The Uncertain Future of Handwriting

Can you sign your name in cursive?

For much of American history, handwriting was a hallmark of education and character, taught in classrooms as part of the triumvirate of reading, ’riting and ’rithmatic. Students who persevered through eight grades took as much pride in their penmanship as John Hancock, whose graceful cursive on the Declaration of Independence made his name a synonym for signature, as in sign your John Hancock on the dotted line.

Into the 20th century, handwriting was so foundational a part of the public school curriculum that educators devoted themselves to perfecting a system good for one and all, just as modern educators have with Common Core. From letterforms and linkages standardized in the mid-1800s by bookseller and abolitionist Platt Rogers Spencer — and not so different from many Hancock used — the American cursive handwriting style evolved.

Spencerian descendants — about whom we’ll have more to say — were so successful that by the mid-20th century, Americans from coast to coast could write — and read — one another’s handwriting, as well as John Hancock’s.

Yet just about then (does Sputnik ring a bell?) states began de-emphasizing handwriting to allow more classroom time for the curriculum we know today as STEM.

Does cursive have a future? That’s the question we ask in honor of National Handwriting Day, which falls on January 23, the birthday of the Massachusetts’ patriot John Hancock. No longer can every graduate of our public schools read Hancock’s signature — or, for that matter, the handwritten document itself.

Can you?

A Pillar of Civilization

Through the four- or five-thousand-year span of recorded history, handwriting has evolved, influenced and reflected every aspect of culture. This art of forming visible, readable characters has evolved in many styles, from cuneiform and hieroglyphics to unconnected block letters to flowing cursive.

About the time the Egyptians were developing hieroglyphics, Sumerian merchants were codifying their transactions into cuneiform script. Ever since, handwritten documents have recorded births, marriages and deaths but also started and ended wars. They’ve bought and sold land and slaves, and guaranteed — or challenged — our voting rights.

By about 1500 BCE, the Phoenicians had an alphabet of 22 phonetic symbols. This marvelous invention spread to Greece, Persia, India and Egypt.

Like any new technology, handwriting brought on tidal waves of change. Socrates feared a written language would destroy memory, according to Anne Trubek, author of The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting. To a degree, he was right; the old oral tradition that gave rise to Homer is obsolete. On the other hand, as French philosopher Jacques Derrida noted, we only know what Socrates thought about anything because someone recorded his ideas.

In the second century BCE, the Roman Empire conquered Greece, adopting its then 23-letter alphabet. The alphabet spread throughout the Roman empire. More letters were adopted over the centuries until, by the 15th century, the Roman alphabet consisted of 26 letters.

By then, handwriting had become a specialized skill, practiced by the scribes and monks who saw their livelihood threatened when Gutenberg developed a printing press capable of assembly line-style production of books. Despite their worries, handwriting remained for many centuries the dominant medium for recording and sharing information.

The Renaissance development of copperplate engraving brought the fanciful flourishes to script writing. This script evolved into the italics from which cursive and basic lowercase letters derive.

In early America — as in so many cultures over the millennia — handwriting was a skill that could earn a craftsman a living. By the 1700s, master clerks were doing the actual penning of many of our historic documents. The United States Constitution was drafted by James Madison, penned by Jacob Shallus, assistant clerk of the Pennsylvania State Assembly and signed, more or less elegantly, by 56 colonial gentlemen, for whom fine handwriting was a mark of education and cultivation.

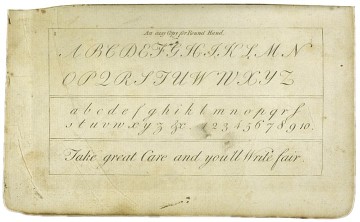

In 1786, George Fisher published The Instructor, or American Young Man’s Best Companion Containing Spelling, Reading, Writing, and Arithmetick.

“The capitals must bear the same Proportion one to another,” wrote Fisher. He directed that upstrokes be fine, and downward strokes fuller and blacker. “And when you are in Joining,” he instructed, “take not off the Pen in writing, especially in running or mixed hands.” His words may ring familiar to 60- and 70-somethings who learned Palmer cursive in school.

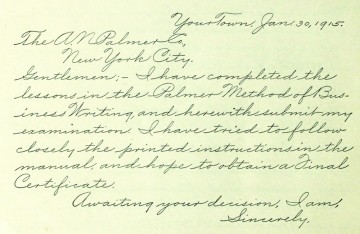

In the mid-18th century Platt Rogers Spencer developed a utilitarian writing system uniting aspects of several popular writing systems. During the late 1880s, the Spencerian method evolved into the Palmer system, which emphasized writing with arm movements rather than with the fingers. With variants, Palmer remained the school standard of penmanship through the 1950s.

Meanwhile, other technologies were changing the world. As early as 1947, when TIME magazine was already bemoaning the “day of typewriters, shorthand, telephones and Dictaphones,” educators and the media were complaining that schools were neglecting penmanship instruction. In 1955, the Saturday Evening Post pronounced us a “nation of scrawlers.” By the 1980s, some public school students were receiving little or no formal handwriting training.

Cursive Uncommon in Common Core

Since 2010, to many teens and young graduates of Maryland’s public schools, the swirls and twirls of cursive are as unreadable as ancient Sanskrit.

Trace it back to Maryland’s adoption that year of Common Core State Standards in reading, English/Language Arts and mathematics, known

as the Maryland College and Career-Ready Standards. Later, pre-K standards were added.

State education standards have been around since the early 1990s, varying from state to state. In 2009, most states, the District of Columbia and a couple of territories voted to develop Common Core State Standards. Maryland was among the first of many states to adopt the new, voluntary standards.

Common Core put our nation “one step closer,” said Bill Gates, co-chair of the Gates Foundation that bankrolled the initiative, “to supporting effective teaching in every classroom, charting a path to college and careers for all students.”

Often Common Core pushed cursive aside for keyboarding and computer skills, math and sciences.

How Important are Connected Letters?

Does the loss of our common heritage of handwriting matter? Opinions are divided.

Juli Folk, 37, is reading handwritten Calvert County Census documents for the Center for the Study of the Legacy of Slavery at the Maryland Archives while studying for her masters degree in Library Information Science at the University of Maryland ISchool.

Her volunteer project depends on her ability to read cursive in many hands over many decades. “I had fun learning it in elementary school,” she says.

Yet for today’s students, she’d be happy to see it “offered as an art class. Or teachers could show students what cursive letters look like, then let them learn it on their own.”

“What matters,” she says, “is that handwriting, whether printed or cursive, is legible.”

The American Bar Association seems to agree. Printed signatures are just as legal as are cursive — or electronic ones,” according to University of Missouri law professor David English.

Other benefits may make cursive fit enough to survive the keyboard era.

Some researchers say learning cursive benefits brain development and fine motor skills in children, leading to improved writing skills and reading comprehension — skills critical across the Common Core.

Dr. William R. Klemm, senior professor of neuroscience at Texas A&M, says learning cursive helps train the brain to function more effectively, increasing hand-eye coordination and reading speed. Thus, he concludes that schools that drop cursive are depriving students of an important developmental tool.

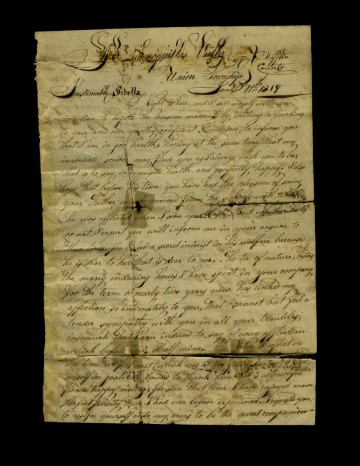

Whatever learning cursive may do for our hands, eyes and brains, losing it certainly cuts us off from our past. A generation illiterate in cursive will be unable to read historic documents, including Grandma’s letters.

“Sending a handwritten letter is becoming such an anomaly,” says actor Steve Carell. “My mom is the only one who still writes me letters. There’s something visceral about opening a letter. I see her in handwriting.”

At the Maryland State Archives, Emily Oland Squires hears complaints from researchers, especially students, struggling to read with cursive.

Archives staff tries to bridge the gap by helping research teachers create lesson plans that include both primary source documents written in cursive and their transcriptions. Online transcriptions have been made of many documents pertaining to state and African American history.

“Still, we ask teachers to let students try to work from the manuscripts before giving them transcriptions,” says Squires. “It helps them learn.”

Does Cursive Have a Future?

Some states have legislated a future for cursive. In 2016, Alabama and Louisiana — not states earning top educational ratings — became the latest of 14 states that now require cursive in school.

Maryland does not require cursive be taught.

“There are currently no standards for cursive,” says Walter Lee, of the office of the Curriculum Coordinator and Instruction at Anne Arundel County Public Schools. “But Maryland created a framework in which cursive does appear.”

Lee explains that Maryland decided to include cursive as part of the framework for interpreting the state standards for the Commonwealth of Maryland. “There are no policies governing cursive,” he says, “but there are practices. It is up to local education agencies.”

In Anne Arundel County, he says “incorporating cursive into reading time during the school day is a school-based decision, meaning that it is up to the principal.”

In the bigger picture, it may be, as Trubek says, that the decline in our use of handwriting in our daily lives is only the next stage in the evolution of communication. Where we’ll be next, who knows.

While we wait to see what the next wave of change brings, we might all heed the advice of Benjamin Franklin: “Either write something worth reading or do something worth writing.” He did both.

In honor of National Handwriting Day, pick up a pen or pencil and put it to use.