Wet, Wild or Mild?

A Winter Forecast for Chesapeake Country

By Kathy Knotts

In February, we turn to a portly groundhog to tell us when spring will arrive. In the winter, according to old wives’ tales and the Farmer’s Almanac, we should look at acorn gathering, stripes on caterpillars and the thickness of cornhusks or onion skins to tell us what winter has in store for us.

The 2022 Old Farmer’s Almanac says this winter “will be punctuated by positively bone-chilling, below-average temperatures across most of the United States.”

“This coming winter could well be one of the longest and coldest that we’ve seen in years,” says editor Janice Stillman. The Old Farmer’s Almanac uses solar science, climatology, and meteorology to predict weather trends.

When it comes to an accurate picture of what on the Chesapeake Bay will actually look like, we may be better served turning to experts with the National Weather Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association to tell us.

Will we see piles of snow and another bout with the polar vortex? Or will this season be mild with warmer days and less precipitation?

For meteorologists and climatologists, winter actually starts earlier than astronomical winter, which kicks off at the solstice, usually Dec. 21 and 22. Meteorological winter is typically categorized as the months of December, January and February. The same months when the weather in Maryland is as unpredictable as it gets.

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center published its Winter Outlook back in October stating that above-average temperatures are favored across most of the eastern U.S. this winter.

Chris Strong is the Warning Coordination Meteorologist for the Baltimore/Washington National Weather Service. “Our expectation for winter as a whole is that temperatures will be milder than usual. But that’s not to say we won’t see an Arctic outbreak from time to time. It will just be less frequent and not very long lasting.”

“Here in the mid-Atlantic we can get just about any weather threat, so we really have to be ready for anything.”

Chris Strong, National Weather Service

Strong says the weather service bases the winter outlook on a 30-year average of recorded temperatures; In the 2020s, “average” temperatures include data beginning in the 1990s. “Since we have shifted to the next set of averages, we aren’t looking at the data from the ‘80s. We have still had cold winters, but they have been less frequent. But still, looking back, we first started talking about polar vortex in the early 2010s.”

While NWS doesn’t make snow predictions in its winter outlook, Strong says we can also expect below average snow amounts due to La Nina conditions, which tend to produce more rain than snow for Chesapeake Country.

La Nina and El Nino are climate patterns born in the tropical Pacific Ocean that affect the weather patterns of the entire planet. The opposing forces alternate between bringing us warmer or cooler temperatures than average, based on how much heat and moisture is being pumped into the atmosphere. A La Nina year means warmer and wetter for Maryland.

Of course, a discussion of winter weather requires noting that winter looks quite different in 2021 than it did 50 years ago.

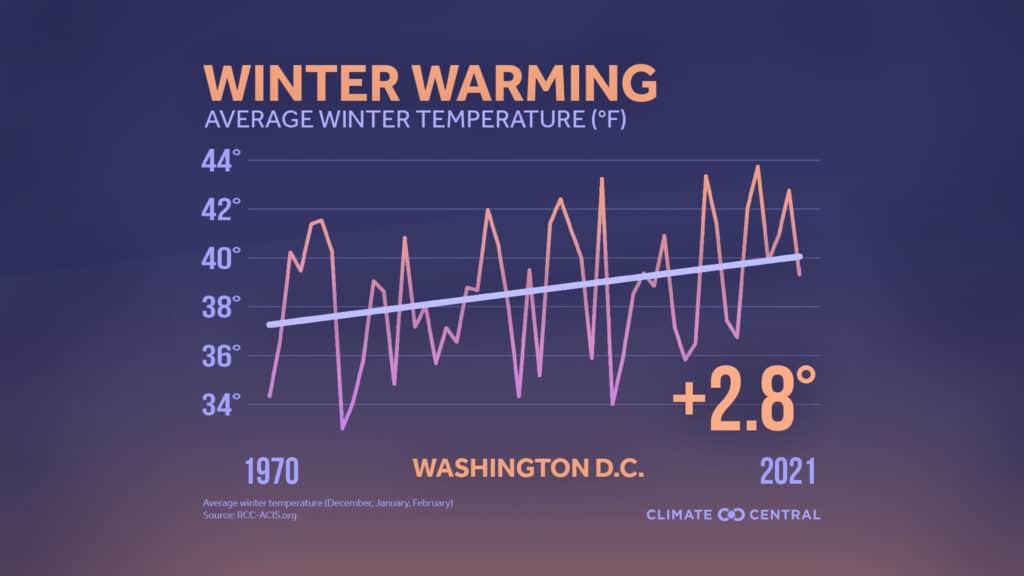

According to the nonprofit news organization Climate Central, winters across the United States just aren’t as cold as they used to be. Using 52 years of winter temperature data in 246 locations, their analysis shows an increase in average winter temperatures in 98 percent of locations.

Many of those locations warmed by two degrees or more. The places where winter is warming the most are the Great Lakes and the Northeast.

Climate Central’s research shows that winter is the fastest-warming season for most of the U.S. Over the past 50 years, average temps increased more in winter than in any other season for 38 states.

While some people in Maryland may embrace a warmer winter, Strong reminds us that being prepared never goes out of season. “Now through spring, when we do get those nice days that pop up time to time, we have to still be hyper-aware of the weather, and any warnings and the forecast,” he says. “When the wind comes up suddenly and you are out on or near the water, that water temperature can kill you. It remains one of our biggest threats.”

And while a warmer winter sounds nice it also has some negative impacts: More insects, less snow and ice for winter recreation, a declining snowpack out west that impacts water levels in reservoirs and crop irrigation, and lower fruit yields due to impacted tree development.

A warmer, wetter winter doesn’t mean that snowfall is a distant memory, though. “We may see a little bit of snow this week,” says Strong. “But it’s early season and it’s hard for it to stick. January and February are our snowiest two months. So anytime from mid-December through mid-March holds the possibility of snow.”

How much snow we get is still up in the air. “Anybody who’s from around here or been here a while, knows our snow is erratic. And it will be getting even more erratic with time,” says Strong. “We will have more winters with a single-digit snowfall, those will be more frequent. But at the same time we can still get those massive snowfalls. There will still be extreme weather events.”

Researchers at Climate Central note that there can still be cold winters under climate change. The likelihood of extreme cold conditions in a warming world is decreasing but it is not zero. Some locations will still experience extreme cold or cold records—just not as cold or for as long as in the past. Although a majority of the U.S. has experienced an increase in winter temperatures, some northern states, including the Dakotas and Montana, have had colder winter temperatures since 1970. Meaning Maryland can still experience deep freezes, similar to last February’s cold wave in Texas.

So what’s the biggest winter weather threat in the Chesapeake region? Is it snow? Ice? Freezing rain?

The winter threat we should worry about continues to be the element of surprise, says Strong. “Here in the mid-Atlantic we can get just about any weather threat, so we really have to be ready for anything.”

Nature’s Winter Predictors?

By Susan Nolan

Is a long, harsh winter on the way? Local experts look for signs in nature and say, “maybe.”

Deana Tice of En-Tice-Ment Farm and En-Tice-Ment Stables at Obligation Farm in Harwood says her horses are growing extra thick coats this year—so, we should prepare for a cold winter.

Esther Woodworth, a naturalist at Patuxent River Park in Upper Marlboro, advises us to sniff the air on a cold day. A metallic smell means snow is imminent. For a long range forecast, she keeps an eye on the sky and an ear on the pond. “The early migrations of ducks, geese and butterflies can mean winter is coming early. A lot of frogs making noise in August means they will be going underground early.” According to her, migrations happened right on time this year.

Park Ranger Dave Burman of Quiet Waters Park in Annapolis finds natural weather predictors all around him. “Woodpeckers sharing a tree indicates a cold winter is on its way.” And are the normally singular woodpeckers keeping each other company these days? “More so than usual.”

He also encourages us to look at the trees over the next couple of weeks. If the tulip poplar, red maple and red oak hold onto their leaves through mid-December, winter will be mild.

Lothian farmer Kayla Griffith of Griffith Family Farm grows kale and turnips. She reminds us that agriculture is a science and vegetables are products of their immediate environment, not the future. “The greens turn brown and die off sooner when it’s colder. With a mild winter, the growing season is longer.”

Naturalist Tania Gale at Battle Creek Cypress Swamp Sanctuary says natural weather predictors are fun, but “don’t put money on it.” “Some people say ladybugs gathering in crevices are a sign that we are in for a cold winter,” she says, “but the lady bugs do that every winter.”