|

||||||||||||

|

Volume 13, Issue 7 ~ February 17 - February 23, 2005

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Tons of clay fill local galleries by Carrie Steele Clay is the art of the elements. Ceramicists mine the earth itself and then knead, mold, sculpt and etch before immersing their earthen work in fire. For function or fancy, humans for thousands of years have been shaping clay — that will eventually be excavated by archeologists sifting through millennia of soil. The tradition continues as 878 modern artists — from Annapolis and Baltimore as well as 47 other states, Norway, Switzerland, Korea, Africa, Japan, Taiwan and Scotland — show how they’ve transformed earth into art in the largest clay exhibition in the country. It’s so big, it takes 122 venues and galleries to show off all the art. The Baltimore-based Tour de Clay brings thousands of sculptures, pots, wall art, statues and more to galleries from Baltimore through Virginia. Molding and shaping this expansive exhibit is Baltimore Clay Works, a non-profit ceramic art center that calls Tour de Clay the largest visual arts event in the country. “People can find everything from functional to decorative vessels and sculpture,” said Leigh Taylor Mickelson, Baltimore Clay Works exhibitions director. “There are also installtions as well: large-scale, multi-part sculptures that really create an environment.” Baltimore Clay Works coordinated shows throughout Baltimore, Annapolis and Washington, D.C. Tour de Clay even reaches out to Cecil County, where Stancill’s Clay Mine in Perryville displays clay pieces carved from its own clay in niches within the mine’s walls, and where a 2,200-pound pot resides on display. The driving force behind Tour de Clay is the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts Conference, which will bring more than 6,000 top clay artists, gallery directors and other clay-connected people to Baltimore in March. Baltimore Clay Works, the on-site liason for the conference, has been planning Tour de Clay since 2002. “The conference really spearheaded this project,” Mickelson said. “We took opportunity to the next level.” The Clay Works’ next job was to find guest homes for the visiting art. Clay Works looked at gallery space and presented appropriate exhibits to gallery directors, who then selected their exhibits.

But Tour de Clay is more than just exhibits: It’s a clay movement. Become a clay-convert through gallery openings; a Clay crawl, where various neighborhoods sell $10 coasters that get you meal discounts and other specials and an auction gala dinner. Art meets athletics in the Tour de Clay bike challenge, where a special map navigates you and your bike to various galleries. Just how big is clay art in Maryland next month? Gov. Robert Ehrlich declared March 3 Clay Day, when you can mold clay yourself and see demonstrations as artists visit schools to work with art students. Tour de Clay–Feb. 19-April 3; For schedules and happenings: 410-578-1919; www.tourdeclay.com.

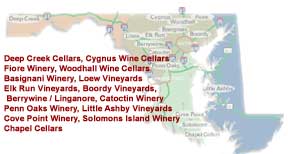

With vintage 2004, Southern Maryland turns wine country by Carol Swanson Making wine was Tim Lewis’ hobby when he worked at Patuxent River Naval Air Station. When Lewis was laid off in December 2003, he looked at his hobby in a new way. “I had friends and family who had said how much they liked my wines,” Lewis said just over a year later while walking the frozen fields of Cove Point Winery and Vineyard, where he has staked his future. Under Lewis’ care, grapes are now colonizing Maryland’s earliest settled lands, where tobacco ruled for centuries. Just a half-acre now, Cove Point Vineyard will grow to an acre this spring. This fall, he and his wife Sheryl will crush the first grapes grown in their own vineyards. Down Route 2-4 in Lusby, the nine-acre Solomons Island Winery sits on an inlet of the Patuxent River at the home of Ken and Ann Korando. In historic St. Mary’s City, the Korandos have opened a second winery, Chapel Cellars. “We thought we’d get more bang for our buck if we had more wineries in our region,” Korando said. “It’s also a nice place since it’s a tourist stop, too.” As well as making dreams come true for the Lewises and the Korandos, grapes could bring empty Southern Maryland tobacco fields back to life. Since tobacco farmers signed up for the state’s tobacco-buyout, agreeing to stop planting Maryland’s oldest crop, many of the fields have laid dormant. Grapes could bring not only a new crop but also a new economy to Maryland. Virginia shows that grapes can be not only a successful agricultural crop but also the basis for tourism. Two decades ago both Maryland and Virginia had 11 wineries each. Today, Virginia has grown to a booming industry with 94 wineries; Maryland has added only four, for a total of 16. Most are in Baltimore and Harford counties, but two — including the newest, Tilmon’s Island Winery, licensed this year in Queen Anne’s County — are on the Eastern Shore. Three are in Southern Maryland.  To prepare the ground, a 52-page report made to Gov. Robert Ehrlich this month details the path and the promise of what’s been a growth industry across the nation. Winery numbers have increased sixfold in the last 30 years, from about 600 in 34 states to over 3,000 in all 50 states today. To prepare the ground, a 52-page report made to Gov. Robert Ehrlich this month details the path and the promise of what’s been a growth industry across the nation. Winery numbers have increased sixfold in the last 30 years, from about 600 in 34 states to over 3,000 in all 50 states today. Recommendations in Maryland Wine: the Next Vintage range from mapping the state for vineyard suitability to rewriting laws to support the industry to marking highway routes to lead tourists to their destination to serving Maryland wine at state events. Already, the University of Maryland’s Extension Program has studied which vines are most conducive to Maryland’s climate, which is damp and cold for grapes. As further cultivation, Korando was awarded a two-year Maryland agricultural fellowship, a recognition that legitimizes grapes as a viable crop. The agriculturally rich Southern Maryland region shows great promise for vineyards, according to Maryland Grape Growers Association spokesman Tom Purvin. It’s a crop that can return riches. Purvin, for example, planted three acres of vines in his vineyard in 1999. Last year, he harvested seven tons of grapes per acre. Still, it’ll take some time for farmers to be convinced that turning their fields into vineyards can turn a profit. Grape vines take longer to take root and mature than tobacco, an annual planted and cut in one season. It takes several years for vineyards to produce grapes for wine making. With only 908 of Maryland’s 130,000 grape vines growing in Calvert (and 4,360 in St. Mary’s County), Lewis is an innovator. He began his backyard vineyard next to the fifth hole of Chesapeake Hills Golf Course by transplanting 12 vines from northern Maryland. Ten were merlot and two cabernet. Then he waited; not until the third year are new vines harvested. Last spring, Lewis saw plenty of fruiting buds but cut them so the vines would produce more the following year. “I hated to cut them before the fruit, but you need to think of the following year,” he said.

“Corn or soybean doesn’t make a fraction of that,” Lewis said. While he waits for his own harvest, Lewis is fermenting Cove Point wine from the juice of grapes grown in California, New York, Pennsylvania — with a few Maryland grapes thrown in for good measure. He’d like to use only Maryland grapes, but most vineyards already have their fruit contracted, he said. Only five of a dozen barrels now fermenting are made exclusively with Maryland grapes. Among them are cherry, strawberry and raspberry wines made from those crushed fruits. Lewis continues to experiment with different fruits and flavors, part of the wine making process he enjoys. Sweet fruit flavored wines are Cove Point’s specialty. Southern Maryland’s other two wineries followed a different route. “Common sense told me to see first if I could make a product that people would be interested in purchasing before I invested in growing grapes,” said vintner Ken Korando, whose background is in investment banking. He began a winery before he planted a vineyard. Like Lewis, the Korandos’ new career grew from a hobby. The couple enjoyed hosting gourmet dinners with homemade wines. “We had friends asking where they could buy our wines,” he said. Researching the business led him to the University of California at Davis, which is renowned for its classes in the industry. This spring, he’ll be telecommuting. Solomons Island Winery and Chapel Cellars Winery were licensed to make wine last summer. “It’s a process of making, tasting, pouring it out and making it again,” said Korando. The sister wineries sold nearly 600 cases in the last three months of their first year, 2004. In September, the fledgling wineries got a boost at the Maryland Wine Festival, when Solomons Island’s wines won Governor’s Cup awards in its first competition. Their white merlot took a silver medal and their sauvignon blanc won Best of Class in the dry white category. Both wines now sell in 47 retail establishments. With the taste of success on his palate, Korando is now thinking vineyards. He’ll plant six acres this spring on land leased from Historic St. Mary’s City. He has leased 40 more acres for later plantings. “I would rather grow grapes than houses,” said Korando of the future. Find Southern Maryland’s wineries at www.covepointwinery.com and www.solomonsislandwinery.com.

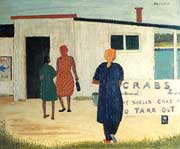

Calvert Marine Museum seeks your stories by M.L. Faunce Gone are the days when seafood houses were among the largest employers along Chesapeake Bay. Now they’re museum pieces. Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michael’s plans to replicate an entire former Crisfield packing house, contents and all. In Solomons, Calvert Marine Museum already preserves the Lore Oyster House as an exhibit hall. Now, with your help, the Calvert County museum seeks to further document the “long and colorful history” of oyster packing and crab picking industries in Southern Maryland. “Larger businesses are better documented,” says museum curator Richard Dodds. “It’s the smaller operations that are proving more elusive.” Museum staff have been combing records and collecting information and photographs on seafood processors in Calvert, St. Mary’s and Charles counties, with help from the community and descendants of former packing house owners. But more information is needed to capture the worth and flavor of the times for an upcoming exhibit that will also include interviews with the men and women who were long-time oyster shuckers and crab pickers back when roads were paved with oyster shells. In Calvert County, the museum seeks information on Tommie’s Crab House of St. Leonard and Sollers and Dowell on Sollers Wharf Road. In Charles County, sought are information and photographs on Hill and Lloyd of Rock Point; Patuxent Seafood Co. owned by Linwood and Allan Sollers; and Henry Messick, both junior and senior, of Benedict. St. Mary’s County had the largest number of seafood houses over the years, and the museum’s wish list is just as big. They’d like to hear from you on: Edward T. Oliver of River Springs; Wm. W. Mattingley of Mechanicsville; James Hall of Cornfield Harbor; Frank Alvey, Joseph M. Hazel and B.G. Pogue of Compton; J.J. Morris Co., of Hollywood; the Norris Bros. of Yankee Point; Charles Connelly of Leonardtown; William P. Powell and Hugh F. Smith of Airdale; C. Robb Lewis and the Miller Oyster Co. of Wynne; and R. Biscoe Bros., L.G. Railey, Stone Seafood, Bernard Clarke and Fred V., G.L., & W.W. Dunbar, all of Ridge. It’s a tall order, and it may take going back in your memory or digging through old photo albums. But with fewer oysters on our plate or crabs on our table, museums may soon be the only place we learn about the thriving industry that is part of our Maryland heritage. In Calvert and Charles counties, contact Richard Dodds: 410-326-2042 x 31. In St. Mary’s, contact Robert Hurry: 410-326-2042 x 35. Or write the museum at P.O. Box 97, Solomons, MD 20688. On the Eastern Shore, another seafood plant has closed, continuing a sad trend in recent years. Fifty-five workers in Pocomoke City were laid off last week with no notice when Mid-Atlantic Seafood sold out to Sea Watch International, which said it will move operations. The 27-year-old plant supplied clams to restaurants across the country … |

|||||||||||

In Virginia, the menhaden panel of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission acted wisely last week when it decided to cap the harvest of menhaden in Chesapeake Bay at present levels through 2007. Tiny menhaden, a primary food for fish, are harvested in huge quantities — 110,400 metric tons last year — for their oil. Fishing pros blame overharvesting for a recent trend of emaciated rockfish …

In Virginia, the menhaden panel of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission acted wisely last week when it decided to cap the harvest of menhaden in Chesapeake Bay at present levels through 2007. Tiny menhaden, a primary food for fish, are harvested in huge quantities — 110,400 metric tons last year — for their oil. Fishing pros blame overharvesting for a recent trend of emaciated rockfish …