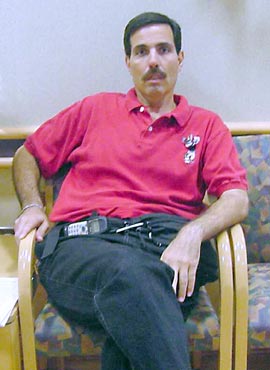

Another man’s heart gives Chesapeake Country teacher Steve Ferralli a new lease on life.

Another man’s heart gives Chesapeake Country teacher Steve Ferralli a new lease on life.

Story & Photos by Kathleen Murphy

As the gurney transports Steve Ferralli from 4NW into the operating room, he fights back tears and raises his arms in victory. On this evening of September 7, family and friends have, with Steve, placed their trust in the dedication and skill of the transplant team soon to stitch a new heart into his chest. Their prayer is that Steve’s fearful journey of these last seven months is about to become the passage to the perfect heart, linking the tragedy of one family to the rebirth of another.

Redefining Normal

On July 19, Steve and his family had come home from Washington Hospital Center to a new standard of normal: A mechanical heart pumped the blood that kept him alive. The new normalcy was a vigil of charged batteries, cleanliness, good health. Family life was filled with new fears and worries.

Those months were also a time of learning anew, little by little, how to enjoy the time given, appreciating the miracles that kept Steve alive.

Steve prepared for his fall return to Southern Middle School to teach seventh grade industrial arts. He was looking forward to a new curriculum that would have him teaching computer basics to his students.

Sharon, his wife, was excitedly preparing for her second year as principal at Lake Shore Elementary School in Pasadena. Their children, Philip and Bethany, were anticipating the upcoming soccer season at Northern High School of Calvert County. This sports family was geared for another great season. Sharon’s e-mail link to family and friends slowed from daily to weekly.

July 21: Last night was a good evening and today was purely a family day. The first one in months and months … It was nice being together in a normal situation.

By September 7, Steve had been back to work at Southern Middle School a few weeks. The days were going well, though minor problems with the cumbersome pump kept the Ferrallis primed for response.

“The first weeks home held just a few scares — and a real emergency,” Steve said. “Every time the power went off (due to thunderstorms) my alarms would go off and scare us out of our chairs. I was on battery power every time, so we didn’t need any heroics. I also managed to make the clips on my batteries fall apart one night. Fortunately I could put it back together with a knife on the table.”

Steve was remarkably well, feeling upbeat about how the days were unfolding. The details of teaching a group of active seventh graders while wearing a mechanical heart pump were falling into place. He had been assigned an assistant to help in the classroom. He was surrounded by a supportive staff, and steps were in place for emergencies.

When the phone rang in his office at 8:40am, the call that Steve knew would “scare” him had come. Friend and co-teacher Barry Clark heard Steve banter — as he did whenever the phone rang — that it was probably the hospital calling with a transplant. This time, it was the real thing. Sandy Couples, the heart transplant coordinator at Washington Hospital Center, said there was a strong possibility that they had a heart for him.

August 22: On Thursday, I learned that Steve was a high priority transplant candidate. From here on out he will be called to WHC for every O+ heart. Even if it is designated for a 1-A patient, Steve will be the back-up recipient. There could be several false alarms. I’m told they will wait for just the right heart for him because he is sooo active!

Sandy Couples’ words did not register at first. As in a trance, Steve pushed his chair backwards across the room, absorbing their meaning. This was it. He hoped it was not a false alarm.

Moments later, at Lake Shore Elementary School, Sharon picked up her phone to hear Couples say “I think we have a heart for you.” She thought, this is his heart. She knew she was ready.

This is the day that transplant recipients and loved ones plan in their minds. It is the day that will alter their lives forever. Yet no amount of planning could have anticipated the mental preparation Steve and Sharon would now make. Still, both were ready. There were no second thoughts, no turning back.

Sharon made the long drive from Pasadena as Steve journeyed from Lothian with co-workers Barry Clark and Loretta McFadden. Along the way, Steve, sitting in the rear seat, phoned family and friends.

Heart Failure

Steve Ferralli takes a deep breath and shakes his head as he reviews the days last winter when this unbooked passage began. The shortness of breath on stairs was not a huge concern. He was in good health, in good shape. He thought about the inevitability of aging, yet he had no clue that his own heart had begun to fail. In weeks, he would learn that without a new heart he would die.

No one knows exactly when Steve’s heart began to fail. A virus days, months, years before might have caused his heart to deteriorate. No one realized initially that his breathing troubles were an indicator of his heart’s abnormal growth.

An enlarged heart loses muscle tone as it struggles to adjust to changing responses from within. A strong, muscular heart beats rhythmically as it provides life to the body, pumping nutrient and oxygen-rich blood to wash through the organs, arteries and veins.

It delivers blood to 300 trillion cells. Each beat provides a push, then a pull, of life-sustaining blood in a finely tuned pattern of expansion and contraction as valves open and close. Oxygen poor-blood is pumped into the right chamber to be enriched with oxygen in the lungs. As oxygenated blood returns to the heart, it is propelled out as valves on the left side contract. The heart rests as it fills with blood. Then the quick sequence begins again.

A normal heart pumps 1.3 gallons of blood per minute. In a day, nearly 2,000 gallons of blood courses through the body. A normal pattern of pumping is defined in a range from 20 to 30. Steve Ferralli’s range dropped to five.

His organs reacted in terror. The heart is able to withstand some degree of inefficiency; other organs, such as the kidneys, fail first. Shortness of breath is one way the body sends an alert of this failure. Though Steve had no chest pain indicating heart damage, his body was beginning its perilous descent.

By early February, Steve’s heart rate was a high 190. A normal resting heart rate ranges from 60 to 100. Steve’s rate was so high because his heart was working so much harder. His heart was working faster, yet pumping less. Damage to the left chamber was creating an electrical storm.

The journey to a new heart began in earnest on a blustery day in March with the decision to airlift Steve to Washington Hospital Center. Recognizing there was nothing more that he could do, Dr. K. Yazdani at Calvert Memorial Hospital saved Steve’s life.

Thus began a tenuous journey of surgeries and recuperation. Two mechanical pumps — known as Ventricular Assist Devices and called VADs — were inserted into his chest to keep both chambers of his heart operating efficiently. By April 10, he passed through a second surgery to remove the right-VAD. But the damage to the left chamber could not be controlled except by the assist device.

As the search for a new heart began, the left-VAD, called LVAD, kept Steve alive. He would not learn of this critical need for weeks, for he drifted in and out of consciousness. His family knew.

The Big Wait

September 9: With that news a whole preplanned chain of events was put into place. By 10:30am, we had reported to WHC for the “big wait.” There were lots of tests to be completed on Steve and the donor.

At the Washington Hospital Center, an eager transplant team awaits the Ferrallis. They are smiling and so upbeat that, Sharon says, we were “like Christmas to the team.”

The first of many tests begins. There is blood work and X-rays. Immunosuppresants will help Steve’s body accept, even as it tries to reject, the transplanted heart, just one of the unknowns ahead: How will Steve’s body react to this new heart?

Steve and Sharon recognize familiar faces, for this team guided them through the grueling days from March into July. This transplant team shares everything, good and bad, with the patient and family. The what-ifs are spoken so each individual hears, and tries to comprehend, what it means if the donor heart does not begin to beat or the body rejects the foreign organ. The team is realistic in warning the Ferrallis of the rough road ahead. Yet their passion instills confidence.

It is still scary, the Ferrallis say, but they are ready.

Preparations slow and pre-surgical waiting begins as Steve checks into his room. For three to fours hours, family and friends revisit 4NW, the cardiac wing. Philip and Bethany have driven in from school to be with their dad. At Steve’s urging, Philip leaves to play in a soccer game. He will return for the wait.

Together, the Ferrallis listen for news of the donor heart. Medical staff come and go; transplant team members, nurses, patients stop by to share progress reports, good wishes, hugs. Nurse practitioner Cindy Bither is out of town on this day, but she calls. Though activity swirls all around, time is slowed by the uncertainty.

A Most Generous Gift

At another hospital, a grieving family releases their loved one. Transplanted hearts must come from a person on life support. There is a window of only 12 hours for a heart to be carefully moved from donor to recipient.

At the core of this miracle of new life lies a tragic loss of another life. Thoughts of this family and their munificence are not held lightly on this day, but they are held in check, saved for a time when their enormity of deed may be comprehended. Steve and Sharon wait, their faces wet with tears for the gift of life.

While the Ferrallis are waiting, a search for the perfect heart is underway. The WHC transplant team’s high success rate rests on finding the best match. Behind the team stands the Washington Regional Transplant Consortium, which arranges the transplants. The Consortium first looks for organs with no evidence of disease, then matches donor and recipient.

The first step in the match is blood type. If the recipient’s blood has received foreign antibodies in earlier transfusions, the possibility of rejection increases.

Steve is fortunate: His blood is free of antibodies. Other patients awaiting transplants are not so fortunate, and for them organ matching becomes more complicated.

Size and health of both donor and recipient are additional factors. The donor heart must be similar in size to the heart it will replace in an existing cavity in the chest. Your own heart is not much bigger than your fist. A person in excellent health, as Steve was, will be matched with a heart from someone in similar good health.

August 22: His challenge is maintaining a positive mental outlook until the big day comes. In the meantime we will be prepping for it: installing special water filters, eliminating live plants and dried flowers in the house, cleaning and treating carpets. The heart screening process may mean that two or three opportunities for a transplant pass by. This search is for the perfect heart.

Trust the Dream Team

As the afternoon winds down, Dr. Richard Cooke, team cardiologist, visits. The Ferrallis later learn the significance of his presence. Steve’s “medicine man” has flown back from a business trip in Detroit. In his quiet way, he provides reassurance. He tells Steve and Sharon that there was no way he would miss this one.

It is nearly 6:30pm when the go comes and moments later that Steve raises his arms to the heavens. After the surgery, he will not remember that simple display, but others do.

Steve does remember Dr. Duran, the anesthesiologist, saying he would “get me started.” Leslie Sweet, who spent countless hours training Steve on the pump, holds Steve’s hand. Steve greets Dr. Boyce, the heart transplant surgeon.

The last words Steve remembers are “Are you ready?” He remembers thinking, what choice do I have, then saying, “let’s just do it.” One minute he was on the gurney; the next thing he knew, he was waking up in the intensive care unit.

This transplant team of life-savers begin a surgery that Dr. Cooke will refer to as a “10.” But none of them know that now. Nor do Sharon and Steve nor the friends and family who begin their own vigil

About the transplant team Sharon says, “they make you feel it will all work out.” The wait is filled with shared stories, positive energy, prayer.

This is what the long wait is about. Sharon knows all will come down to the new heart beating inside Steve. This thought is not one she dwells upon. She takes confidence from this caring, compassionate team that literally holds her husband’s life in their hands. Sharon is in awe of “how smart, how skilled” these artists are. She finds the system energizing. She is grateful, even as she waits.

Healing Powers

The minutes move to hours. After five hours, they learn that the LVAD pump is proving a problem. Steve’s good health with the pump is providing irony, as it did when it made him too well to stay at the top of the transplant list. Fully implanted in his body, it is taking longer than normal to remove. The doctors decide to leave in the left drive line, the tubing that runs from inside to out along Steve’s abdomen. It is not an ideal solution. It means a second surgical procedure later. But with time pressing, it is the only option. The time is 11:30pm.

It is 1:45am when they learn that the perfect heart inside Steve is beating in rhythm. In a remarkable feat by two medical teams, the donor has given and Steve received this perfect heart in 152 minutes.

The days that follow bring their own share of challenges. Steve is slowed by a bout with pneumonia. Family and staff are reminded of the fragile state of other organs. Steve’s lungs respond slowly. Infectious disease specialists join the team. After four doses of antibiotics, Steve’s lungs improve. One more hurdle is crossed.

Biopsy shows no signs of rejection. As medications are adjusted, Steve grows stronger. He receives nourishment through a nose tube.

The team and family are feeling mighty good. But for Steve, restless nights and days drift, bumping into one another unfettered by date or time. The bits and pieces of this time that Steve remembers are few when compared to the enormity of his healing. Sharon is in touch with the waiting group through e-mail missives.

September 17: Good evening friends! Amazing … unbelievable … astonishing … a miracle! Call it what you want, but Steve “woke up” today! He is ready to be moved to his old room on 4NW.

Keep the faith. Believe in miracles. You are a witness to this one!

The days, weeks, months of waiting give way to sheer joy. The faith — which, Steve says, “you have to have in any situation like mine,” — brings strength. The dedication of the medical staff has underwritten their faith.

Each day Steve wakes stronger, with a heart beating in rhythm. Less than three weeks after receiving his perfect heart, Steve and Sharon journey home, to the normal life they have dreamed of.

September 26: All is quiet in the Ferralli household at the moment. There was lots of excitement around here earlier. Steve had his third biopsy early this am and by 2:12pm we were quietly checking out of WHC. We arrived home just in time for Steve to rest for a few moments before leaving for Phil’s soccer game. The weather cooperated beautifully so Steve was able to watch the whole game.

Second Opportunity

August 15: Steve got his first bit of transplant info today … 71 prescriptions to start … no flowers, plants, potpourri, etc. in the house … sterilized water only … etc. Another set of adjustments looming …

When you visit Steve Ferralli at home, you are asked to wash your hands. Shoes are lined up just outside the door into the kitchen. There are rituals that become everyday to this family. What would be a slight cold to you or me could set a transplant recipient back.

Steve and Sharon have been told to expect a setback or two. In the two months since his transplant, they have had to deal with hearing that there were some signs of rejection. This came six weeks after surgery, but was corrected by a modification to Steve’s medication.

Steve takes 35 pills each day, eight different medications. For all the good they bring, there have been adjustments. The immunosuppresants, which he will be on all his life, weaken his muscles.

Steve describes these adjustments as “a mental game.” The biopsies every two weeks are no big deal. Steve can drive himself to the Washington Hospital Center now. He is developing his own routine of chores and an occasional trip to Home Depot with his brother-in-law.

Yet he wonders about having an incident. Will he recognize trouble? What will he feel?

Steve will spend some four months recuperating. There will be more adjustments to the medication. He will spend time in physical therapy. Rejection looms in the background. Yet he is returning to the simple life so missed and so desired. Steve longs to be back in the classroom.

November 18: Right now we are in the process of establishing a new “normal” for us. It is not an easy thing since there are so many daily reminders: the huge box of pills by the bed, Steve’s bloated face from the Prednisone and his black-and-blue belly from the shots.

These are the realities of their days. This family has a new life. They are thankful, with understanding that deepens each day. They speak enthusiastically of their experiences. They speak lovingly of people met along the way. Of the visits of transplant recipients to Washington Hospital Center, Sharon says, “there is a natural giddiness among recipients, that they have a second opportunity at life.”

Raise High the Roofbeam

On a cool, cloudy Saturday morning just three weeks after Steve Ferralli’s heart transplant, he joins family and friends at Southern Middle School. He is bright with vitality. It has been four months since many of this crowd gathered here for a blood drive to honor their friend and co-worker. People remark at how wonderful Steve looks.

On a cool, cloudy Saturday morning just three weeks after Steve Ferralli’s heart transplant, he joins family and friends at Southern Middle School. He is bright with vitality. It has been four months since many of this crowd gathered here for a blood drive to honor their friend and co-worker. People remark at how wonderful Steve looks.

In a second show of honor to Steve, an I-beam will be secured within the framework of the school’s progressing renovation. Steve is presented with a white hard hat; white is the color worn by the supervisor on a job. It is inscribed with his name.

The crowd surges toward the beam. There is no stopping them. They are touched by a miracle. The construction crew joins to upright the beam, that proclaims, “Mr. Ferralli Hurry Back” in huge block letters. It is covered with the signatures of students and staff. As one in the crowd finds a pen to add his name and good wishes, others join in the signing.

Then the crew secures the beam with a strong metal cable hanging off the boom of a crane. As folks cheer and clap, it is hoisted to its home two stories above. Two iron workers bolt the joints. The lettering is visible from the street and beyond.

A Journey

A Journey

Steve views his experience as a journey. It is like, he says “going around the world twice.” Tears rim as he considers his family. “You just never think that would happen to your family,” he says.

For the support from so many people, Steve is grateful. He talks of the man from Sante Fe, a kidney transplant recipient, who wrote Steve about a friend of his, a native American, who is living with an LVAD. He wants Steve to understand that he is not alone.

Steve says, “I owe so many people so many things.” He smiles gently as he speaks about all the people “engulfed” in his journey. He feels very special indeed.

In his ninth week out of surgery, Steve says, “it is hard to believe. I was strapped to a battery pack, then — boom! — I am back with a heart.”

Steve accepts his new role as messenger for transplant recipients and those awaiting transplants. It is not just about hearts. Other organs also fail.

He stresses that organ donation is important. It saves lives. The publicity he receives, Steve says, creates a higher awareness about being a donor. He is a witness to the miracle.

Steve also wants to alert people to their vulnerability. Heed your body’s changes, he warns, and go for yearly physicals. They save lives.

During the last month of Steve’s year with a new heart, he begins physical therapy. More good news is that he can decrease his Prednisone, a medication that causes muscle apathy and brings lethargy and weakness.

The roller coaster ride is leveling out, but the Ferrallis know the days to come will be full of challenges. They are returning to, says Steve, “just the simple things, those things that make you go back to what gives you life.”

Tops on his list of the many things he is thankful for is, Steve says, “the family of the donor. It’s like a Christmas list. How could you not put them in there?”

September 9: Your prayers worked, but there’s much more to be done. Please say a special prayer for Steve today. In addition, don’t forget about the donor’s family. They have blessed us with an unexpected gift.

Of dreams, Steve says his “has come true.” He is at home with his family. He can go to Philip and Bethany’s soccer games and he can cheer. In January, he will be back in the classroom. In just one year more, he can mow the lawn. There may even be a family trip to Disney World. “I believe,” says he of his fearful journey, “in finding the silver lining.”