Walking Through Black History in Maryland’s Capital City

By Kathy Knotts

February’s designation as Black History Month began as a way to remember the important people and events in the history of the African diaspora, the communities found worldwide made up of native African descendants. In 2021, the observance may be more important than ever before after a year of reignited racial justice movements.

The streets of downtown Annapolis are currently lined with flags from 76 countries that represent African nations or places where significant populations of African descendants reside, including South America, the Caribbean and the United States.

“Driving up Main Street, it is an incredible sight,” said Mayor Gavin Buckley. “We were the landing site for ships of enslaved peoples. We’re known as the site where Kunte Kinte was sold into slavery. But in 2021, we showcase the pride of our African heritage by flying the flags of the African diaspora.”

The flag initiative was conceived by Adetola Ajayi, the city’s African American Community Services Specialist. The flags will fly throughout the month of February alongside a social media campaign highlighting the accomplishments of local African American women.

In Maryland, Black History Month events celebrate names like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, two African Americans who had a major impact not only here but across the world. But walk the streets of downtown Annapolis with a Watermark tour guide and you learn the names of other African Americans that were important to the capital city.

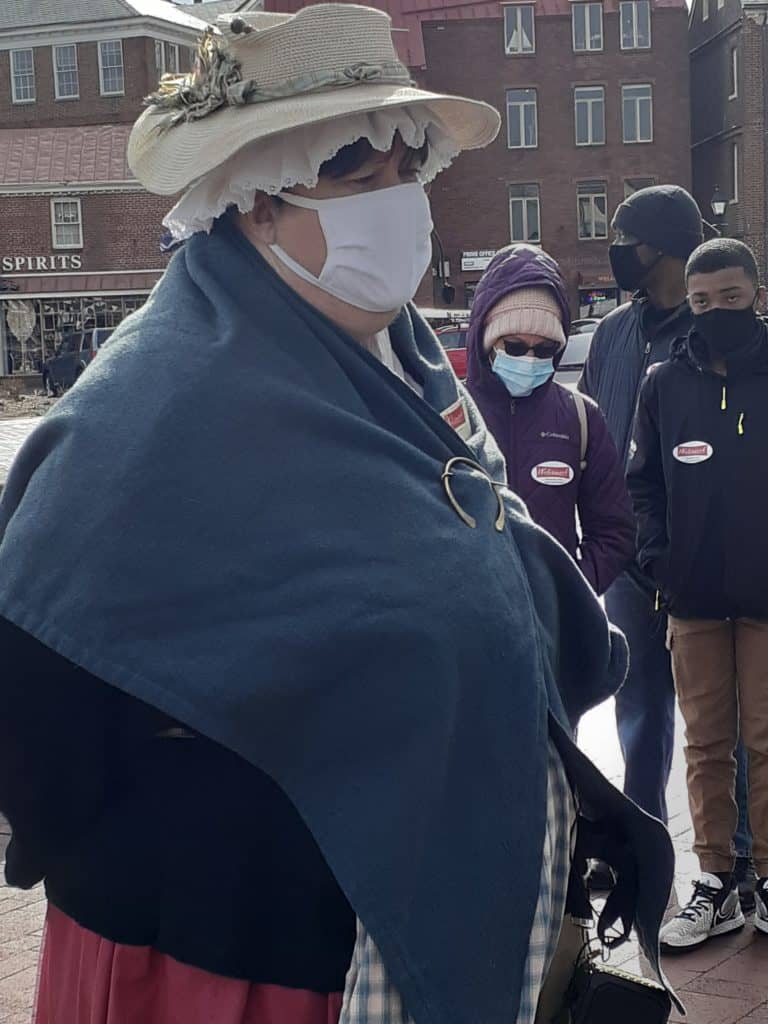

Every Saturday in February, Watermark offers its African American Heritage Tour, a two-hour stroll that begins at the Market House park, across from City Dock where slave ships disembarked over 300 years ago. The tour, developed in partnership with the Kunte Kinte-Alex Haley Foundation and named a “Heritage Award Winner” by the Four Rivers Foundation, starts with the Alex Haley statue, marking the significance of the author of Roots and the journey of his ancestor Kunte Kinte.

During colonial times, the labor of both enslaved and free blacks was the cornerstone upon which the tobacco economy was built. Guide Julie Brasch stops in front of the James Brice House, currently undergoing restoration work, to share the story of slaves who helped build it.

The tour takes you to the front steps of the William Paca House, also built with enslaved labor but later the site of the Carvel Hall hotel, where African American Marcellus Hall began work as a bellboy and retired as the superintendent of services.

The open hearth for cooking at the Paca House leads to a discussion of the significance of the foodways brought over from Africa, rationing portions of food to feed many mouths. Brasch also details how an enslaved person’s life in Annapolis was very different from those who lived on rural plantations.

In the 19th century, Maryland was home to more free African Americans than any other state. But that didn’t keep “slave catchers” from crossing state lines to find those who had escaped, or even forcing free Blacks into captivity.

Symbolically, the stroll continues uphill through local history, including the site of an early African American school at 91 East St., opened by the Order of the Galilean Fishermen, a Black fraternal society, in 1868.

Down the block, at the bottom of the hill that is home to the State House, Brasch shares the names of Michael Steele, Anthony Brown, and Boyd Rutherford—African American men who have served in government positions in Maryland.

Throughout the tour, she highlights the places and stories of the doctors, explorers, musicians, shopkeepers—people who contributed to the character of the region and who have been marginalized by history.

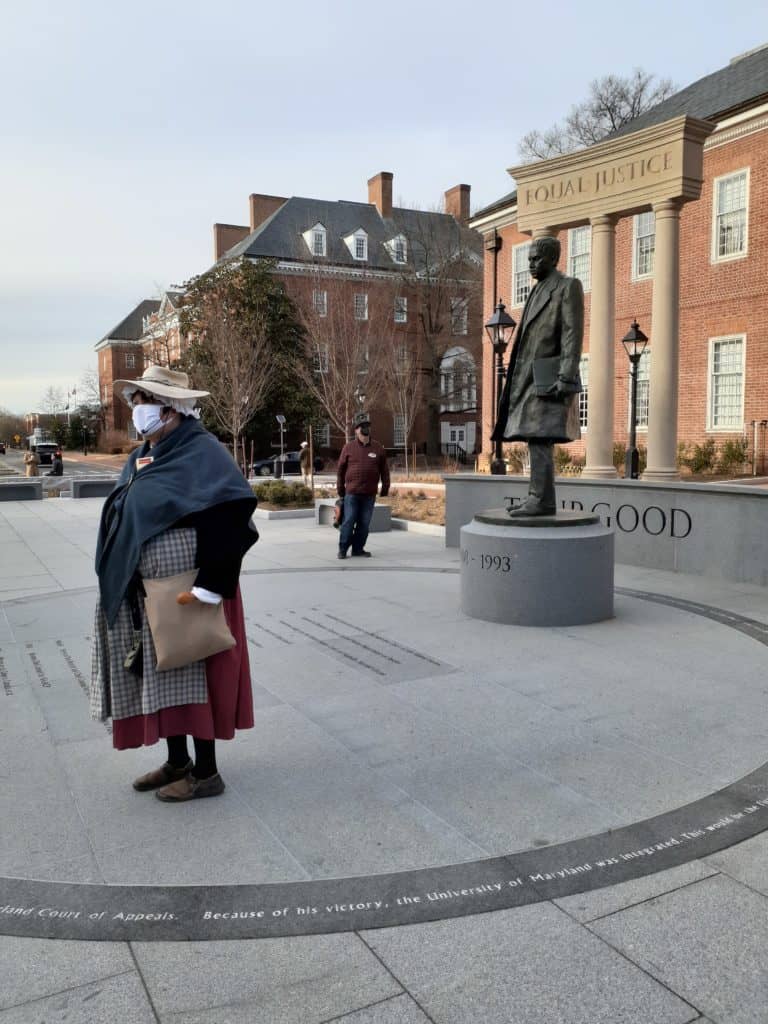

The tour culminates at the newly reopened Lawyers Mall, in front of the State House, at the site of a statue of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court Justice. But the story of the important contributions made by Black Marylanders is ongoing.

“I wish I could say that racism and prejudice were only distant memories,” said Marshall, while accepting the Liberty Medal in 1992. “We must dissent from the indifference. We must dissent from the apathy. We must dissent from the fear, the hatred and the mistrust…We must dissent because America can do better, because America has no choice but to do better.”

Tours are 1:30-3:30pm, $20 w/discounts, RSVP: www.watermarkjourney.com. The Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley Foundation receives 20 percent of the tour’s proceeds.