Touring Black History

For Americans of African descent, the rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness have not been unalienable. Yet Maryland’s first black, Mathias de Sousa, reached our shores in 1634 on the Arc, not on a slave ship. An indentured servant, de Sousa earned his freedom in four years. Meet him — and generations who sought self-determination in America — on Bay Weekly’s Black History tour of Chesapeake Country.

-Sandra Olivetti Martin

Annapolis

Gather Inspiration at Banneker Douglass Museum

Banneker Douglass is a state museum that’s entirely of the African American experience. The original space was built and consecrated as Mount Moriah African Methodist Episcopal Church. Namesake Frederick Douglass attended the dedication in 1874. When the congregation moved to larger space a century later, African Americans and preservationists succeeded in making it a museum.

It still feels like a dedicated space, and it takes a very personal approach to history. You’ll get a greeting and a bit of orientation as you enter. Upstairs in the annex is the permanent exhibit Deep Roots, Rising Water. Start there, seeing the skyline of Annapolis as if by ship. Enter and encounter people (very nice almost life-sized cutouts) who lived African American history, from slavery through adversity to triumph — including the first and second black explorers to reach the North Pole.

Art as well as history helps this museum interpret the African American experience. Now showing are two visionary exhibits. Downstairs, see Maryland state photographer Jay L. Baker’s brilliant shots of 21st century Ghana, including a one-room school. Upstairs in the church sanctuary, Baltimore mosaic artist Loring Cornish uses glass, the wrought iron frames of Rashaud Williams and lots of shoes to interpret the theme In Each Other’s Shoes.

84 Franklin St., Annapolis, 410-216-6180; www.bdmuseum.com. Tu-Sa 10am-4pm, free.

–SOM

The William H. Butler House

Right next to City Hall, a handsome three-story, brick home is easy to walk by with no more than a glance. Who’d know it was the home of William H. Butler, prosperous 19th century African American man of business and civic affairs?

Historians Jane McWilliams and Janice Hayes-Williams would.

McWilliams, author of Annapolis, City on the Severn: A History, advises you to pause here and reflect.

“Maryland’s 1864 Constitution made everyone free,” McWilliams says. “We’ve had 150 years since slavery, and those years need to be remembered, too, for the tremendous strides black men and women made.”

The black owner of this house, William Butler, personified capability. Born into slavery in Anne Arundel County, he became carpenter and landowner; trustee of the city’s first school for black children, Stanton School; and the city’s first black elected to public office, as alderman, in 1873.

148 Duke of Gloucester St., Annapolis.

–SOM

Sit with Alex Haley at City Dock

You won’t find a more inviting place to sit down with black history than the Alex Haley-Kunta Kinte Memorial. The four bronze figures have been City Dock citizens since 1999. There’s more to the memorial, however, and it makes an inspiring albeit brief walk.

First, who are these people?

Alex Haley, who was not a Marylander, broke the nation’s long silence on slavery in his legendary Roots book and television histories. African American, European American and Asian American in descent, the kids listen spellbound to the resonant story of how Haley traced his roots to Kunta Kinte and this very spot in Annapolis.

The theme continues in story wall along Compromise Street. Ten bronze plaques, each framed in low-relief illustration, pair a Roots quote with a message written by poet Maya Angelou. Their subjects are dedication, heritage, servitude, perseverance, faith, family, forgiveness, love, challenge and diversity.

–SOM

Visit the Poles of Segregation at the Maryland Capitol

Thurgood Marshall strode onto Lawyers Mall in 1996. The first black associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court was, by then, three years dead and a hero of the civil rights movement. Yet it’s a young Marshall who stands in bronze on this granite pedestal, about the age of the Marshall who brought down school segregation in the courts.

Three other bronze figures are with him. The two children seated on a nearby granite bench represent all the black schoolchildren whose segregated education ended with the young Marshall’s Supreme Court victory in Brown vs. Board of Education.

Nearby stands a bronzed Donald Gaines Murray, in whose name Marshall won the integration of the University of Maryland.

What looks like a monument to success is really a counterpoint in opposition. Marshall’s opposite, honored at the Capitol for 140 years, is former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Roger Brooke Taney.

Taney, whose bronze image sits cloaked in judicial robes moldering with tarnish, ruled in the Dred Scott case that the U.S. government couldn’t forbid slavery and couldn’t free slaves.

The sculptures of the two Maryland jurists who served on the U.S. Supreme Court a century apart — and who were a spectrum apart in philosophy — flank opposite sides of the State House.

–SOM

Anne Arundel County

Remember Rosenwald Schools

Julius Rosenwald knew what it was like to be set aside as separate. He was the son of German-Jewish immigrants who came to the Land of the Free to live their dreams.

By 1912, Rosenwald had amassed a fortune as the head of Sears, Roebuck and Co. and wanted to share his wealth with America’s separate and unequal population.

On his 50th birthday, the philanthropist donated $25,000 to Booker T. Washington’ Tuskegee Institute for teacher training. When Washington found a $2,800 surplus, he asked Rosenwald if he could use the money to build one-room schoolhouses for rural black communities.

The idea took off. By 1919 The Tuskegee Institute could no longer meet demand. From 1912 to 1948, the Julius Rosenwald Fund spent $70 million building 4,777 schools and funding scholarships throughout 15 southern states, including Maryland.

One hundred years later, Rosenwald schools have gone the way of segregation, but the bones of 155 schools built in Maryland — including 22 in Anne Arundel and five in Calvert — serve as reminders that education was an early stop on the road to self-determination.

Learn more about the schools in your community, view pictures and see how much each structure cost, at: http://rosenwald.fisk.edu.

–Diana Beechener

Calvert County

Enter History in The Old Wallville School

The voices of teacher and her students would have filled the small space of one-room Wallville School, one of Calvert County’s earliest for African Americans. In 1880, parents and neighbors built the school on Mackall Road about a mile north of today’s Jefferson Patterson Park.

Older students came early each day to stoke the fire and to fill a bucket with drinking water. Students grades one through seven sat three to a desk and wrote on logs with leveled tops. Pencils were broken in half for two children, and worn-out textbooks were passed down from the white schools.

Abandoned in 1934 because it was too small, the neglected building was succumbing to nature. In 2004, the community group Friends of the Old Wallville School rescued, restored and resituated the old school on the grounds of Calvert Elementary School.

“It’s a piece of tangible history that informs our view of the present and future,” says Harry Wedewer, Friends president. “There are so many themes wrapped up in the school.”

Wedewer tells more of the story of the Old Wallville School on Tuesday, Feb. 28 at 7pm at Calvert Library, Prince Frederick: 410-535-0291.

1450 East Dares Beach Rd., Prince Frederick, 410-474-3868, www.oldwallvilleschool.org.

–Sandra Lee Anderson

Oyster Packers at work: Lore and Sons Packing House

“When you shuck oysters, see, I say you’re your own boss, you can work when you feel like it,” explained Audrey Bishop. An unexpected comment, but after World War II, shuckers at the J.C. Lore and Sons Packing House in Solomons were in demand. “If you feel like you want to get down and walk about,” Bishop continued, “you can go down and walk about.” Working the Water, historian Paula Johnson’s 1988 classic on the fisheries of the Patuxent River, tells their story.

The ghosts of the mostly African American women seem to still be at the packing house, singing hymns to make the time pass. The floor men, both black and white, wheel in oysters and carry out shells. The manager marks with chalk on the black board, one tally for each gallon from a shucker who might shuck 10 to 15 gallons a day, their wages rising from 25 cents per gallon in 1924 to 50 cents in 1974. Fast shuckers could earn minimum wage. “A lot of people think themselves above shucking oysters … but I just love to make money,” Irma Gross concluded.

While the shuckers might be at the bottom of the social ladder, their job required intricate skill and knowledge of oysters. The packing house closed in 1978 because quality shuckers became hard to find and the oysters declined.

14430 Solomons Island Rd. Calvert Marine Museum conducts weekend tours beginning in May, with daily tours in June. 410-326-2042.

–Sandra Lee Anderson

Past Meets Future at CalvART Gallery

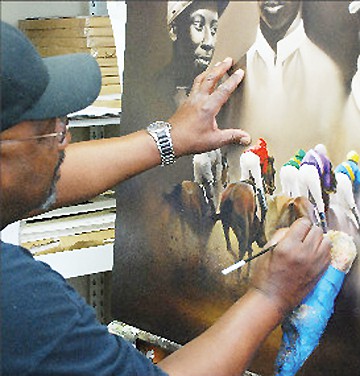

Four contemporary Black artists recapitulate the history of African-Americans from the era of tenant farmers to contemporary figures in cultural and political life at CalvArt Galley.

Tim Hinton of Upper Marlboro focuses on a variety of subjects: a classical cellist; three checkers players concentrating on their board; a man in Sunday suit, contemplating the Bible.

Hinton is joined this year by painter Arnold Hurley also of Southern Maryland, whose portraits of contemporary figures include President Obama and a stunning girl named Deandrea. CalvArt Gallery artists Ray and Phyllis Noble of Huntingtown also show colorful works of glass and fused glass.

The Calvert Arts Council assembled the show, which runs into March.

110 S. Solomons Island Rd., Prince Frederick, 410-535-9252, www.calvartgallery.org. W-Su 11am-5pm thru Feb.

–Elisavietta Ritchie