The Life — and Afterlife — of a Chesapeake Legend

The Trumpy yacht Counterpoint waited dry-docked at Herrington Harbor North for the right person to come along and shine her up, clean her decks and splash her into the water again. That person would have to match the dedication and vision of her former owner, William Watkins, who passed away in 2015.

As wooden boat enthusiasts know, caring for a ship like this is equal parts passion, grueling work and money. They agree, nonetheless, that wooden boats deserve a second chance at life. Not all can be returned to their original state, but all deserve to be repurposed and reimagined to earn a new kind of glory.

Wooden boats seem to have a soul, a passion of their own that infects their keepers. Maybe it’s the way the hull groans and hums when it races through changing waters. Maybe it’s the satisfaction of seeing the clouds reflected in a perfectly varnished piece of teak. Whatever it is, wooden boats embody nostalgia.

With their unmistakable flared bows that gently pull the water away from the boat as they glide along the Bay, Trumpy yachts are remarkable examples of desire for another time. Or, in the case of the Watkins family and Counterpoint, more time.

Another Time

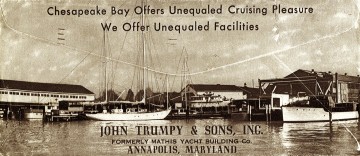

John J. Trumpy & Sons moved from Gloucester City, N.J., to Annapolis in 1947. The Trumpy yacht yard sat where Charthouse Restaurant now serves its fare on Second Street in the Eastport neighborhood of Annapolis.

Originally built for Francis V. DuPont in 1948, Counterpoint featured the flared bow of Trumpy yachts that allowed for a smoother ride through choppy waters. Its double-hull construction promised both longevity and durability. Teak decking and mahogany planking combined with brass hardware and chrome instruments made this stylish boat fit for the family that commissioned it and a worthy dream for a lover of the Bay.

Eventually the 58-foot yacht was purchased by William Watkins, a Marylander whose life always seemed to lead him back to the water. As a young boy, Watkins would head down to the Colchester section of Baltimore and watch the ships.

At 17, Watkins convinced his parents to let him join the Navy. In World War II’s Pacific theater, he served on the destroyer escort Abercrombie, which provided support during attacks on the Philippines and Okinawa.

Returning from the war, Watkins went on to be a mariner for Standard Oil. Later he owned the Forest Inn in Reisterstown, a restaurant renowned for its crab cakes. Patrons could charter the restaurant’s boat, Freedom II. This 46-foot fishing boat with central air soon became a favorite of industry leaders in East Baltimore and reinvigorated Watkins’ passion for being on the water.

Soul Mate

Counterpoint joined Watkins’s small fleet in 1974. Berthing her at the Trumpy yacht house in Annapolis, he managed to keep the purchase a secret from his wife for nearly two years, before Charlie Satchell, who ran the boathouse, let the truth slip during a phone call. When Watkins’ wife Barbara answered and denied that the boat was theirs, the jig was up.

“Counterpoint was his mistress,” explained son Scott Watkins in a phone interview. “She was representative of a time when things were done with style and beauty and had a story. Boats have a soul, and she was my father’s soulmate.”

Diagnosed with leukemia, Barbara died when she was 43. Her passing left Watkins responsible for the restaurant and raising the kids. Counterpoint became a refuge.

As the years passed, time took its toll on boat and owner. Watkins continued to work on the boat for as long as he was able, but when the maintenance grew too difficult and costly, Watkins decided to haul the boat out, still holding on to the hope that he — or someone — might restore her.

Counterpoint was towed from her berth with her 83-year-old master on a misty, bitter March morning in 2012. “It was like seeing two old institutions,” Scott said, “sailing for the last time together.” It took nearly 24 hours to deliver the boat to its new home at Herrington Harbour North Marina.

Watkins died in 2015 at the age of 85. Counterpoint decayed in place.

“Over the years, the Watkins family and Herrington Harbour North pursued virtually every avenue to find someone who wanted to restore Counterpoint,” said Herrington’s Hamilton Chaney.

One More Time

Salvage became the best and, Chaney says, “the only option to save a part of this important piece of maritime history.”

Piece by piece, Watkins’ Counterpoint has been dismantled. Thus far, nearly all of the mahogany planking from the hull’s stern and starboard has been salvaged as well as 25 pounds of screws, two five-blade propellers, both rudders and a companionway in need of a little cleaning.

“It’s a good compromise,” said Scott Watkins of the fate of his father’s beloved Counterpoint. “Boats like her are a representation of the soul and history of the region. It’s so necessary that they aren’t forgotten.”