|

||

|

||

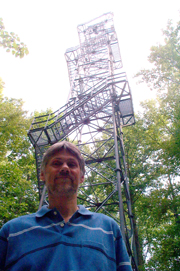

Minutes to BurnLocal scientist keeps UV rays at Bayby Carrie Steele, Bay Weekly staff writerScientist Patrick Neale climbs a 120-foot metal tower every day. That’s 168 steps of metal grating and two skinny handrails zig-zagging up above the tree canopy. Sometimes, if he forgets something at the bottom, he has to climb it twice.

What lures him to the pinnacle of the tower is a shoebox-sized white box equipped with a tiny air conditioner. The top of that gargantuan tower at Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater — from which you can see the Bay Bridge, the Eastern Shore and the Naval Academy radio towers on a clear day — is the best place to catch ultraviolet light. Neale is not looking for a sunburn. His job is studying and documenting ultraviolet light that falls on Chesapeake Country. That’s the same UV — the shortest wavelengths of light — that cause us to turn lobster red in the summer if we go sans sunscreen. “There’s not as much of a common awareness as there should be,” says Neale, who’s been studying the effects of UV for 15 years, 13 at the Smithsonian. Neale knows UV. He’s traveled to Antarctica to study UV light there. One of 17 senior scientists at Smithsonian, he works daily to understand our environment. Now you can use Smithsonian science to stay healthy. On the Smithsonian website, watch as a chart tracks UV light minute by minute each day. Color-coded marks indicate how bad the UV light is: the UV index. Look to the right and that index number reveals a range of how many minutes before you’ll start showing signs of burn if you venture out bare-skinned. Television weatherpeople use a forecaster to tell you the UV index, but on the Smithsonian site you can get actual numbers. Most summer mornings, the UV index is zero to three — green — meaning you’d have to get 35 to 100 minutes of unprotected, uninterrupted sunlight to burn. Throughout the day, that risk increases to an index of six to eight, meaning you’d get pink within 11 to 40 minutes. Along Chesapeake Bay, we have it easy. The index rarely breaks 10. “If you’re up in the Himalayas, the index can be as high as 20,” Neale says. “People that live there are completely dark and wear these wide-brimmed hats.” It’s true you can get burned on a slightly cloudy day, Neale says. Heavy clouds block out some UV, but when the sky’s bright white, UV can still come down strong. His instrument — the SR-18 — measures light coming from all directions, not just directly from the sun. That’s because our skin receives light from all directions, sometimes even below, and in all temperatures. Neale recounts the story of some unfortunate voyagers in Antarcica who forgot their sunscreen and burned — even though the air temperature was zero degrees — because an ozone hole formed over the continent, letting through a sky-high index. Ultraviolet B and A are light waves so short that we can’t see them, with UV B even shorter than UV A. The shorter the wavelength, the more power it packs. Luckily, we get less of those shorter wavelengths and more of the longer ones. It’s the medium-length wavelengths that are the most dangerous, for they’re short enough to be harmful and more plentiful. “UV B is most important in terms of health effects; UV A is more important in terms of ecosystems,” Neale says. The Smithsonian set-up isn’t a health lab. Neale says his focus is on UV effects on marine food webs and photosynthesis, but the information is broadly useful. The National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg is interested in Neale’s work to help understand what damage UV does to paint on cars and buildings. Before Neal’s tower rose in the mid-1990s, the UV monitoring setup used to sit atop silos. “They were the tallest objects at the time,” Neale says. Trees grew up and began to block light from the sensors. Now, nothing blots out the sky over the weather and light instruments. It’s so tall, Neale says, that the only branches he has to clear from the platform are dropped by high-flying, nest-building osprey. Check out today’s ultraviolet map at www.serc.si.edu/labs/photobiology/monitoring_liveUV_data.jsp. |

||

|

|

||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. |