themselves.

“Keep in mind that this takes time and practice. Your egg will look like it’s your first egg,” she said. “It is. Still, when the wax is removed, I promise you, you’ll love it.”

At first, students worked in silent focus. Gradually, confidence grew. At the end of the waxing and dyeing process, Weilminster helped each student blow the egg out of its shell. Then came wax removal.

“Traditionally, wax was removed by holding the egg over a candle flame,” Weilminster said. “Me, I believe in modern hacks. I use the microwave.”

Loud squeals emanated from the kitchen as one anxious student after another wiped the softened wax off their pysanky. All he or she wanted to do was make one more, and another after that.

That’s the way it’s supposed to be.