|

||

Critical of Maryland’s Critical Area Law?Anne Arundel citizens get two votes to untangle a knotted ball of stringby Alexandra Brozena

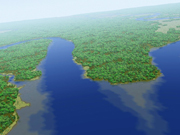

Depending on what side you’re on, Maryland’s Critical Area law is either the Chesapeake Bay’s champion or a homeowner’s nemesis. Now Anne Arundel voters get the chance to elect candidates who will defend their position on the 22-year-old law protecting the waterfront and 1,000 feet inland. To strike a perfect balance between waterfront delight and environmental damage, the state mandates that the law be revised every six years. Anne Arundel County lawmakers started the job but have postponed approving this year’s revision until after November elections. So you’ve got two chances — the September 12 primary and the November 7 general election — to vote your mind on Critical Area. (Calvert County is in the final phases of revising its Critical Area law.) Four Anne Arundel County Council members — all Republicans — are running for re-election. Two have no opponents: Ed Middlebrooks of District 2 (Glen Burnie) and Ronald Dillon Jr. of District 3 (Lake Shore). Cathleen M. Vitale of District 5 (Severna Park) has one general election challenger, a Democrat. Edward R. Reilly of District 7 (Southern Anne Arundel County) has two general election challengers, a Democrat and a Green. Once the council is done with the bill, the county executive can either accept the legislation or veto it. You get a vote on that decision-maker, too, as five Republicans and two Democrats are running in the primary to take over from Janet Owens, who is stepping down after eight years under the county’s two-term limit. Opening a Legislative WindowThe postponement might be procrastination or opportunity to fix holes that make the law evasive and difficult to enforce. “We were ready to tackle it as a council,” Reilly told Bay Weekly. “We anticipate a significant amount of citizen input and a significant amount of amendments.” But, he explained in reference to the upcoming election, the council had “a limited legislative window.” “I think the fear is to have all of this input, all of these adjustments, and then have to go through the entire process [again] with new faces on the council,” Reilly said. Councilman Dillon agreed that revising the law to make it simple and fair is worthwhile no matter how long it takes. “I think many violations occur because homeowners have no idea they are in Critical Area,” Dillon said. “The easier it is for a layperson to understand, the better chance the laws will be adhered to.” Dissecting the LawIn June and July, County lawmakers introduced to citizens their best thinking so far on how to revise the law. Three public meetings were held in the south, central and north parts of the county. During the final public hearing on July 11, passions were high and opinions trenchant as homeowners nit-picked the law late into the night. “I’m not offended by the law,” said Arthur Held of Crownsville. “I’m offended by the thought that you can’t pull up the roots of poison ivy.” Anne Arundel County seemed to be juggling, as County Attorney Linda Schuett summarized the revisions as a “zero tolerance policy, a policy that prohibits clearing unless we know what you’re doing beforehand.” At the same time, Schuett said, this year’s revisions take into account the complaints of waterfront homeowners, “allowing routine gardening.” “Clearing will still be prohibited without prior approval,” she said, “but routine gardening and landscaping of existing gardens will be allowed.” In other words, she explained, a homeowner within the Critical Area can transplant an azalea and cut the lawn without County consent or interference. Riverkeepers and environmentalists, however, argued against relaxing the law. What is routine gardening? they asked, and how long until land clearance on the waterfront becomes “routine”? Bob Gallagher, the West and Rhode riverkeeper, said “This administration has a concern with the doctrine of property rights that I think stretches the doctrine beyond the limits, and that is in conflict with the objective of protecting the Bay.” Gallagher, along with fellow riverkeeper Drew Koslow of the South River, criticized the revised Critical Area Act for failing to raise fines, for increasing maximum land clearance without a variance to 30 percent, and for inadequate enforcement. Schuett disagreed with the riverkeepers’ accusations. “You could argue that some of [the revisions] take a homeowner’s perspective, but for the most part the intention of the bill was to tighten and strengthen the Critical Area provisions. “You always have to locate development to avoid disturbance to trees,” she said. Homeowners still couldn’t be satisfied. As Schuett and her colleagues tried to clarify Critical Area, the legal lingo continued to perplex residents. To these homeowners, the Critical Area Act is like a knotted ball of string. The more lawmakers attempt to undo the knot, the worse the mess gets. Some waterfront residents, however, argue that the pleasure of living on the Bay demands sacrifice if the water they treasure is to be protected. “I would like to ask the Critical Area Commission to stop giving variances,” said Barbara Miller of Fairhaven, reasoning that exceptions to the law lead to McMansions nearly at the water’s edge. “It affects the whole Bay.” Your Window“From that meeting,” said Councilman Reilly, “there appeared to be a significant number of well informed citizens who pointed out significant flaws to the law that was proposed.” The postponement provides time for these problems to be revised. It also gives Anne Arundel citizens time to take part in democracy as they vote their opinion of the law. Alexandra Brozena, of Davidsonville, studies English and environmental science at Tulane University. This is her first story for Bay Weekly. |

||

|

|

||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. |