The Secret Treasure

You’d want to know if you were neighbor to a secret treasure of masterpieces.

So I’m telling you.

Sixty-three paintings by great Northern European masters — Jan Breughel, Rubens and Van Dyck among them — lived quietly in Annapolis for two years, and Prince George’s County for 16 more years.

“There was no collection of old master paintings remotely like it in this country,” says Arthur Wheelock curator of northern baroque paintings at the National Gallery of Art. “In fact, in both quality and quantity, no collection of Flemish art in this country would rival it until late in the 20th century.”

They were here, and then they were gone.

What were they doing here?

Where are they now? That’s the mystery that obsesses Susan Pearl.

On the Run

To unravel that mystery, return in time to 1794, when the newly independent United States of America was a safer haven than war-tossed Europe.

As ripples from the French revolution threatened Antwerp, art collector Henri Stier fled.

“He got the paintings and his family out,” recounts historian Pearl.

By horse and carriage and by sailing ship, family and the art collected by Steir’s grandfather-in-law, Michel Peeters, traveled: 63 paintings protected in heavy wooden crates.

At the core of the collection were, Wheelock says, “masterpieces by Flemish artists, although it also included paintings by, among others, Jacob van Ruysdael, Rembrandt, Titian and Tintoretto. The collection contained no fewer than 10 paintings by Rubens and six by Van Dyck.”

The displaced Belgian family and their paintings took up residence for two years in Annapolis, renting the William Paca House.

At the time “there was good society here, very fashionable, with lots of parties,” says Historic Annapolis curator of collections Pandora Hess. Henri Stier’s young daughter Rosalie and George Calvert met and married there.

But the paintings remained a secret treasure.

Hidden in the New World

Stier, an aristocrat who owned three homes in Belgium, had landed ambitions in the New World. He bought 800 acres in the Anacostia watershed, near the port town of Bladensburg. But before his house was finished, he was back in Belgium. In 1803, Riversdale became the home of Henri’s daughter Rosalie and her husband George Calvert, of Maryland’s founding family. The plantation gained renown, but not the paintings. They remained a family secret.

From 1794 to 1816, the paintings stayed crated, lifted out only to be wiped clean of mold, shown to just a few artists. Only a few of the smaller paintings were hanging in one parlor and seen by visitors.

Nobody saw them. Nobody enjoyed them.

Then Napoleon met his Waterloo, and Europe was again safe.

Send the paintings home, Henri wrote his daughter in December 1815. His letter traveled by ship. She received it in February. Ever dutiful, she planned their journey home.

They’d have left unseen were it not for the pleas of American painters Rembrandt Peale and Gilbert Stuart. At Paca House and Riversdale to paint the family, they’d had peeks at the paintings. Peale wrote that Stier “had placed before me three excellent portraits, by Titian, Rubens and Van Dyck, as objects of inspiration for a young artist.”

Convinced by these artists “that it would be a public wrong that such a collection of pictures — the like of which had never been in America — should pass out of the country entirely unenjoyed,” George and Rosalie Calvert opened their house. In the spring of 1816, Washington society mingled with artists and collectors at the first blockbuster art exhibit in this country.

“Some of the finest paintings ever in America,” they were called by Sarah Gales Seaton, wife of the co-editor of the National Intelligencer.

On June 2, 1816, the paintings were again crated to repeat their journey by horse-drawn carriage, then by ship from Baltimore to Antwerp.

They crossed the Atlantic a second time aboard the sailing ship Oscar, subject to tempest, predation and shipwreck.

They survived the crossing. What became of them then?

Tracking the 63 keeps Pearl busy.

The Wide World Over

Pearl’s quest began in her office. She worked upstairs in the mansion before it was restored as Riversdale House Museum. Her job — researching historic structures for Maryland–National Capital Park and Planning Commission — bumped her into the secret treasure.

Original letters and papers told her part of the story. The more she learned, the more she wanted to know.

What had become of them? Where were they now?

“Finally, I hit the gold mine,” she told me. A genealogist hired by Henri Stier’s fifth-generation descendants shared copies of the “masses of letters” back and forth across the Atlantic.

With letters, a sketchy packing list — written as family hastened to escape French armies in 1794 — and a catalogue of sales, she set about tracing their post-American journeys.

Art is long; life is short. The owners died, but the paintings thrived, increasing in value with age.

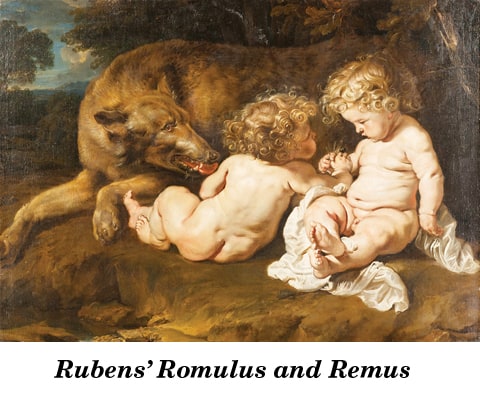

Each owner’s death led to an auction that disbursed the paintings more widely. At their sale in 1817, Henri Stier bought his 20 favorites from the collection that had been at Riversdale. His death in 1821 returned one painting to Riversdale. George Calvert — widower of Rosalie, who died three months before her father — purchased Rubens’ Romulus and Remus. That painting crossed the Atlantic a third time.

Cross-checking list after list with the original packing manifesto, Pearl has successfully traced 20 of the 63 paintings that had long ago found refuge in Chesapeake Country. They are the most prominent and valuable ones, mostly kept in the family.

“I find it amazing how much information about that collection one can pull together from the packing list, Rembrandt Peale’s account and descriptions of the works in subsequent sales,” Wheelock said.

Romulus and Remus continued in the American Stiers’ family and is now in the keeping of the North Carolina Museum of Art.

Two more are in America: Rubens’ painting of his brother Philippe in the Detroit Institute of Art and Jan Brueghel’s wonderful The Entry of the Animals into Noah’s Ark in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

The Van Dyck portraits of Philippe LeRoy and his bride Marie de Raet hang in the Wallace Collection in London.

At the outbreak of World War II, several paintings owned by the European branch of the family found sanctuary in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, where they remain.

Pearl has seen almost all 20.

“Twenty out of 63 doesn’t sound like a lot,” Pearl says, “but it actually is, considering what you have to do to track them down.”

As for the others, she says, “I’ll probably be working on it for the rest of my life.”

See for Yourself

Here it is 2016, the bicentennial of Michel Peeters’ collection’s departure from America.

And here they are, 16 of the found paintings of the original 63, on exhibit again at Riversdale.

“Of course we couldn’t get the originals,” Pearl admits.

Masterpieces are not loaned to county museums with neither security nor ideal air and lighting conditions. Instead the museum purchased high-resolution digital images that, printed and framed locally, now hang throughout the Riversdale House Museum.

“The exhibit is a wonderful way to step back in time, envision the original paintings and feel the excitement visitors experienced when world-class Old Master paintings were publicly displayed in Riversdale Mansion in the spring of 1816,” said Carol Benson, director of Anne Arundel County’s Four Rivers Heritage Area.

Docents lead tours, “electronically enhanced” with hand-held tablets that interpret and enlarge paintings for inspection of detail (though connections are temperamental).

It’s a sight worth seeing, especially now that you know the story.

Open Friday and Sunday 12:15-3:15pm thru Oct. 23. (On Sunday, Sept. 18, a University of Maryland quintet plays Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition): $5 w/age discounts: 301-864-0420; [email protected].

Copies of the Stier-Calvert correspondence are held in the Riversdale Historical Society archives.