|

|||||||

Going with theFlow

|

|

|

photo by Carrie Steele Bobby Haley and Doug Willis point out the single dumpster now used to collect all household recyclables — glass, plastic, metal and paper — at Sudley Convenience Center. |

Anne Arundel is among the first counties in Maryland to send a messy conglomerate of newspapers, plastics and everything else melt-able or pulp-able to a new Waste Management Recycle America plant just over the county border in Elkridge. There, technology takes over sorting we used to do by hand.

In that churning, writhing recycling warehouse of conveyor belts, gears and giant machines, our Tide bottles and last week’s Bay Weeklys are separated, reunited with like materials and dispatched round the world to some four dozen mills that promise to reuse Anne Arundel County’s waste.

Single-stream is the wave of the future. Once we get past our confusion, it’s supposed to make recycling even easier, helping us waste less and save more.

Wasting Less

That’s a goal much desired by state and county recycling planners, who’ve established a county goal of 50 percent of the waste stream.

In 2005, Anne Arundel County citizens recycled roughly 112,200 tons, or 31 percent of their waste. County-wide recycling broke down into 52,600 tons of yard waste and 59,600 tons of paper, cans, bottles and jars.

“We’ve been hovering at 31 or 30 percent for about four years,” said Jim Pittman, deputy director for waste management services in Anne Arundel County. “We know that people are putting recyclables in the trash can.”

Anne Arundel citizens rate just a sliver higher than the national recycling rate average, 30.6 percent, measured last in 2003.

Locally and nationally, that’s not great news.

“If you’re a recycler,” said Pittman, “you feel good about it. If you’re an outsider looking at it, a third is not a lot of volume. That means two-thirds of it is filling up our landfill.”

Adding commercial recycling as well as residential, as the Maryland Recycling Act requires, raised Anne Arundel’s rate to 40 percent in 2004, the last year it was compiled.

Single-stream recycling will, planners expect, improve our recycling score.

“Generally, single-stream results in higher participation rates because it’s easy, so you’re capturing more material,” said Pat Franklin of the Container Recycling Institute, an affiliate of the Worldwatch Institute, headquartered in Washington, D.C.

Paying Off

With more recycling, Anne Arundel County hopes for a bigger pay-off.

Recycling is a costly county business: some $10 million per year, including the collection of yard waste and recyclables, plus outreach and recycling containers.

County income from recyclables doesn’t come close to paying the bill. Anne Arundel earned about $1.5 million on recycled materials last year. The county’s cut from all the materials that go through the single-stream processing machine could raise profits closer to $2 million this year.

Another savings comes from diverting trash from landfills.

“Every time we open a new landfill it’s a multi-million dollar investment,” Pittman said. “You have to find a site, acquire the land and build it. There’s no other place we could put a landfill at this point.”

Even so, recycling will never pay for itself. Fuel prices, county recycling program manager Tracie Reynolds said, will always cause collection costs to outweigh profits. It’s been that way since the beginning.

Flowing Easier

The waters of single-stream recycling began churning in the desert. Phoenix, Arizona was the first municipality to test-drive the process with a custom-made machine. Since 1991, recycling plants from California to Virginia have made the switch.

Anne Arundel County jumped on the bandwagon on June 1 after 14 years of instructing us to sort our recyclables, washing out cans and bottles and keeping paper separate from plastics.

Now, we’re unlearning it all.

No wonder good citizens who toss their recycling into Sudley’s single bin worry that their effort would go directly to the landfill. No wonder Haley of the Sudley Center and recycling program manager Reynolds have been doing lots of hand-holding.

“We’ve been watching this technology. Now they’re up to fourth generation technology, and we knew we wanted to do this,” Reynolds said. “It was just a matter of when, and now’s the time.”

Anne Arundel County chooses a recycling contractor based on services and price; the county purchasing department settled on Waste Management Recycle America, said Reynolds.

When Waste Management Recycle America announced it was building a new plant with the technology to move all the material in one stream, “of course we went with it,” Reynolds said. “It’s easy.”

Elkridge, in Howard County, was chosen for its proximity to major highways and byways, making access easy for incoming trucks.

At home, with one stream, just one truck comes to pick up recycling at your curb.

“Most people should see one less truck in their neighborhood,” Reynolds said. “Or because [the recycling collector] can use two trucks to pick up at the same time, people get it picked up faster.

At recycling centers, citizens just make one stop, and that makes the center — with criss-crossing cars, people and assorted loads of recycling, trash, branches, tires, rubble and old appliances — much safer.

Single-stream is easier for Haley and his associate, too.

“It saves us from hauling stuff,” says Sudley staffer Doug Willis of the new single-stream system.

Setting the BarUnder the 1988 Maryland Recycling Act, each of Maryland’s 24 jurisdictions — 23 If a jurisdiction can’t meet its recycling percentage, the state can refuse to issue building permits for new construction. “Every county in the state has to report to the Department of the Environment what their recycling rate is,” said Tracie Reynolds, Anne Arundel Recycling program manager. Counties track residential rates, but the commercial rate comes by questionnaire from individual companies. Large companies have their recycling picked up by a private hauler, which usually takes it out of the county. In Anne Arundel County, commercial recycling makes up 65 percent of the total tonnage. Both Anne Arundel and Calvert counties have set higher goals. Calvert, which recycles in a dual-stream now but may see single-stream recycling within a year, has a recycling rate of 40 percent. “Forty percent is our goal, so we reached our goal. Woo-hoo!” said Shirley Steffy, Calvert County’s recycling coordinator, who says they selected their Recycle America processor in Capitol Heights based on price and proximity to Calvert. “Our rate sounds really good, said Anne Arundel’s Reynolds. “But it’s misleading because residents are only doing 30 percent of the county rate. A lot is being lost in residential.” |

Recycling Easier

Citizen recyclers get it easier, too, now that Anne Arundel County has taken the high-tech path of least resistance.

Not only don’t you have to sort, wash or separate. Recycle America will also take any plastic numbered one through seven (look on the bottom), plus all the glass bottles, paper and metal cans you come up with in daily life.

“If there’s a product and you’re not sure [it’s recyclable], I encourage you to put it in,” said Reynolds. “There’s always new markets developing. Our processor is recycling margarine tubs now, and yogurt containers, too. The only way they see it is if they see it. If we don’t put it in the bin, they don’t see it.”

“We’re trying to make it easy,” added Pittman. “Don’t worry about the yogurt on the bottom, whether it’s dirty, narrow neck: It’s all irrelevant. That’s an old rule.”

Recycle with abandon, but keep the plastic bags out. At the Elkridge center, rubber gear-like stars that separate paper from glass and plastic slow down when derelict plastic bags wrap around their axles.

Movin’ & Shakin’

|

|

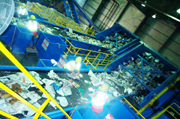

photo by Carrie Steele Workers at Waste Management Recycle America monitor conveyor belts carrying recycling; quick hands pull off non-recyclables like plastic bags. |

The new single-stream plant sees some 14,000 tons of recycling each month, 800 tons per week coming in from Anne Arundel and Howard counties in Maryland, plus Washington, D.C., and Fairfax County in Virginia.

Anne Arundel County contributes some 3,000 of those monthly tons.

When site manager David Taylor flips the switch to the new recycling sorting machines, they rumble like a Category 3 hurricane blowing through. Conveyor belts sweep past you, below you and above you like a futuristic superhighway, carrying streams of drink bottles, yesterday’s newspapers, cardboard boxes, scraps, Coca-Cola cans and everything else that’s been binned on a street curb or recycling center.

Strange things — from car parts to cables, garden hoses, ropes and once a whole dead pig — pass by along with true recyclables.

Whatever, it’s all sorted and organized by this monstrous $8-million-dollar, Dutch–made machine that does all the sorting work we gave up on June 1.

“It’s basically a big computer program that runs everything,” said Taylor.

Trucks dump their loads in huge warehouses where recycling mountains rise over 20 feet high. Dozers push it around like fill dirt and onto the first conveyor belt. The load whizzes past a pair of heavily gloved workers who move like a fast-forward movie to rip plastic bags and any other vagabond trash off the line. The stream then flows uphill over those spinning rubber gears, optical sensors and infrared lights, with bottles filtering down and paper and cardboard carried up, like salmon swimming upstream. Fifteen feet below, another uphill stream-sorter is at work.

Plastic is the target of several stations, the last an infrared light that fires a fast puff of air to blow plastics up into a separate chute while trash falls into a bin below. Huge magnets cause cans to jump off the belt.

Tending the new machine are some 82 quality control workers, up from the 18 at the old facility. In addition, 10 mechanics keep the mammoth machine up to its job.

|

|

photos by Carrie Steele Recyclables are sorted and separated by machines using thousands of rubber gear-like stars like the one held by David Taylor, site manager at the Elkridge plant of Waste Management Recycle America. |

Quantity and Quality

How well does the big shaker do its job? Depends on who’s the evaluator.

Taylor says his Elkridge site has the best sorting technology in the country.

By one measure, the Maryland machine sort through 66 to 70 tons per hour. A cousin machine in Minnesota can sort only 35 to 40 tons.

Another measure, according to the Container Recycling Institute’s Franklin, is the precision of the sorting.

“The bad news,” said Franklin, “is that by mixing everything together — glass, plastic, aluminum, paper — you have much higher rates of contamination.”

Specifically, skeptics like Franklin look at paper sent to mills.

Paper slated for recycling has the largest contamination problem, said Franklin, because shards of glass and plastic can foul paper-recycling machines.

“When it gets to mill, it costs them a lot of money. The paper mill machinery is made for paper; now they’re getting paper, glass, plastic,” Franklin said.

Taylor begs to differ.

You’d be “hard pressed to get glass in paper” with their new machine, he said. “Those 100,000 stars do most of the separation. We don’t have any glass in our paper.”

Looking Downstream

Downstream, materials scatter into the bustling market of recycling. Waste Management sells to its buyers based on price, says Taylor. And better quality fetches a better price.

From the Elkridge center, material goes to over 50 different mills. Ninety percent of our material goes overseas, Taylor said.

The bulk of the recycled stream is paper and cardboard — the fiber — which heads east to China, where it’s blended into a soupy pulp and reincarnated into new rolls of paper.

Much of the ground glass goes to Coca-Cola. That mixture of glass — sorted by color by optical sensors — has to be 99.9 percent pure, Taylor said. Two grades of glass are sorted by color and crushed.

Steel goes to Bethlehem Steel.

Plastic goes to plastic mills owned by Waste Management.

Aluminum, the big money-maker, goes to Anheiser Busch for some $2,000 per cube.

About six percent of the load is trash, residue like plastic bags and food that have to be landfilled.

Closing the Loop

Throwing a drink can into the recycling bin gets it away from you. But that’s only the first step in taking responsibility for the mess we make. Cleaning up after ourselves means seeing our waste through to the other side — not just getting it out of sight out of mind.

Anne Arundel County says it isn’t in the business of seeing through to the other side. “We don’t have enough people to track it,” Reynolds said.

So the county puts its trust — our trust — in the company hired to do the job: Waste Management Recycle America.

County recycling is, waste management deputy director Pittman says, “really a part of private sector” after it gets to the plant.

“I could audit their books at any time,” added recycling program manager Reynolds. “This is a huge contract with very specific performance parameters that they abide by. I know where our paper goes. I know where the majority of our tonnage goes by the processor — who reports back to us — and we feel comfortable with that.”

In closing the loop, the county buys recycled paper from the contracted supplier, Office Depot. But only when recycled paper costs the same or less than non-recycled.

counties plus Baltimore City — had to develop recycling programs. Jurisdictions with populations over 150,000 had to recycle 20 percent of their waste; populations less than 150,000 had to recycle at least 15 percent.

counties plus Baltimore City — had to develop recycling programs. Jurisdictions with populations over 150,000 had to recycle 20 percent of their waste; populations less than 150,000 had to recycle at least 15 percent.